Animal evolution explains why social distancing is so difficult

"Challenging social environments can directly affect health and well-being."

At a time when most socializing is happening remotely, new research points to just how important social connections are to human health and longevity.

An analysis of long-term studies on social mammals — both humans and other animals — revealed that being social is one of the strongest factors determining morbidity and mortality. Morbidity is one's level of health and well-being while mortality is one's risk of death.

The review study was published on Thursday in the journal Science.

"In both humans and other social animals, measures of social integration and social support have been shown to predict better health and/or longer lifespans," study co-author Jenny Tung, a biology professor at Duke University, tells Inverse.

In some cases, Tung explains, social status has the same effect — even within some non-human mammal populations.

"These findings suggest that evolving highly social lifestyles, as we and many other species have done, generates strong dependencies between successfully navigating social relationships and how well our bodies do," Tung says.

The research team examined previously conducted animal studies in which only the social environment was changed. In turn, research indicates that this change can sometimes drive chronic stress, increased inflammation, tumor-like conditions, and symptoms similar to heart disease.

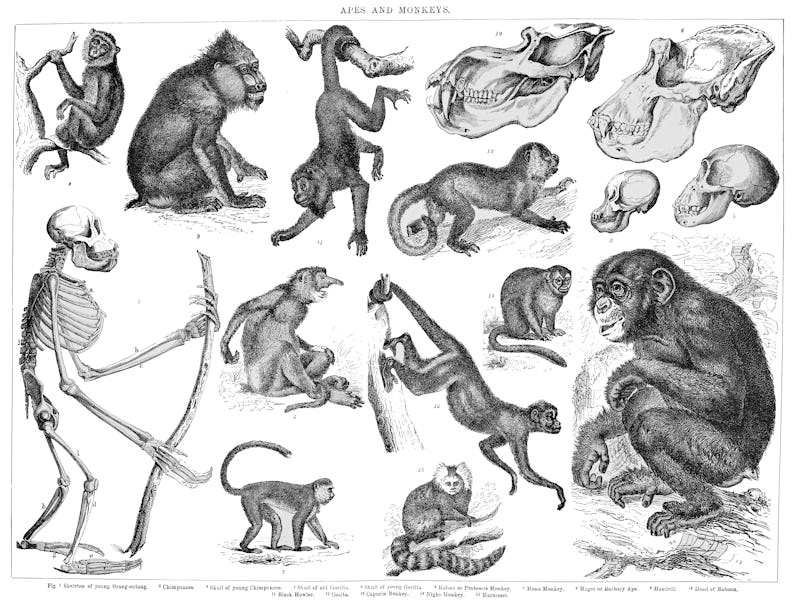

Macaques, blue monkeys, bottlenose dolphins, orcas, bighorn sheep, wild horses, rock hyraxes — studies indicate that all of these animals are more likely to survive when they are socially integrated.

"This kind of work helps highlight that challenging social environments can directly affect health and well-being," Tung says.

Considering most of the world is still operating from a distance, this research brings up questions about what it means for humans (and maybe some animals) to be socially isolated from one another.

Right now, minimizing the Covid-19 pandemic is paramount — "so from a very immediate perspective, it is an essential strategy for improving population health," Tung says.

But negative reactions to social distancing, and how it affects people psychologically, could be explained by the inherent knowledge that being social benefits health.

"I think the difficulty of being able to maintain social distancing policies speaks to our strong motivation to stay in social contact and reinforce our relationships with others," Tung says.

Co-author Noah Snyder-Mackler, a researcher at Arizona State University, adds that the most severe cases of Covid-19 are in people with pre-existing health conditions — "which themselves exhibit a social gradient that is not unique to humans."

Socialization is known to be a factor that influences pre-existing conditions. Studies indicate that people who are more socially integrated have lower rates of stroke, asthma, heart disease, and bronchitis. Chronic conditions are known to make Covid-19 worse.

"This means that the current pandemic is amplifying health gradients that already exist in society, which emphasizes the need for us to implement policies and solutions that eliminate (or at least mitigate) these gradients, Snyder-Mackler tells Inverse.

Baboons sacrifice rest, not socializing, when environmental conditions are tough.

For some, disrupting social routines can cause changes in sleep, worsening of mental and chronic health conditions, and changes in substance use. One recent survey found that 40 percent of Americans are anxious about the coronavirus.

Motivations to stay in contact with others are partly due to evolutionary history: Humans have been a social history for a very long time. Tung points to a separate piece of research by study co-author Susan Alberts, whose baboon studies show that the primates will prioritize socializing, even when environmental conditions are difficult. When rainfall is scarce, the baboons have to spend more time foraging – but rather than minimize their socializing, the primates spend less time resting.

"We often tend to think of our social relationships as something we pursue in our 'free' time," Tung says, "but they may not be so discretionary after all."

Abstract: The social environment, both in early life and adulthood, is one of the strongest predictors of morbidity and mortality risk in humans. Evidence from long-term studies of other social mammals indicates that this relationship is similar across many species. In addition, experimental studies show that social interactions can causally alter animal physiology, disease risk, and life span itself. These findings highlight the importance of the social environment to health and mortality as well as Darwinian fitness—outcomes of interest to social scientists and biologists alike. They thus emphasize the utility of cross-species analysis for understanding the predictors of, and mechanisms underlying, social gradients in health.

This article was originally published on