Murder, torture, espionage, deceit — being a yakuza is not for the faint of heart.

Honoring a vow to your oath brother might lose you an eye, but leaving a life of crime behind could land your nine favorite orphans (and a gorgeous Shibu Inu) in the line of fire. Sega’s Yakuza series is rooted in the criminal underworld, and its heroes radiate an overbearing macho presence that could make a ferocious tiger cower in fear — maybe even two.

But Yakuza is anything but typical, always at odds with what it was ten minutes prior. The series routinely oscillates between the grave and the absurd — the somber mood of a mysterious murder can be interrupted by the intrusion of a diaper-wearing cult. But one thing that remains consistent is the series’ staunch resistance to the toxic masculinity we see in so many other games. Throughout the series, protagonists like Kazuma Kiryu, Goro Majima, and Ichiban Kasuga consistently unsettle and subvert our expectations of what a man should be — with unforgettable results.

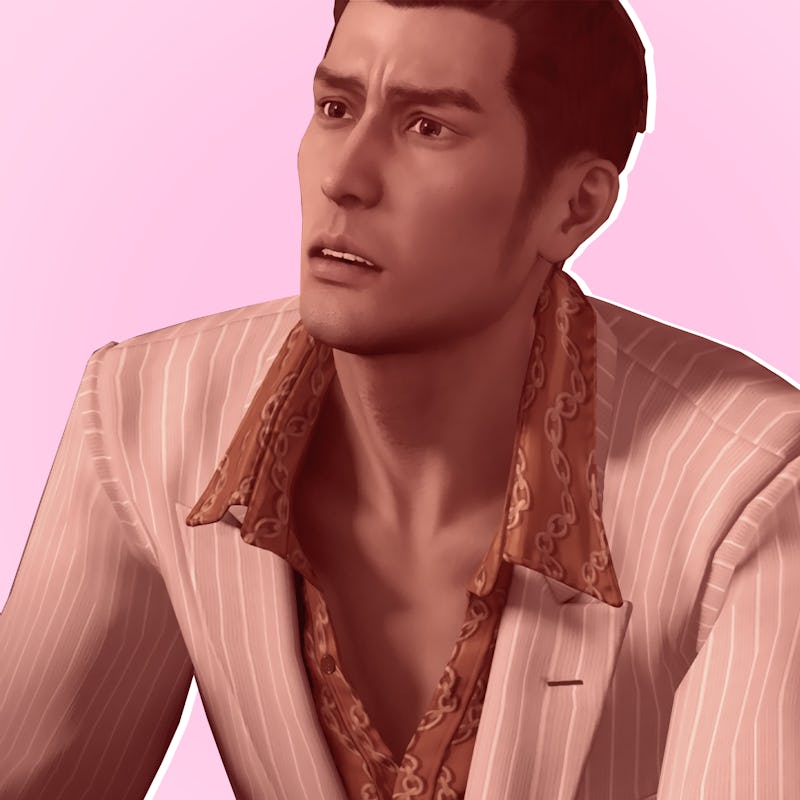

Kiryu

Never one to turn down a stranger in need, Kiryu models for a photo shoot.

Kazuma Kiryu, the protagonist of the series until 2020’s Like A Dragon, is the pinnacle of modern masculinity. He’s six feet tall, wears an expression that could knock a rhino unconscious, and tends to resolve arguments with his fists. To his Yakuza associates, he is the feared and revered Dragon of Dojima, the legendary Fourth Chairman of the Tojo Clan. But by the end of 2009’s Yakuza 3, he becomes a father figure to nine orphaned kids.

No matter where you jump into this sprawling series, you’ll soon realize that Kiryu is nothing like other action game protagonists. But Yakuza 0, the acclaimed prequel released in 2015 in Japan and 2017 internationally, is arguably the best place to start. Early on, 20-year-old Kiryu requests to join the Yakuza along with his adoptive brother, Nishiki. His guardian Kazama responds with a beating and a blunt refusal. In response, Kiryu breaks down, in a scene that sets the entire series in motion.

