PFAS: Your home is full of potentially harmful "forever chemicals" — here's what you need to know

Four experts explain what PFAS are found in, how you can become contaminated, and how they may affect your health.

Potentially toxic chemicals called PFAS are found practically everywhere — your home included. But just how dangerous are these chemicals, and how might they affect your health?

In a study published Tuesday in the journal International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, researchers examined the links between 26 PFAS and cancer, all were found to have at least one carcinogenic trait. To understand the links between these chemicals and our health, four experts weigh in on how abundant these chemicals really are and what — if anything — they may do to our bodies.

PFAS stands for perfluorooctanesulfonic acid and perfluorooctanoic acid. These so-called "forever chemicals" are used extensively in manufacturing, and can be found in hundreds of everyday products from carpets and pans to pizza because they make things waterproof and stain-proof.

They earned the moniker "forever chemicals" because they don't degrade readily in the environment, and they linger in our bodies for extensive periods of time.

There are 5,000 types of PFAS, and scientists don’t really know to what extent each may mean trouble. But the evidence suggests at least some of these forever chemicals may have negative consequences for our health. Studies link PFAS to a large range of health issues, including weakened immunity, fertility problems, and even cancer.

What are PFAS chemicals found in?

PFAS are almost ubiquitous. “We're exposed through lots of different routes unfortunately,” Anna Reade, staff scientist at the environmental advocacy group Natural Resources Defense Council, tells Inverse.

“PFAS are widely used and they have been used for decades for all kinds of consumer products and industrial uses, which is one of the reasons why not only do they not go away, but because we've used them so widely, they're everywhere,” Reade says.

PFAS are present in many consumer products, including lots of food packaging. One of the most-common places you will find PFAS are in nonstick items, experts say, but the kitchen is certainly not the only place you find them. You could even be walking on PFAS right now.

“You can think of anything that is like nonstick pans or water resistant clothing, carpets, rugs,” Reade says. A 2018 study by researchers at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam found PFAS in five out of 12 carpet products tested.

“There are studies that show that for a child, 40 to 60 percent of their exposure came from crawling around on PFAS contaminated carpets,” Reade says.

"[PFAS are] another reason to eat more home-cooked meals and more fresh foods."

“Or greaseproof food packaging,” Reade says.

In fact, fast food packaging tends to be full of PFAS chemicals. Among the top offenders are microwaveable popcorn bags, which are coated in these forever chemicals to make them grease resistant. And you are likely eating them as a result.

“You heat them up at a high level, that PFAS is going to come off onto that popcorn and increase your exposure to those chemicals,” Reade says. This is known as leeching.

Are PFAS found in food?

The short answer is yes, the experts say.

In a 2017 study conducted by the Silent Spring Institute, another advocacy organization, researchers show that people who eat more home-cooked meals tend to have lower PFAS levels than those who ate pre-packaged food.

“If we need another reason to eat more home cooked meals and more fresh foods, [this can also be] a reason to eat healthier,” Laurel Schaider, a research scientist at the Silent Spring Institute, tells Inverse.

As for the popcorn, heat the kernels up on the stove, or use a plain brown paper bag to zap it in the microwave instead, she says.

PFAS in microwave popcorn bags could end up in your body, research suggests.

But even away from pre-packaged and fast food, we still aren't free from exposure to PFAS in food.

“Plants and animals that we eat can absorb PFAS from the soil or the water where they're grown,” Schaider says.

PFAS levels build up in our food web, and are likely present in the meat or salad you’re preparing for lunch, too, she says.

The more PFAS travel up the food web, the more the levels of contamination increase — a process called biomagnification.

“If they're present in lower organisms on a food web, then they'll end up at higher concentrations in, like, fish that eat other fish,” Carrie McDonough, a chemical oceanographer from Stony Brook University tells Inverse.

Specific populations may be disproportionately affected by food-borne PFAS, a 2019 study suggests. Ultimately, cooking your food from basic ingredients instead of just microwaving a packet or eating take out may help lessen your exposure, the experts suggest.

Are PFAS in drinking water?

“Not everybody's water is contaminated, but there are a lot of communities across the country that have really high levels of PFAS contamination in their water,” Reade says. For some, that means chronic levels of exposure to PFAS just by virtue of drinking water every day.

“The highest levels of water contamination have been linked to certain types of sources,” Schaider says.

“One very common source of water contamination is a certain class of firefighting foams: these are used to put out fuel fires. They show up in the environment close to military bases, airports and other fire training areas because they're often used for training for these types of fires. Or for instance, if a plane catches on fire.”

There can also be higher levels of PFAS-contaminated drinking water near industries where these chemicals are manufactured.

For example, in Minnesota, West Virginia, or North Carolina, near three DuPont plants, there appear to be higher-than-expected levels of PFAS drinking water, Schaider says. The same is true in other industrial areas of the country, she says.

Why do PFAS last forever?

Once they are in the environment (or our bodies), PFAS chemicals do not easily break down.

