Why do people have lucid dreams? Study questions the limits of consciousness

“Our experimental goal is akin to finding a way to talk with an astronaut who is on another world.”

The words came like the voice of God, cutting through the hubbub of the party around him.

From somewhere beyond his perception, a voice asked: “Do you speak Spanish?” He hesitated. He had expected the questions to come — but he did not know how to answer this one.

Eventually, he responded to the voice: “No.” He had a good grasp of Spanish, but he wasn’t fluent. The voice asked some more questions, and the young man answered, yes or no.

And then he woke up.

This 20-year-old biology student, identified only as “AC,” was one of 36 participants in a proof-of-concept study investigating whether it is possible to have a real-time, two-way conversation between a researcher and an asleep dreamer. And along with five other participants, AC’s experience reveals the answer appears to be yes.

AC is in some ways a special case — he has narcolepsy, a sleep disorder which causes people to fall asleep both often and spontaneously throughout their day. Narcoleptics also tend to be lucid dreamers — essentially, people who know they are dreaming and can interact with, or even fundamentally alter, their dreams as they occur.

But you do not need to be narcoleptic to have lucid dreams. I know this because I have them too.

What’s new — The study, published Thursday in the journal Current Biology, offers a novel paradigm to study lucid dreams as they occur. It shows a real-time, two-way dialogue between dreamer and researcher, in a research setting, is possible.

But the study goes further: The four labs involved tested the method by asking participants complex questions — both in the form of yes/no questions, as were asked of AC, and in the form of mathematical equations, like “What is 8 minus 2?” They also looked at whether participants could perceive external stimuli, like tones and lights, within their dreams.

“This kind of experiment can give you real-time information, which is very precious from a dreamer’s perspective,” Delphine Oudiette, an Inserm Researcher at the Paris Brain Institute and co-author on the study, tells Inverse. She is also a researcher in the Sleep Department of Pitié-Salpétrière Hospital in Paris.

The higher cognitive skills and problem solving dreamers displayed during interactions with awake researchers not only offers a new and perhaps more precise way to study lucid dreams as they occur, but it also opens a more interesting door: Is it possible to tap into a person’s creative abilities in ways they would be unable to do during wakefulness while they dream?

Imagine, Oudiette explains, you are trying to solve a problem while awake and you spend a week or more on it. But then, you try to solve the same problem in your dream.

“Your brain is capable of constructing a completely accurate virtual reality.”

“We could design cognitive tasks that could be performed during dreams in the same way as we do when studying cognitive functions during wakefulness,” she says.

“That would be a really interesting future direction of this methodology,” Benjamin Baird tells Inverse. Baird is a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of Wisconsin, Madison who studies lucid dreams, but was not involved in this study. He also has lucid dreams himself.

Oudiette goes further: If a person can perceive and react to their world while in a state of REM sleep as if awake, where, then, do the limits between conscious wakefulness, and the unconscious, lie?

“Everybody has a theory of why dreams happen, and what they can tell us about ourselves,” Oudiette says. “But we still don't have the answer.”

Lucid dreams, Baird says, do offer the promise of an answer to this very human enigma, however.

What are lucid dreams?

Lucid dreams are essentially dreams in which the dreamer is lucid — that is, aware they are in a dream, able to perceive their surroundings, and, at least in some cases, able to direct the narrative of the dream and able to communicate with the outside, awake world (as in this study).

A person can experience lucid dreams naturally (like me), or as a consequence of a sleep disorder, like AC. According to the still-emerging body of research on lucid dreaming, it is also possible to train oneself to have lucid dreams, or even stimulate lucid dreaming using pharmacological interventions.

The film Inception explored the idea of lucid dreams, and referenced the reality-checking method, which in the film took the form of checking a spinning top.

One of the most popular techniques out there is the reality-checking method. In this practice, you train yourself to check your reality — whether it is to look in a mirror, or concentrate on a body part, for example — while awake. Eventually, you will do the same in a dream. This can induce lucid dreaming, so the theory goes. For those trying to imagine how to do this, it is basically the premise behind Inception’s spinning top.

