'Death Note' Whitewashing Problem Isn't Just Skin-Deep

Stereotypes inspire Asian-American youths to lash out. What would that have meant in 'Death Note'?

In the months leading up to the new Death Note, I looked at what director Adam Wingard had to say about the whitewashing of his film’s protagonist/anti-hero. As an American adaptation of a popular Japanese horror franchise, the filmmaker argued he made a conscious, yet expected decision to turn Light Yagami into Light Turner, because his movie is “about America.”

His weak explanation for this whitewashing did not impress me or change my mind that Death Note would be a disaster and a missed opportunity. “When moving the setting of Death Note to America we, of course, made the movie about America,” Wingard said on Twitter. “It’s not just a copy and paste situation here.

As an Asian-American, it was genuinely offensive Wingard said that American equals white. But that aside, the whitewashing leaves his Death Note missing a big opportunity. Because Light isn’t an Asian-American, the new Death Note has been deprived of exploring interesting social commentary rarely seen in popular culture: the damage done by haunting “model minority” stereotypes. It’s not the lack of diversity in Hollywood that would have made Asian Light important, it’s that an Asian Light would have turned a Japanese horror into a uniquely American tragedy. And there’s a real-world reason Death Note could have been revelatory.

In 1992, five high school seniors from California were planning to steal from a local computer salesman when they turned on one of their own: 17-year-old Stuart Tay, whom they believed was going to rat them out. On New Year’s Eve, the other four violently beat Tay with baseball bats; when he didn’t die, one of the perpetrators — valedictorian candidate Robert Chan — poured rubbing alcohol down Tay’s throat and taped his mouth shut. Tay died choking on his own vomit in what became known as the “Honor Roll Murder.”

The murder of Stuart Tay gripped headlines, not the least of which because the victim and the perpetrators’ race ran contrary to popular conceptions. Five years before Tay’s murder, TIME ran its infamous cover story, “Those Asian-American Whiz Kids,” which illustrated the academic prowess of Asian diaspora in the west, and Tay and his murders seemed as if they came straight from the magazine. As top students bound for the Ivy Leagues, they believed their clean reputations would be the perfect cover for the robbery.

Leveraging one’s image to carry out darker actions was the same thinking Light Yagami adopted in Tsugumi Ohba’s original Death Note, where Light used his model student image to mask his killing spree. In Death Note, Light is a brilliant but bored high school student who stumbles upon a cursed notebook, the Death Note, enabling him to kill virtually anybody just by writing their names and cause of deaths. Drunk with this power, the sociopathic Light embarks on a crusade to cleanse the world of society’s worst criminals — all while giving valedictorian speeches and earning top marks. No one, Light believed, would ever suspect him.

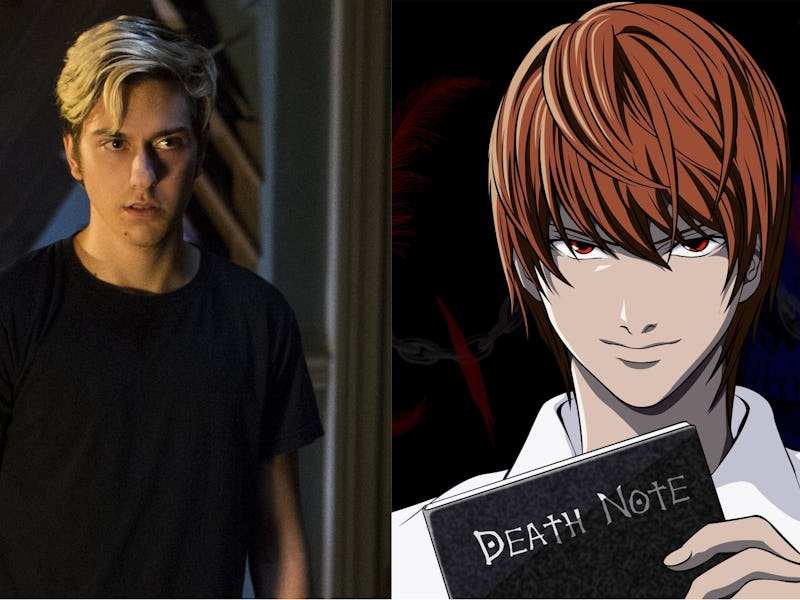

Meanwhile, the new Light Turner (played by Natt Wolf) in Netflix’s Death Note is nothing like his Japanese counterpart. In Wingard’s film, Light is an angsty teen painted with outdated strokes: he’s got frosted tips, a Hot Topic wardrobe, daddy issues, and a crush on Mia (Margaret Qualley), a blase cheerleader who Light impresses with the Death Note. Part Macbeth and part Natural Born Killers, Wingard’s Death Note pursues a different path than its ancestor, which is fine, but whitewashing Light doomed him to a boring limbo. The only time audiences glimpse Light’s intelligence is when he hawks homework for cash. Otherwise, Light is a thundering dumbass and a recycled product of the “white emo guy” archetype we’ve seen before: Donnie Darko, Peter Parker, Scott Pilgrim, Kylo Ren, Joseph Gordon-Levitt in Brick and so much more.

It’s great when directors can interpret foreign material; there’d be no The Magnificent Seven if John Sturges couldn’t reimagine Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai. Yet there is no galaxy where Light Turner is new. But an Asian-American honors student who is a serial killer? What a provocative metaphor for the quiet existential crisis within Asian-American youth that the “Honor Roll Murder” embodied. This isn’t to say our shared cultural anxieties compel us to become murderers. But when there is lashing out, it comes from a very deep and personal space.

A still from 'Better Luck Tomorrow,' Justin Lin's 2002 drama loosely based on the murder of Stuart Tay.

Light Yagami justified his crimes based on his perverse sense of justice. He was brilliant, he was a shining student, so he believed it was his right to divine murder. The new American Light has no twisted moral ground, besides Hey, other people are bad. If Light Yagami was American, he’d hide under the “model minority” image, and for Asian-Americans — like me — that is beyond frustrating.

As a number of data and op-ed pieces show, “good stereotypes” — that Asians are just smarter and law-abiding — are, in fact, horrendously damaging. Not only has the model minority myth driven a wedge between minorities to shame poverty in black communities, and not only do Asian-Americans who fall behind are made invisible, but such expectations eclipse the need for individuals to satisfy themselves. The University of Texas at Austin’s Counseling and Mental Health Center purports that Asian-American students are more likely than whites to report “difficulties with stress, sleep, and feelings of hopelessness,” yet are also “less likely to seek counseling.”

In previous interviews, Death Note creator Tsugumi Ohba said there is no deep meaning other than to live life to the fullest, and that no one has a right to righteous judgment. This affords any storyteller fortunate enough to adapt the story — in this case, Wingard, who’s been blessed with acclaim and reputation through his indie hits The Guest and You’re Next — the freedom to interpret the story however they wish. But as whitewashing has been to blame for Wingard’s mediocre execution, I wonder if his film’s worst problems could have been fixed with a more nuanced casting. There are problems in Death Note beyond the race of its central anti-hero, yet Death Note could have been salvaged had the people in charge saw what lurks beneath one’s skin.

When Chan was arrested for murdering Tay, Chan’s father told the press: “Everything was going perfect. He was a good boy. I don’t understand.”

I can’t help but wonder the provocative story that could have been if the live-action Netflix Death Note had cast Light an Asian-American. It could have been powerful: the new Light using a supernatural notebook to kill people, just because he had nowhere else and nothing else to turn to.

Death Note is streaming now on Netflix.