Drug Researchers Find Brain Effects of MDMA Have Been Misread All Along

Studies don't actually represent typical MDMA users.

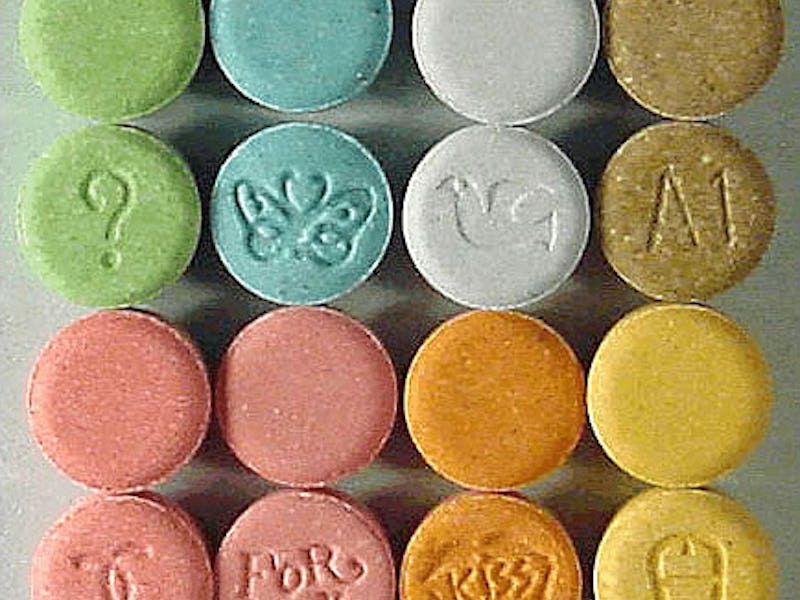

Anyone who took DARE in elementary school probably heard about how taking too much MDMA (aka ecstasy) will put holes in your brain. And in this, the year of our lord 2018, we all know that’s bullshit. But that begs the question: How harmful can MDMA actually be for your brain?

In recent years, scientists have renewed efforts to study the benefits of MDMA for treating post-traumatic stress disorder, as well as the possible risks associated with taking too much recreationally. Researchers have focused most closely on the way MDMA depletes the neurotransmitter serotonin in people’s brains, finding that heavy, frequent use can have long-term consequences on brain chemistry and physiology that are slow to heal. In opposition to that growing body of research, though, a new paper suggests that some of the harmful effects of MDMA may have actually been overstated.

The paper, published May 7 in the Journal of Psychopharmacology, shows evidence that harmful long-term effects of MDMA are probably caused by very high doses that most people don’t actually take. To conduct the study, researchers compared two resources: ecstasy use reported by participants in 10 different serotonin imaging studies and the data from the Global Drug Survey, which the study’s authors call “the world’s largest survey of recreational drug use.” Based on the numbers gleaned from the Global Drug Survey, the paper’s authors determined that the harm identified by the imaging studies is based on a sample of the population that doesn’t represent the ways in which people actually use MDMA.

Surprisingly, many ecstasy users don't realize that Molly, MDMA, and ecstasy are all the same thing.

When the study’s authors, led by Balázs Szigeti, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Edinburgh, dug into the available data on ecstasy use, they found that the numbers simply don’t add up. In the Global Drug Survey, which includes recreational ecstasy use data from 11,168 people, ecstasy users reported they took a usual amount of 1.5 pills per session about 0.67 times per month, which means they took an average of 12.2 pills per year — a number the researchers call Dose Intensity. But when they looked at the usage rates for people in the neuroimaging studies, they found these individuals reported an average of 2.7 pills per session, taken about 2.6 times per month, for a grand total of 87.3 pills per year.

This means that the people whose serotonin levels and function were being measured in the lab were actually taking much, much more MDMA than the typical user.

“Both the average Usual Amount and Use Frequency of neuroimaging study participants correspond to the top 5–10% of all ecstasy users, and their estimated Dose Intensity is 720% higher than the recreational users’,” write the study’s authors.

Therefore, it’s likely that much of the available data on the possible long-term effects of MDMA use will only actually apply the top five to 10 percent of ecstasy users. The study’s authors point out a potential explanation for this over-representation of heavy users: Researchers are more likely to recruit heavy users so they can actually show an effect. “Nonetheless, the unusually heavy user samples should be taken into consideration when interpreting these publications,” write the study’s authors.

Further research will be necessary to determine how long-term use of more typical levels of MDMA affect people’s brains. But for now, it’s safe to say, don’t roll all the time.

Abstract:

Background: Neuroimaging studies imply that the regular use of ±3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), the major constituent of ecstasy pills, alters the brain’s serotonergic system in a dose-dependent manner. However, the relevance of these findings remains unclear due to limited knowledge about the ecstasy/MDMA use pattern of real-life users.

Aims: We examined the representativeness of ecstasy users enrolled in neuroimaging studies by comparing their ecstasy use habits with the use patterns of a large, international sample.

Methods: A systematic literature search revealed 10 imaging studies that compare serotonin transporter levels in recreational ecstasy users to matched controls. To characterize the ecstasy use patterns we relied on the Global Drug Survey, the world’s largest self-report database on drug use. The basis of the dose comparison were the Usual Amount (pills/session), Use Frequency (sessions/month) and Dose Intensity (pills/year) variables.

Results: Both the average Usual Amount (pills/session) and Use Frequency (sessions/month) of neuroimaging study participants corresponded to the top 5–10% of the Global Drug Survey sample and imaging participants, on average, consumed 720% more pills over a year than the Global Drug Survey participants.

Conclusions: Our findings suggest that the serotonin brain imaging literature has focused on unusually heavy ecstasy use and therefore the conclusions from these studies are likely to overestimate the extent of serotonergic alterations experienced by the majority of people who use ecstasy.