Another technique is the Mnemonic Induction Lucid Dream method. In this practice, you basically play at having a lucid dream, imagining you are lucid dreaming, and setting an intention to engage in a lucid dream the next time you have a dream along the same narrative lines. According to some research, this is best done with a regime of multiple wakings. In other words, you wake yourself up at 1 a.m., 4 a.m., and so on, and repeat your intention each time.

For myself, lucid dreams seem to be the result of repetitive nightmares. For a reason I can’t explain, my brain trained itself to recognize when I am dreaming an all-too-familiar dream and make me aware of it. Generally, these moments of lucidity come in the form of an inner monologue, like I am talking to myself, telling me to beware, I’m in that dream, and I need to get out of it ASAP. I’ve gotten pretty good at paying attention (and generally waking myself up in the process), if I do say so myself.

Baird doesn’t use his abilities to stop dreams, he tells me. Rather, he says his favorite thing to do in a lucid dream is to explore his environment using his senses, no matter how mundane (or strange) it may be.

“Seeing a strawberry, seeing the redness of the strawberry, tasting the strawberry, how it tastes like a strawberry, smelling the strawberry,” he explains.

“That shows that a fully mature brain is capable of constructing all five sensory modalities with full realism and vividness, completely disconnected from the environment,” Baird says. “So your brain is capable of constructing a completely accurate virtual reality, independently of the external world.”

John Henry Fuseli's 'The Nightmare' captures the terror of nightmares for dreamers, like me.

Here’s the background — Past work on lucid dreaming has tracked dreamers’ brain activity in sleep, and, after people have woken up, matched these patterns of activity to the self-reports from the dreamers. In other studies, dreamers have used specific eye signals to indicate they are in a dream.

Researchers have also given dreamers external stimuli, like a flashing light, while they sleep, and asked them after they woke whether they perceived the stimuli in the dream.

But ultimately, relying on self-reports, even when synced up to brain activity read-outs after the fact, is a major limitation for the field, Oudiette says.

“Basically, we study a memory,” she explains. “And the memory can be distorted.”

The human brain also has a tendency to ‘fill in the gaps’ of memory fragments, and attribute meaning and symbolism to events in order to make sense of them — all of which corrupt the self-report. Even syncing up dream activity with brain activity can be difficult, she says, because it is hard to spot in the data when a specific incident in a dream began, and when it ended.

Instead, Oudiette and her colleagues’ study proposes a different paradigm:

“Our experimental goal is akin to finding a way to talk with an astronaut who is on another world, but in this case the world is entirely fabricated on the basis of memories stored in the brain.”

What they did — This study is a little unusual, in that it involves four teams based in Germany, the U.S., the Netherlands, and France, and each uses four slightly different protocols to test the premise that real-time, two-way communication in lucid dreams is possible. Oudiette was part of the French arm of the study.

AC, for example, was the sole participant involved in the French arm of the study, and, as noted above, a frequent lucid dreamer. The American group, meanwhile, involved 22 participants, most of whom were students aged between 18 and 33 years old, and who claimed to often remember their dreams but were not necessarily lucid dreamers. The Dutch experiment involved 13 people who had similar dream recollections to the American participants, aged between 19 and 37 years old, and the German group involved ten people, all of whom were trained lucid dreamers with a rich history of lucid dreaming.

From these participants, the study’s final sample size includes data from 36 participants, only six of whom were confirmed to have a lucid dream during the course of the study and were also able to engage in the two-way dialogue with researchers. Interestingly, these six hail from all four groups in the study.

According to study co-author and professor of Psychology and James Padilla Chair in Arts & Sciences at Northwestern University Ken Paller, the initial analysis suggests there is nothing special about those participants who succeeded in having a conversation while in their dream state, and those who did not. This suggests this kind of dialogue is possible regardless of your prior experience with lucid dreaming.

Each participant was hooked up to a polysomnography machine while they took naps — essentially, these are machines which track electric activity in the brain via electrodes placed on the scalp, and also facial movements, including eye and mouth movements, via electrodes placed on the face. The machines tell researchers when the wearer has slipped into the sleep stage known as REM sleep — this usually happens after 90 minutes of sleep time and is the stage of sleep in which your body remains still but your mind transports you to the land of dreaming.

