Cold War-era spies are being recruited to help climate scientists

The United States was very motivated to "study" this hard-to-access region back in the '70s...

The Himalayas are known as Earth’s “third pole” for their massive glaciers. The water they store is an important source of drinking water for billions of people in South Asia. But as the climate warms, those glaciers are melting — with potentially dire consequences for the humans that depend on them. Thing is, the area is hard to get to, and thus, hard to study, so it was difficult to say how much they’ve changed over time.

But thanks to Cold War-era satellites, scientists can now see the dramatic loss of ice in these glaciers across the last 40 years. The findings were published in July 2019 in the journal Science Advances.

The data paint a dark picture for the iconic mountain region. But how the researchers got the original data in the first place is a scientific victory that demonstrates how “eyes in the sky” launched during a weird period of American history can be recruited to further today’s global science efforts.

This is #20 on Inverse’s 20 most incredible stories about our planet in 2019.

Cold War comes full circle

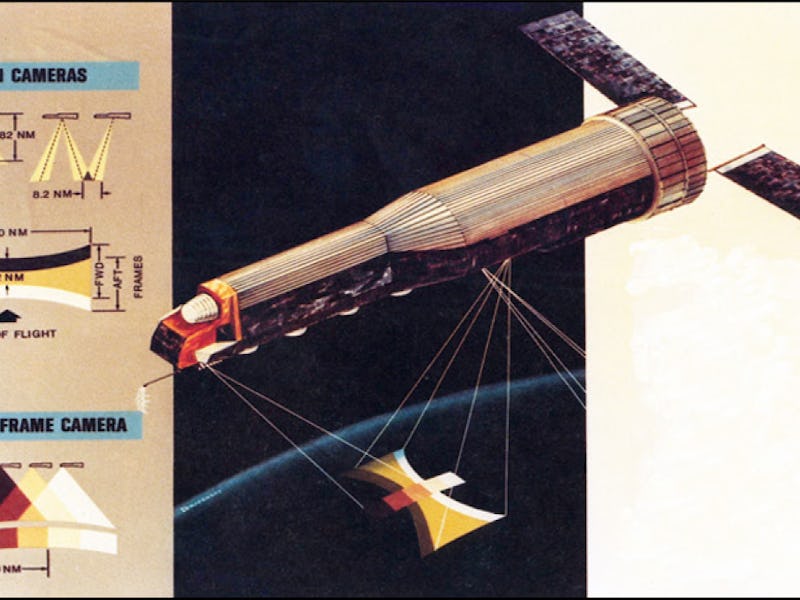

In the 1970s, the United States launched the Hexagon KH-9 surveillance satellites. These spies in the skies were designed to collect crucial intelligence on Soviet activities as they surveyed over 877 million square miles of the Earth’s surface.

Between 1973 and 1986, the satellites captured film images that were collected and analyzed by the US National Reconnaissance Office.

Comparing those early images against modern satellite photos reveals that the Himalayan glaciers have so far lost twice as much ice in the 21st century as they did in the 20th.

The Hexagon KH-9 satellite system.

Researchers estimate that, beginning in 1975, glaciers lost an average of 10 inches of ice per year. After 2000, that rate accelerated rapidly, to 20 inches of ice loss annually across the 650 glaciers in the region. At lower elevations, the rate is way higher — around 16 feet per year.

For the glaciers to decline that quickly, researchers say that regional temperature would have to have increased by 0.4 - 1.4 degrees Celsius after 2000.

Local meteorological measurements confirm their hypothesis: Air temperatures in high mountain Asia were an average of about 1 degrees C warmer between 2000 and 2016 compared to the 1970s.

“Reduced meltwater contributions to rivers, which will change the timing and magnitude of water supply in heavily populated downstream regions in the coming decades,” said researcher Josh Maurer at the time.

These US spy satellites succeeded in their mission. They’ve tracked the enemy’s activities and provided valuable intel that could likely save millions of lives. But what we didn’t expect was that the 40 years later, the enemy would be ourselves.

As 2019 draws to a close, Inverse is revisiting the year’s 20 most incredible stories about our planet. Some are gross, some are fascinating, and others truly are incredible. This has been #20. Read the original article here.