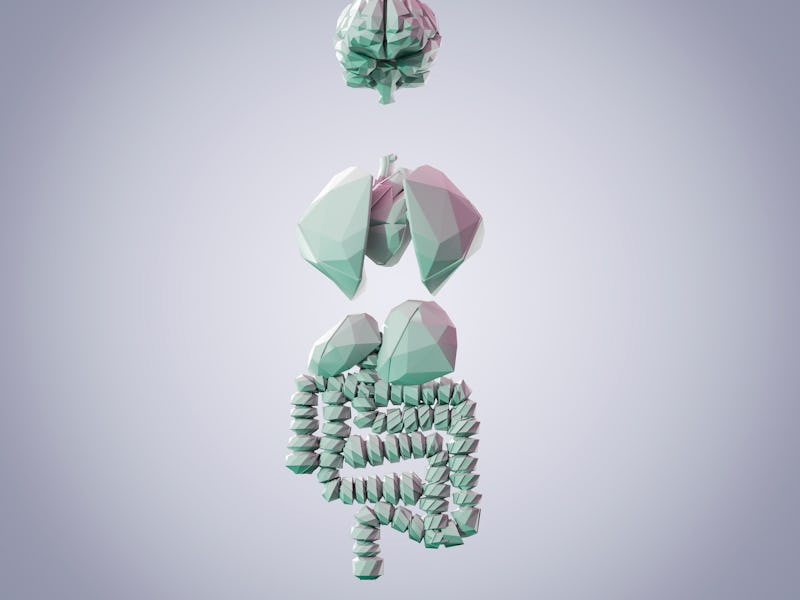

Why the gut may be humans’ “first brain”

This is not science fiction.

Whether it’s diving off a pier into the salty waves below or stepping up to the podium to address a room full of people, you likely know what “butterflies in your stomach” feel like when they start fluttering away inside. In truth, of course, you are not full of literal butterflies — it’s just your brain talking. But this brain isn’t the one in your head: This brain is the one that runs all the way through your body from your mouth to your butt.

Humans have two brains (stay with us): Sometimes nicknamed the “mini-brain,” your gut has its own nervous system made up of more than 100 million neurons working autonomously from the brain in your head to regulate the digestive system.

INVERSE is counting down the ten most-surprising discoveries about your wondrous gut in 2021. This is #2. Read the original story here.

But like the brain in your skull, the enteric system isn’t a one-trick pony: It regulates the immune system, blood flow, and secretes hormones. It’s also in constant communication with the central nervous system, helping to regulate your emotions and mood. But for all we’ve learned about the enteric nervous system, a dozen more questions remain unanswered.

One question stems from the classic “chicken or the egg” problem.

Which came first: The cerebral brain or the gut brain?

That the enteric nervous system evolved to function independently from the brain causes some researchers to argue that the so-called mini-brain came first — Nick Spencer, a professor at Flinders University in Australia, is one of them.

What’s new — Earlier this year, Spencer and his colleagues published a study in support of the “first brain” theory. They showed how gut neurons evolved independently to communicate and control gut muscle movement — a key piece of evidence for that the gut’s nervous system may be our “first brain.”

In the study, Spencer and his colleagues find that neurons from the enteric nervous system send and receive messages to coordinate gut muscle movement. The firing of messages is synchronized to other neurons. Doing so is necessary to move items down for digestion, absorb nutrients from food, and expel waste products.

Here’s the background — Support for the ‘first brain’ theory ironically comes from animals without brains.

Freshwater creatures belonging to the genus Hydra have roamed the Earth for over 600 million years and yet, their tube-shaped bodies function without a brain.

How did Hydra survive for so long? According to Spencer, the hydra evolved a nervous system similar to today’s “gut brain.”

Hydra may be key to understanding how our own enteric nervous system evolved.

“Despite the lack of a formal brain, as we know it, their intrinsic nervous system allows them to swim and feed and ingest food,” he says.

The enteric nervous system plays multiple roles but its main one involves moving food and other items in and out of the gut. The neurons cause muscles in the GI tract to contract and relax, allowing for digestion to take place.

Why it matters — The study adds to the mountain of evidence for the gut’s starring role in your metabolism, brain function, and longevity. One recent study has even found that a diet feeding healthy gut bacteria could reduce multiple sclerosis symptoms.

And for better or for worse, increasing evidence has demonstrated the gut’s influence on your personality — it all depends on the diversity of your microbiome.

But like any other organ in the body, the enteric nervous system isn’t perfect. Studies like Spencer’s can help shift the needle on developing treatments that take this overlooked nervous system into account.

This article was originally published on