During this sleep state, your brain activity reflects patterns seen in wakefulness. Before they slept, participants were told to expect questions and other stimuli from experimenters in their dreams, and how to respond. Importantly, the participants were not told which questions they would be asked ahead of time, so the dialogue would be novel.

Participants were then asked while asleep to signal if they were in a lucid dream by moving their eyes in a specific pattern — left-right, left-right, left-right — or a facial signal. To be clear, these sorts of facial expressions are quite different to those produced in REM sleep spontaneously, so Oudiette says she and her colleagues could be confident these were true responses to researchers’ questions.

“We know maybe more about the planets and space.”

Once a lucid dream was established, the researchers then went on to ask specific questions of their participants. That’s why AC heard the ‘voice of God’ asking whether or not he could speak Spanish, for example. For other participants, the questions and stimuli came in other forms, including in the form of objects, or other people in the dream.

“Sometimes it's integrated, and sometimes it's not,” Oudiette explains. For one participant, for example, he experienced a finger-tapping stimuli as goblins with strange fingers attacking him — but he still managed to disassociate himself from the dream and answer the experimenters’ questions.

Whether it was details about their personal life or basic arithmetic, the participants each had just 30 seconds to respond to be counted as a true answer to the question asked, Oudiette says.

“You have to understand the problems, and then calculate in your mind, and then emit the response,” she explains.”It's complex enough to say that it's communication. But easy enough to get a signal, you know?”

I’ve never engaged in a dream study like this, but I have had the experience of answering a person’s questions during sleep — although, in my case, my responses were verbal. They made sense, apparently — to a point. Oudiette says I may actually have been sleepwalking, rather than engaging in a true dialogue, as in this study. I could also have been sleep-talking, but that is poorly studied. If sleepwalking, my motor cortex may have showed activity similar to that of wakefulness, she speculates — which brings us to another question this study design could go some way to solving.

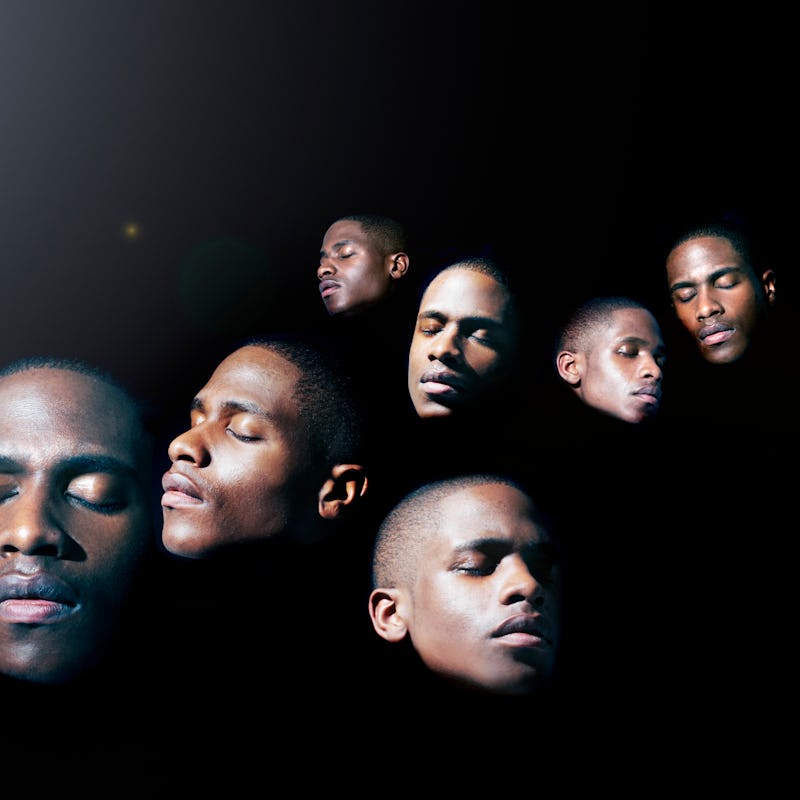

Lucid dreaming may enable people to tap into creative abilities, a new study suggests.