“This is actually true of a lot of persistent pollutants: they're often designed to be very stable for the applications that they're used in,” McDonough says. This is by virtue of their design: For products like a non-stick pan to work the way we want them to, then they have to be able to last.

“But that means that when they get out into the environment, they can also be very stable," she says.

Once they are out in an environment, they can move quickly, Reade says.

“Once they're released, their contamination is very hard to contain. They often build up and bioaccumulate,” she says.

"Their structure kind of mimics what a fatty acid looks like.”

The reason why PFAS are super-resistant to wear and tear is because of their molecular structure. The chemicals have many carbon fluorine bonds — some of the strongest chemical bonds possible.

In the human body, their molecular structure also makes them very resistant to being broken down by our own waste disposal system.

“One of the interesting things about PFAS is their structure kind of mimics what a fatty acid looks like,” McDonough says.

“So they actually can associate with the transporter proteins in your blood. That's different than a lot of other types of contaminants that would usually be attracted to your fatty tissue,” she says.

“So there's a portion that will stay in your blood for quite a long time.”

This can be for up to five to ten years.

How do PFAS affect your health?

According to Reade, 98-99 percent of us have PFAS in our blood. So we are pretty much all exposed.

“They interact with our body in a lot of different ways. And they look somewhat similar to certain key protein molecules within our bodies so they can interfere with our ability to function how we should,” Reade says.

Infants may be at particularly high risk of exposure, the experts say. They can pass through the placenta, from the mom to the child, and also through breast milk. A 2016 study shows that prenatal transfer through the placenta and postnatal transfer through breastfeeding are among the main contamination sources for toddlers for some PFAS chemicals (PFOS, PFOA, PFHxS and PFHpS).

According to Reade, PFAS contamination may affect children's immune systems, even to the extent that vaccinations against common childhood diseases may be less effective as a result.

“Scientists are still learning about the levels of exposure that might be associated with harmful health effects."

A 2017 review of 26 studies found evidence of positive associations between PFAS and immunity problems (including vaccine response, especially the tetanus vaccine, and asthma in children), renal function, and unusual onset of puberty in some children.

“Scientists are still learning about the levels of exposure that might be associated with harmful health effects,” Schraider says.

“PFAS exposure has been linked to effects on the immune system, particularly the immune systems of children, effects on the thyroid, increased cholesterol, effects on the kidney, and even certain types of cancer,” she says.

A 10-year longitudinal study of over 750 Korean adults published in 2018 links cholesterol levels and exposure to PFAS. There are also data to suggest PFAS exposure among female firefighters may be linked to instances of breast cancer among female firefighters. But the evidence linking PFAS exposure and breast cancer is not clear cut: For example, there does not seem to be the same levels of problems for teachers exposed to PFAS in the course of their work, albeit at lower levels.

In the new research published on Tuesday, scientists find significant evidence of a link to cancer, although the analysis only considered 26 of the thousands of PFAS out there.

“Our research has shown that PFAS impact biological functions linked to an increased risk of cancer,” says Alexis Temkin, a lead scientist on the study, said in a statement accompanying the research.

More research is needed to fully understand the scope of the harm these chemicals can cause, the United States' Centers for Disease Control says.

How toxic are PFAS?

Ian Musgrave, a toxicologist from the University of Adelaide, tells Inverse that everyday levels of exposure aren’t actually that big of a threat to health. We should be careful, but not particularly worried about PFAS chemicals’ impact on our bodies, he says.

“Standard exposure may not do very much at all.”

Most studies of PFAS' effects are in rats. But rats have far more sensitive receptors to PFAS than do humans, he says.

“About a thousand times more. So they respond a lot more dramatically than humans do,” Musgrave says.

Much of PFAS research has focused on biomarkers — biological signatures that may predict a person's future health, like whether they are going to have a heart attack. In the case of these kinds of events, the evidence that PFAS might have to do with them is murky, Musgrave says.

“If we look at the cardiovascular effects, even in highly exposed populations, we don't see consistent changes in plasma cholesterol which suggests that any effect on a heart disease is going to be relatively small,” Musgrave says.

It’s the same in the case of effect to the thyroid, he says.

“Standard exposure may not do very much at all,” Musgrave says. He calls attention to a Swedish study which found weak or no links between thyroid issues and PFAS.

The correlation with breast cancer may be a similar story, according to a 2014 study.

“There's a lot of speculation, but there's also a lot of evidence that if there is an effect, it's going to be very small,” Musgrave says. In 2017, he penned an article about how PFAS exposure is likely not nearly as dangerous as asbestos, for example.

“The point is about exposure. And for the vast majority of people PFAS exposure is falling. Given that we’ve only really seen health effects with the highest levels exposures or even indications that they might be health effects at the highest level exposures, people shouldn't panic.”

Where are people at risk from PFAS?

“Some communities have tens to hundreds to a thousand times higher levels of contamination, Reade says.

