Neurologist debunks misconceptions about John Fetterman's stroke recovery

The controversy around Fetterman’s recovery from a stroke is medically inaccurate and generally gross.

If you’ve heard about only one Senate race happening this November, there’s a good chance it’s the one between Mehmet Oz and John Fetterman. The celebrity doctor known for hawking questionable diet cures on his infamous TV show is facing Pennsylvania Lt. Governor John Fetterman, who seemed like the obvious favorite for much of the race, despite Oz’s wealth and notoriety.

Fetterman had a stroke in May, taking him off the campaign trail for several months. The Oz campaign saw an opportunity to strike a blow and took it, attempting to put Fetterman’s health front and center in the campaign. Specifically, Oz has harped on Fetterman’s requests for auditory processing aids, like closed captioning for questions asked during a debate or interview. These are sometimes necessary for stroke survivors, especially within the first year of recovery.

The debate over Fetterman’s health reached a fever pitch on Tuesday night when NBC reporter Dasha Burns interviewed Fetterman. Immediately before the interview aired, Burns tweeted that it was “unlike any political interview she’d done,” telling Lester Holt that “because of his stroke, Fetterman’s campaign required closed captioning technology for this interview to essentially read our questions as we asked them. And Lester, in small talk before the interview without captioning, it wasn’t clear he was understanding our conversation.”

Social media exploded over Burns’ statement, with some reporters arguing that during their recent interviews with the candidate, Fetterman experienced no such cognitive confusion and others pushing back against the idea that auditory processing challenges necessarily translate to the cognitive difficulties Burns implied.

Inverse spoke to Pennsylvania neurologist Alan Plotzker about the medical reality behind strokes, recovery, and where Fetterman is in that process.

What is a stroke?

A stroke can occur when something blocks the blood supply to part of the brain or a blood vessel in the brain bursts. An ischemic stroke, like Fetterman had, happens in the former situation: when a blood clot, or other particles, block the blood vessels to the brain. It is the most common kind of stroke.

In Fetterman’s case, doctors said the clot resulted from atrial fibrillation, an abnormal heart rhythm. Atrial fibrillation “can lead to lead to blood clots forming in the heart,” Plotzker tells Inverse. “And then those blood clots kind of get shot up into the brain and can block off a blood vessel. So most strokes happen because a blood vessel gets blocked off one way or another.”

Strokes are so dangerous, Plotzker adds, “because the area [of the brain] right by that blood vessel essentially dies, or is at least damaged, depending on how much blood flow was able to get there.”

How might a stroke impair someone’s auditory processing?

Strokes can have a wide range of effects, Plotzker says, “because it really depends on what area of the brain is affected.”

Plotzker doesn’t know exactly what part of Fetterman’s brain was affected by the stroke but guesses that it was an area involved with language processing, rather than auditory areas. He bases that guess on two factors. “First, strokes on one side of the brain don’t usually impair hearing specifically, and second, in addition to auditory processing, he also has some issues with speech production, which is not uncommon with strokes that affect some of the language areas,” he says.

In medical terms, Fetterman has “some degree of aphasia,” Plotzker says, which simply means “some language deficits.”

In contrast to people who have a large stroke affecting the left hemisphere of the brain and develop global aphasia, in which they can’t speak at all or understand language, other people may have deficits only with certain aspects of language, according to Plotzker. Fetterman has been quite open about those deficits.

In his interview with Burns on Tuesday night, he told her, “I sometimes will hear things in a way that’s not perfectly clear. So I use captioning so I’m able to see what you’re saying on the captioning...And every now and then, I’ll miss a word. Every now and then. Or sometimes I’ll maybe mush two words together. But as long as I have captioning, I’m able to understand exactly what’s being asked.”

This is all entirely normal, according to Plotzker. “Neither a language nor an auditory processing problem necessarily indicates an underlying problem with the thinking [the stroke survivor] does,” he says. “Unfortunately, it’s very rare for people to understand that.”

When doctors assess a stroke survivor's faculties, their tests are “quite practical,” Plotzker says. “It’s basically ‘can the person do X?’”

So when it’s clear that Fetterman can understand what he sees visually but has trouble hearing it. “He clearly understands [the question] when it's in the appropriate format for him. That ability is clearly still there,” Plotzker explains.

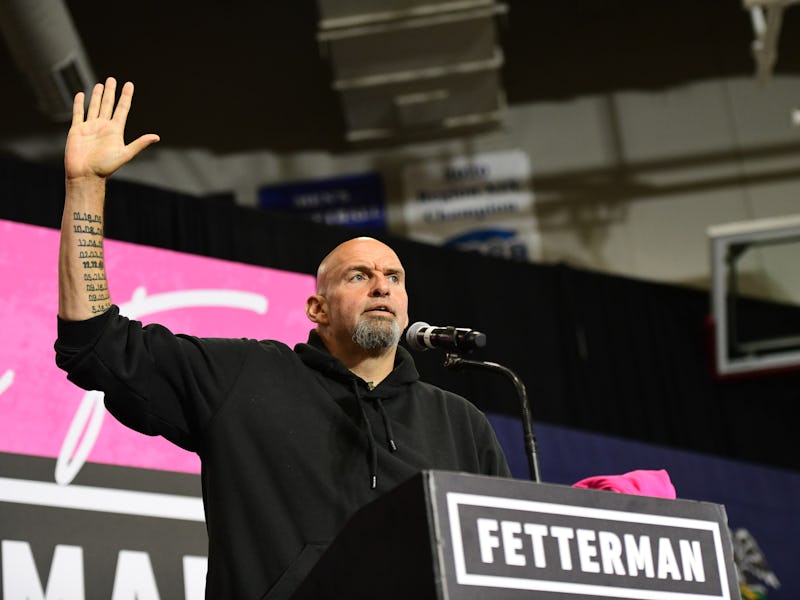

Fetterman faces celebrity doctor Mehmet Oz in a race for U.S. Senate.

In other words, if Fetterman’s critical thinking abilities were impaired, he wouldn’t be able to coherently answer questions in any format; the impairment wouldn’t be specific to one type of communication.

“Multiple people that have interviewed him using that kind of assistive technology have found him to be totally coherent and fine,” Plotzker notes.

This makes characterizations like those made by Chris Matthews Wednesday morning so abhorrent and simply false. On Morning Joe, Matthews characterized Fetterman as “a guy who cannot answer the question because he has to look at the monitor."

Such characterizations conflate Fetterman’s ability to understand the question in one format with his ability to answer it in any form.

A stroke survivor’s road to recovery

Underscoring the whole controversy is the relatively short time it’s been since Fetterman’s stroke.

Recovering language facility following a stroke is slower than regaining muscle or physical strength. While strength can recover in months or weeks, with language, “people can continue to improve six months or even a year or two out. So the deficits he has now are not necessarily deficits that he's going to have forever,” Plotzker explains.

Still, Plotzker says of Fetterman, “Even with the deficits that he has right now, it seems that he's able to be able to communicate the things he needs to,” adding that Illinois Senator Mark Kirk had a stroke while serving in the senate and was able to return to his duties. Additionally, he says, Chris Van Hollen and Ben Ray Luján are both current senators who had strokes and seem to be doing their jobs just fine.

Ultimately, the controversy has broader implications than a high-profile Senate race: specifically, how we talk about and understand people with disabilities.

“People having strokes are very common. And lots of people who have had strokes will have some form of aphasia,” Plotzker says. “Even more commonly, people will have hearing issues but can’t afford hearing aids. So the perception that those people can’t function at a high level is certainly harmful to them as well as to the people who would benefit from the person getting the job done.”