Star Trek Doesn't Need to Squash Beef with God

Gene Roddenberry was no saint, but he wasn't a "new atheist" either.

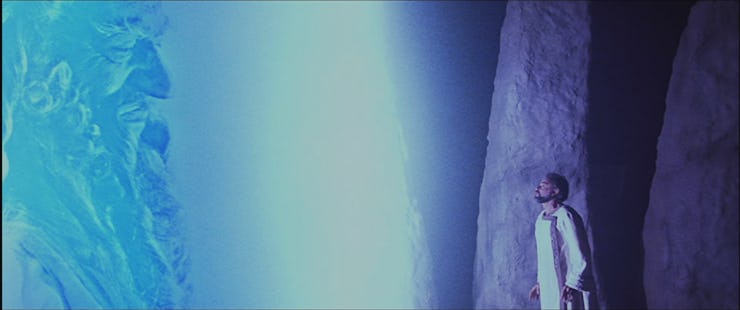

Standing in the radiant blue light of God’s disembodied head, Captain Kirk holds up one finger. “Excuse me,” he says, “what does God need with a starship?”

It’s a fair question, albeit not the sort of query deities commonly receive in pop culture. This scene from Star Trek V: The Final Frontier blurs the line between the inhuman and the divine in a less than subtle way, but the clunkiness doesn’t undermine its significance within the Star Trek canon. It represent the clearest example of the venerable sci-fi franchise tackling the big question of religion. “What does God need with a starship?” is a neat rephrasing of the real question: If mankind can innovate its way to godlike powers and peace, does the all-powerful become redundant?

The answer to that question and the question of whether or not Star Trek is inherently anti-religious has become more complicated for one clear reason: The shows ideology doesn’t conform to modern assumptions about religion and politics — or politics at all for that matter.

At the end of the Jesus-heavy, original series episode “Bread and Circuses,” Dr. McCoy says “We represent many beliefs.” The Vulcan philosophy of IDIC (“infinite diversity in infinite combinations”) also asserts a pluralistic view of various faiths. And yet, Trek’s creator – the late Gene Roddenberry – seemed to have harbored an overwhelmingly antipathy for organized religion, one he weaponized in his writing for the original Star Trek series, the animated series, and early movies that were never actually made.

An unproduced 1970s Roddenberry script entitled “The God Thing” featured Captain Kirk punching a faux-Jesus out on the bridge of the Enterprise. While similar false-god unmaskings occur in The Final Frontier, Trek never went as far as to actually rough up relatable prophet. Still, there does seem be a knee-jerk anti-religion tendency in Treks DNA. “When in doubt,” Star Trek writer and author David Gerrold said, “Gene always had Kirk get into a fight with God.”

Part of the apparent anti-religion of the franchise may have to do with assumptions about politically positioning. The shows and movies scan as, if not overtly politically leftist, politically progressive. “Star Trek has enormous snob appeal,” according to long-time Trek producer Harve Bennett, “It purports to be a program for the bright.” Progressive and a bit pompous? Sounds like the sort of political leaders who have historically gone after religious leaders. Of course neither intelligence nor inclusiveness preclude faith, but it’s hard to shake a first impression. One generally needs outside help to do that.

23rd century "liberals" and "conservatives" clash in 'Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country'

In 1975, Jacqueline Lichtenberg, Sondra Marshak, and Joan Winston co-authored a nonfiction book called Star Trek Lives!, which strongly pushed an argument that Ayn Rand’s objectivist theories about art are intrinsically part of Star Trek’s messsage. This book included unprecedented contributions from Roddenberry and the original Star Trek cast. Obviously, Rand’s theories about “reality” are largely rejected by leftist thinkers, meaning that a contemporary “liberal” Star Trek fan might find it more than a little troubling that one of the first serious works of nonfiction about Trek contained many philosophies that might seem incompatible with their own political or ideological beliefs. If Star Trek stories are what contemporary writers refer to as “message fiction,” how come they attract people with opposing viewpoints? One answer to this question may relate to the franchise’s godlessness. Ayn Rand was an atheist. One could argue that the venn diagram between the far left and the libertarian right is a general indifference to faith.

At the start of the Trek series Deep Space Nine the deities worshiped by the Bajorians – the prophets – are revealed to be extraterrestrials, or as the human Star Fleet people call them “wormhole aliens.” And yet, the faith of various Bajorian characters (notably Kira) isnt shaken by this revelation. She seems comfortable with the idea that her gods’ holiness is a reflection of faith, not a reason for it.

'Deep Space Nine's' Captain Sisko just before his martyrdom

“God is already ‘alien,’ in Christian theology,” Michael Poteet explains. “Completely other, radically different, outside space and time.”

Poteet is an ordained minister in the Presbyterian Church, a longtime Star Trek fan, and a writer. Not only was one of his original Star Trek short stories published in the officially-licensed Star Trek anthology Strange New Worlds in 1999, he contemporarily writes for The Sci-Fi Christian. It seems for Poteet, that Captain Kirk’s unmasking of false Gods isn’t anti-religious at all. Instead Poteet views Kirk as a “reformer” who actually objects to problematic religions. “I’d argue the gods Kirk brings down—Landru, Apollo, Vaal—are problematic not because they’re objects of worship and service or want to be per se, but because the worship and service they receive or demand are dehumanizing,” Poteet tells Inverse. “They’re degrading. They don’t ennoble the worshipers and servers.”

Still, how do theological thinkers like Poteet untangle their love of Star Trek from Roddenberry’s seemingly aesthetic stance? Kevin C. Neece, author of the forthcoming book The Gospel According to Star Trek, and creator of The Undiscovered Country Project: Christian Perspectives on Star Trek admits freely that “Roddenberry rejected his Christian background,” but maintains that “[Star Trek’s] humanism is deeply spiritual and can help us recover the beauty of the image of God in our humanity.”

In the series finale of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine – “What You Leave Behind” – Benjamin Sisko literally becomes a martyr and joins the “prophets” in the celestial temple. According to showrunner Ira Steven Behr, “The fans consider Star Trek captains to be gods to begin with, so we might as well make one an actual god.” Here the line between the intention of the Star Trek writers and the result seems to get blurry. Sisko (like Spock before him) becomes something of a Christ-figure by the end of his Star Trek story.

“When I draw Christian parables from Star Trek, I acknowledge I’m seeing things the authors and actors probably didn’t intend,” Michael Poteet told Inverse. “But authorial intention only goes so far once a work of art is unleashed upon the world, and I believe God is free to speak using whatever media God chooses, even a secular science fiction show.”

So, it’s not as though Behr, or the writers on Deep Space Nine, or any other Star Trek for that matter, was creating overtly Christian messages. But, when we realize the various writers of Star Trek are also not necessarily creating anti-religious or atheistic messages either, the interpretation of this vast fictional universe suddenly becomes a whole lot bigger. In a truly inclusive universe, gods have the some of the same needs as their followers. And sometimes they need a ship.