Why can’t we, Kazama-san? It’s our lives. Our future. We can decide. I owe you everything, but this isn’t about that. And don’t play the saint — you’re Yakuza yourself! Considering that… you have no right to tell us we can’t be Yakuza. You’ve got no right! We’ve looked up to you for all this time. Your car. Your confidence. The way everybody bows to you. We idolized you. I want that life, too. Is that so wrong!? Is that too much? Do orphans not get to dream!?

Kiryu reveres the conventionally masculine aspects of Kazama’s character: his car, his confidence, and the respect he commands. Yet in the moment, he is overcome by emotions and has seemingly lost the faculty of reason. Ironically, it’s this intensity of feeling that convinces Kazama of his strength. Kiryu’s ability to be true to himself is what will ultimately allow him to become the kind of man Kazama himself would respect.

But that vulnerability and willingness to feel emotion are an integral part of Kiryu’s character, both before and after the prequel. When Yakuza 0 came out, some longtime fans of the series were already well-acquainted with the powerful man Kiryu eventually becomes — but many others were meeting him for the first time. To these people, the legendary Kazuma Kiryu was just another grunt, someone who almost wasn’t even allowed to join the Yakuza in the first place. Both perspectives are crucial to understanding Kiryu as a whole.

Do orphans not get to dream!?

Kiryu’s tenderness in Yakuza 0 allows the major emotional beats of Yakuza Kiwami — a remake of the original game from 2005 that stars a 37-year-old Kiryu — to hit even harder. Yakuza Kiwami sees Kiryu protect an orphaned girl named Haruka, and the care he shows for her is a direct reflection of the love Kazama showed him. His mentor’s demise calls back to that fateful night where Kiryu cried out to him in the rain about orphans deserving the right to dream.

“It’s okay, pops,” Kiryu says, cradling Kazama as he draws his final breath. “To me… you were my true father!” Once again, our hero is left crying in the night.

Throughout the series, Kiryu bawls, howls, and weeps — all the while utterly unconcerned with how that might appear to those around him. To many of his fellow Yakuza, this is (wrongly) perceived as a sign of weakness. Nishiki is a perfect counterpoint — the good-natured young man who had been Kiryu’s adoptive brother in Yakuza 0 changes dramatically by Yakuza Kiwami. He becomes cold and clinical, subbing out his flashy suit and bob cut for a white two-piece and slicked-back hair — and speaks to women with sneering condescension.

Good advice.

That last detail is a crucial one. Throughout the series, men like Kiryu, who treat women with respect and kindness, are those most worthy of sympathy and admiration. (Fun fact: when Kiryu shows up as a boss in Like A Dragon, he will never attack the women in your party.)

This attitude has long been a foundational element of the series’ portrayal of masculinity. In a 2020 interview with Red Bull France, series creator Toshihiro Nagoshi said Kiryu would never appear in a fighting game like Smash Bros. or Tekken because, “fighting games usually have female characters, and personally, I don't really want to see Kiryu hit women.”

Kiryu’s treatment of women is surprisingly bashful and nuanced, and his struggles to be suave around the ladies are played to comedic effect throughout the series. While he spends most of his time in the red light district, he is polar opposite to his yakuza brethren who regularly berate or harass cabaret hostesses and waitresses. He treats everyone he meets with respect. In Yakuza 5, Kiryu seems to have had girlfriend for several months, but it’s clearly implied the two have never slept together, despite her wishes.

On one hand, it’s endearing to see a guy who looks like a Men’s Health cover model forgetting how words work every 30 seconds. But this quirk also underscores a rather profound personal sacrifice — being yakuza obliges him to protect civilians, particularly women and children. And for Kiryu, that means never getting too close.

Majima

Goro Majima in his “24 Hour Cinderella” karaoke outfit from Yakuza 0.

