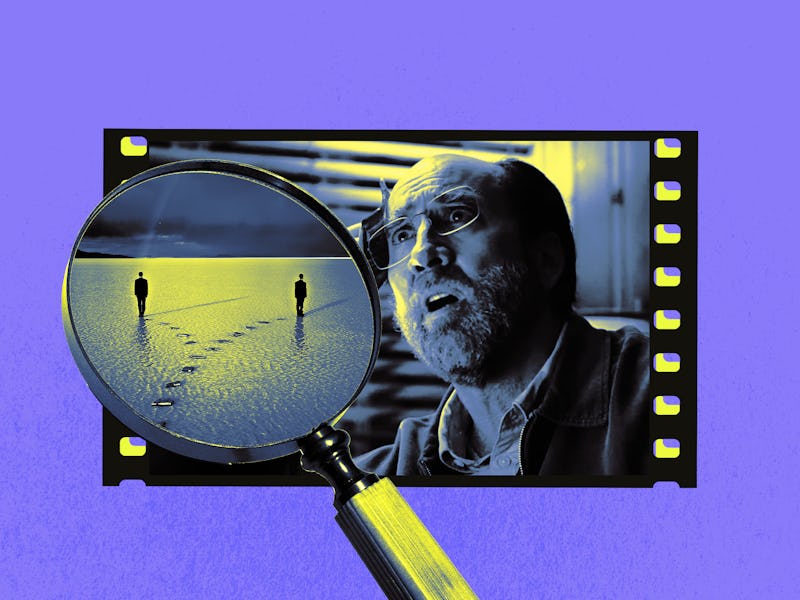

Nicolas Cage's Trippy New Sci-Fi Movie Uncovers a Weird Field of Dream Science

Dream Scenario is just a dream, but there’s real psychology at its core.

Dreaming about people we know personally can be harrowing. While they may show up looking like the friend or parent we’re familiar with, they may carry an aura of someone completely different, representing two entities at once. And if you found out someone else independently dreamed of that same person on the very same night? Spooky.

In indie film company A24’s new movie Dream Scenario, that concept is taken to the extreme when people far and wide begin seeing the same man in their dreams. The man, a schlubby evolutionary biology professor named Paul Matthews (portrayed by Nicolas Cage), must contend with becoming a shut-eye icon when his students, colleagues, family, and strangers start seeing him wander through their dreamscapes.

As Matthews tells his young daughter, while trying to make sense of this madness, dreams are “hallucinations” that the brain makes while asleep as part of its “housekeeping.” This description is consistent with what scientists tell us about dreams, that it’s the brain’s way of processing wayward thoughts and images. What they — and Matthews — don’t fully understand is the phenomenon of shared dreams.

Shared dreams haven't been observed or studied at Dream Scenario’s imagined scale before. But, the phenomenon — defined as dreams that at least two people have with similar contents — is of great interest to psychologists. The research available demonstrates what conditions may facilitate these mutual flights of fancy.

Dream a little dream of me

By definition, dreams are “mental content that occurs during sleep,” says Patrick McNamara, a neurology professor at Boston University. Shared dreams, he says, typically crop up between people who have some sort of relationship. “That person is emotionally important to the dreamer.” He adds that the dreamer might have a genetic or emotional attachment to this person.

Deirdre Barrett, a lecturer on psychology at Harvard University and author of The Committee of Sleep, tells Inverse that one hypothesis behind dream function makes it more likely that shared dreams will occur on a personal level. The continuity hypothesis posits that dreams simply follow similar lines of thought as during waking hours. In other words, our dreams are just continuations of our thoughts from the day, so of course, we’re prone to dream about the people we see or think about every day.

As such, it’s reasonable that shared dreams might crop up between people who see each other every day, like couples. In a 2017 article called Mutual Dreaming, published in the 2019 anthology Dreams: Understanding Biology, Psychology, and Culture [volume 1], McNamara and his co-authors review previous studies of shared dreams. The article points to a 1994 study of one couple who had 153 recorded dreams over 10 weeks, 13 of which were shared. That number may not seem immediately impressive, but the degree to which the shared dreams overlapped was surprising.

In these 13 shared dreams, on average, a whopping 39 percent of the content overlapped, while unshared dreams only matched 5 percent. This figure indicates that “such overlap cannot be a result of chance due to the low frequency at which such items occurred.” In other words, it’s no mere coincidence that these mutual dreams jumped so much in shared content. The authors of the 1994 article also “advocate that a benefit of mutual dreaming is to help strengthen emotional ties between people that desire to develop a relationship.” With this in mind, it’s plausible that Dream Scenario’s protagonist would appear in his daughter’s dreams; it might even improve his relationship with them. But in the whole world’s dreams? Far less likely.

What does dreaming of someone tell us about ourselves?

Making a shared dream

The lore of shared dreams extends far beyond Nicolas Cage. Nightmare on Elm Street explores the horrors of mutual dreaming (and also nightmares coming to life), and McNamara notes that many cultures and religions ascribe prophetic powers to dreams. Knowing that shared dreams can simply come from what you choose to think about during the day means it may be possible to create them.

Barrett says that folks interested in dreams, like members of the International Association for the Study of Dreams, might sometimes try to “meet up” in dreams. They’ll agree on a location for everyone to envision, and as they sleep individually, they’ll concentrate on visualizing this place with all their friends. Barrett explains that this is less of a literal hang session in dreamland and more of an exercise for dream enthusiasts to practice to hone their skills. Some of this theory shows up in the film as a darkly funny Gen Z “dreamfluencer” company, which preaches dream-sharing practices and uses it as a way to advertise.

Dreams, shared or not, probably tell you more about your own mind than the world around you. If dreams are simply a reflection or expression of your thoughts and feelings, it’s another window into how you experience the world.

Still, if you dream of Nicolas Cage tonight, don’t be shocked.