Why it matters — One of the most important implications of this study is it shows lucid dreamers can engage in complex problem solving and perhaps even creative thought.

If a person can answer the problem of 8 minus 2 correctly in sleep, then perhaps they could be guided to answer increasingly complicated computational problems.

Further, if AC can reason he can’t honestly answer the question of whether he speaks Spanish with “Yes,” because he is pretty good but not fluent in Spanish, then a line of other yes/no questions could ostensibly take him and others through a very different creative process, Oudiette says. This was not the purpose of this study — the other questions AC was asked, like whether he likes chocolate, aren’t what you and I would judge to be overtly creative musings, for example. But the fact he could answer is enough to signal a deeper conversation may be possible.

Baird suggests the study’s findings also open up new possibilities for people like me, too. In one of the repetitive nightmares I experience, I am being chased. What if I didn’t stop the dream, but instead turned around and faced my pursuer? And what if I could then tell a researcher or clinician about this interaction as it happens? Perhaps, he suggests, I would get some closure.

But beyond providing me with answers, the study design could also help researchers investigate an emerging idea in sleep research — the idea of local sleep and wakefulness. Essentially, this is an idea that parts of the brain may be connected during sleep, suggesting the boundaries between what we typically define as consciousness and unconsciousness may be far more blurry than we know.

“The classic definition of sleep is that we are disconnected from the external environment,” Baird says. “And so here we have a case where people are in clinically defined, polysomnography defined sleep, and yet they're connected, they are able to perceive something from the external environment and respond to it.”

What’s next — Before these greater questions can be tackled, Oudiette says her lab plans to tap into their clinic of narcolepsy patients to do a larger study validating their initial results in at least 20 participants. After the study is repeated in Oudiette’s lab and elsewhere, then they will be able to do further experiments, such as delve into the brain activity data collected while participants experience the same stimuli awake and asleep. In these data may be specific signatures which reveal how sleep manifests in the brain.

Eventually, she says, the protocol can then be used to ask the more complex, creative questions.

“We can imagine a lot of experiments,” Oudiette says.

Baird says studies like this offer not only a novel method, but also represent a sea change in dream and sleep research more broadly.

“For a long, long time, there was a kind of moratorium on consciousness research at all,” he says. “Now, it's really seen as one of the major outstanding problems of science.”

“Studying the differences in what's going on in terms of neural processing, when people are actively perceiving that information versus when they're not, can actually teach us something about the neural mechanisms of connection versus disconnection of the brain more generally,” he says.

Oudiette compares her work to the explorers of old — our unconscious mind is a frontier we all hold within.

“The fact that we cannot even know what a dream is, really its kind of puzzling from a scientist’s perspective,” she says.

“We know maybe more about the planets and space, which is so far from us."

Abstract: Dreams take us to a different reality, a hallucinatory world that feels as real as any waking experience. These often-bizarre episodes are emblematic of human sleep but have yet to be adequately explained. Retrospective dream reports are subject to distortion and forgetting, presenting a fundamental challenge for neuroscientific studies of dreaming. Here we show that individuals who are asleep and in the midst of a lucid dream (aware of the fact that they are currently dreaming) can perceive questions from an experimenter and provide answers using electrophysiological signals. We implemented our procedures for two-way communication during polysomnographically verified rapid-eye-movement (REM) sleep in 36 individuals. Some had minimal prior experience with lucid dreaming, others were frequent lucid dreamers, and one was a patient with narcolepsy who had frequent lucid dreams. During REM sleep, these individuals exhibited various capabilities, including performing veridical perceptual analysis of novel information, maintaining information in working memory, computing simple answers, and expressing volitional replies. Their responses included distinctive eye movements and selective facial muscle contractions, constituting correctly answered questions on 29 occasions across 6 of the individuals tested. These repeated observations of interactive dreaming, documented by four independent laboratory groups, demonstrate that phenomenological and cognitive characteristics of dreaming can be interrogated in real time. This relatively unexplored communication channel can enable a variety of practical applications and a new strategy for the empirical exploration of dreams.

This article was originally published on