She explains that a lot of NRDC’s work, the organization she works for, concentrates on getting these communities access to clean water, and bio-monitoring their exposure to PFAS chemicals.

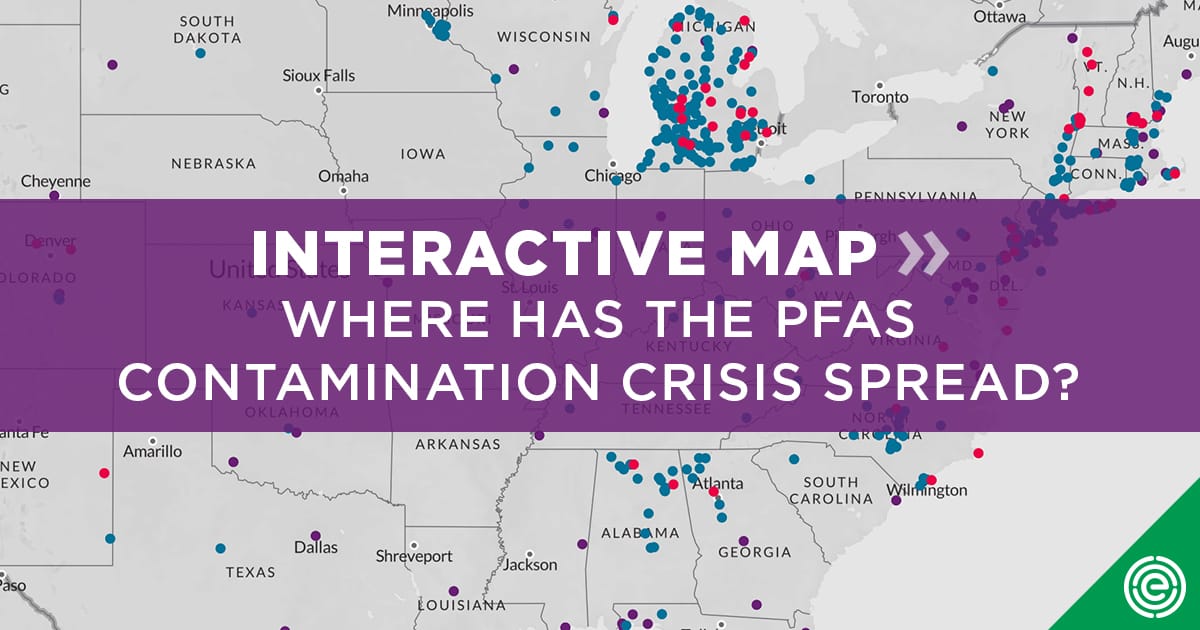

Here is a map of some of the areas in the US that are affected by PFAS contamination:

But overall, "the levels are low, generally far lower than the levels of concern that we tried with established through both animal experiments that human epidemiology,” Musgrave says.

“For the vast majority of people, the health risk from PFAS is negligible," he says. But "for people who have been exposed through industrial exposures or through being firefighters there's a possibility that there might be health risks," he notes.

PFAS and you:

A first step to finding out about PFAS levels in your immediate environment is to look at what you are drinking every day, Schraider says.

“We do recommend that people find out if there has been testing of their drinking water and what those results are,” Schraider says.

For people who have a public water supply, they can contact their supplier, or look up the annual water quality report, also known as a consumer confidence report, she says.

There are also secondary water-treatment systems that filter out PFAS from drinking water, and those can be installed in communities, she says.

“Major manufacturers are moving away from using PFAS because of concerns about public health,” Reade says.

In the last couple of months, The Home Depot and Lowe's have both committed to phasing out selling carpets and rugs treated with PFAS, she notes.

"Most chemicals can be put onto the market without really anything known about them."

But because PFAS are so ubiquitous across so many different products, it will be hard to eliminate them entirely.

Concerned consumers can always contact their favorite brands and ask if they're using PFAS, Reade says.

“Convey to them that that's not something that you want in your products because you don't want that added exposure and risk,” she says. “It's not worth it to you.”

To truly rid ourselves of these potentially toxic chemicals, Reade suggests a two-steps process:

- Stop adding to the problem.

“We're still using PFAS very heavily and in a lot of different areas of commerce and industry. And there are many types of uses that are not necessary. They're not essential for the health and safety of our society and we should stop using those immediately and move away to safer alternatives as quickly as possible.”

- Stop using PFAS all in one go.

One PFAS at a time is just too inefficient to make any meaningful difference, Reade says. “It will take just much, much too long of time and too many resources to do it that way. And during that time, there'll be people that are exposed to these chemicals and suffering.”

Ultimately, the researchers agree that there needs to be more education around PFAS and more research into what — if anything — they do to our health.

Reade says that people often think that if something is used widely, then it must be well-researched, but that is often not the case.

"Most chemicals can be put onto the market without really anything known about them in terms of what they can do to our environment and to our health, Reade says, “And so it's up to scientists to play catch up.”