This idea is developed further via Goro Majima, the “One-Eyed Demon” and “Mad Dog of Shimano.” He’s Kiryu’s best frenemy throughout the series, and the co-protagonist of Yakuza 0. Majima is missing an eye, dons a snakeskin blazer, and often licks the pointy part of his tantō — everything about the way he presents himself is done with the intent of being intimidating. And for most of the series, that’s what he is.

As is the case with Kiryu, Yakuza 0 shows us a softer, scrappier Majima than other games in the series. Before he became captain of the Shimano family, Majima was the manager of the Cabaret Grand, a premier hostess club in Osaka’s vice district of Sotenbori. While young Majima is more confident and brash than Kiryu, he is similarly uninterested in the women around him — as a yakuza, he’s obliged to keep his distance.

But Majima has one exception to this rule: Makoto Makimura.

Like Kiryu is willing to leave the yakuza life behind to run Morning Glory Orphanage, Majima offers to quit the family for Makoto. After being ordered to murder her, he falls in love with her, putting her life before his own on several occasions.

“Personally, I don't really want to see Kiryu hit women.”

The most critical moment of their relationship comes a whopping 18 years later. In Yakuza Kiwami 2, Majima stops by the Osaka clinic where Makoto used to work, and finds she’s still there. (She doesn’t recognize him, because she was blind for most of their adventures in Yakuza 0.) He suffers through a massage treatment as she talks through her concerns about leaving Japan with her husband.

Later, Majima sends Makoto a replacement strap for her watch, a treasured keepsake from her brother that figures prominently in the final moments of Yakuza 0. The gift gives her closure and affirms her decision to leave the country. Meanwhile, Majima is left to wonder — and mourn — what might have been.

Ichiban

Ichiban’s enthusiasm is contagious throughout Like A Dragon.

Ichiban Kasuga, the protagonist of Yakuza: Like A Dragon, is less of a wandering, solitary warrior and more of a happy knight. He’s more interested in channeling his inner Dragon Quest hero than his inner Dragon of Dojima. Nevertheless, he’s cut from the same cloth as the conflicted and complicated protagonists of Yakuza 0.

Ichi is Kiryu’s ideals incarnate, the physical manifestation of joy, kindness, and unrelenting selflessness. Even Ichi’s suit is a direct inversion of Kiryu’s — he wears a maroon two-piece with a grey dress shirt, as opposed to a maroon shirt and gray suit. They are two sides of the same coin, united by the drive to affect good through empathy and kindness. What’s more, Ichi might be the only person in the world who cares about other people’s opinions even less than Kiryu does.

This is best exemplified in a scene towards the end of Like A Dragon, where Ichi convinces the man he considers a brother, Masato Arakawa, to turn himself into the police instead of taking his own life.

“That’s not it at all! You know why Arakawa-san, Sawashiro, and I never gave up on you?! I’ll tell you. There’s no logic to it. It was because deep in our hearts, we felt a connection to you! It’s not some kinda clear-cut, love-it-or-hate-it kind of emotion! You say no one appreciated you?! Bullshit! No one could stand to let you go! We never once abandoned you.”

Though victory is in his grasp, Ichi isn’t interested in one-upping Masato. Despite having all of the power in this situation, he weeps and even begs. The only thing he wants is for his brother to feel loved.

Ichiban and Masato in a heated exchange from late in Yakuza: Like a Dragon.

Throughout this series, what it means to be a yakuza is all but impossible to separate from what it means to be a man. And that, ultimately, is what unifies all three of the series’ most memorable protagonists: brotherhood. Only the very best of friends or most formidable rivals — in this series, they’re sometimes the same person — are worthy of being called “brother.”

Yakuza resists toxic tropes in a way that makes it easy to appreciate a healthier kind of masculinity in real life. When Kiryu cries uncontrollably, Majima gets a lump in his throat, and Ichi weeps, you realize even the hardest people have soft interiors. These characters are never afraid of expressing their feelings, or treating vulnerable people with kindness. That — more than six-packs and sawed-off shotguns — is true strength.