Lonely people's brains are different in 3 major ways

There’s a rich inner world inside every lonely mind.

When the health insurance giant Cigna surveyed 10,000 adults in 2019, they found a surprisingly forlorn world: 61 percent of people surveyed said they felt lonely.

However, loneliness is more than a feeling. Scientists suggest loneliness lights up the brain the same way basic human needs, like hunger, do. Newer research is showing it's also related to changes in the brain — proof there's a rich inner world inside every lonely mind.

The default mode network is a large scale network in the brain that connects several far-flung brain regions. It’s the system that’s activated when we daydream, dwell on the past, or plan for the future. It’s also a network that seems to be strengthened in lonely people, according to the results of a study published Tuesday in Nature Communications.

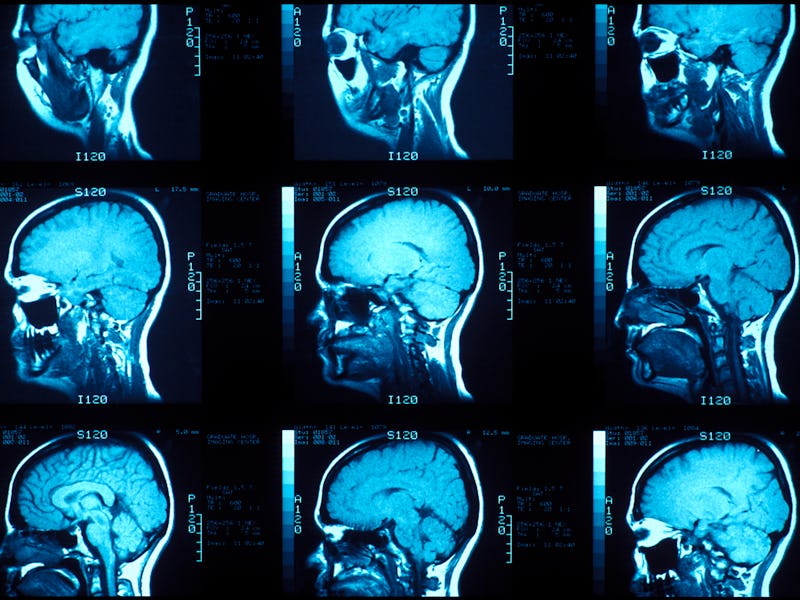

Using a sample of brain scans from the UK Biobank, a large-scale biomedical database, scientists at McGill University found loneliness was linked to three changes in the brain:

- Higher grey volume in areas of the brain involved in that network.

- Greater connectivity in the default mode network

- Heartier structure in a bundle of nerve fibers called the fornix, which carries signals from the hippocampus to that network

Nathan Spreng, a professor at McGill University and the study’s first author, tells Inverse that these are signs that the brain may adapt to loneliness creating a social world in our heads.

“Lonely people tend to imagine the social world to a greater degree, as well as reminisce about social experiences more," Spreng explains. "We think that in the absence of social stimulation in the world, the brain is compensating by up-regulating these functions of the default network."

Yellow areas of the brain had higher grey matter volume in lonely people, green areas showed lower grey matter volume. But overall, lonely people had more grey matter volume in the areas of the default mode network.

Can loneliness change the brain?

This study examined brain scans taken from 38,701 people in the UK Biobank database. Thirtneen percent of people in the sample analyzed reported they felt lonely, according to surveys given to participants as part of the BioBank project.

When the team looked for patterns in their brain structure and activity, they found that the brain contained those three signs of change.

This study can’t tell us that loneliness causes these changes in the brain. For now, Spreng hypothesizes that loneliness may be a driver of these physical changes. This is because brain is known to be capable of adapting itself.

The neuroscience of loneliness — Leaning a new skill, like a musical instrument, can strengthen existing connections in the brain. There’s some evidence that emotions can also impact brain structure. A study on 50 women found that those who regularly suppressed their emotions had higher volumes in certain areas of the brain.

Loneliness may be a physical situation and an emotional experience. Studies on loneliness suggest this isn’t just a consequence of not having people around, it’s a perception that there’s a gulf between ourselves and other people.

The brains of lonely people tend to show different patterns of activation when they think about themselves and others (even people close to them), and lower levels of activity in the medial prefrontal cortex compared to non-lonely people, a 2019 study found. Those study authors suggested that loneliness may arise from a perceived “gap” between yourself and those around you — even if you’re surrounded by close friends and family.

Our brain’s temporary answer, this study suggests, is to compensate by enhancing the network in our brain that can replay and relive the interactions we’ve had before.

“We think this has something to do with how social humans are, and the importance of being immersed in a connected social environment,” says Spreng. “In the absence of this experience of social connection, the brain appears to compensate.”

Do the changes last? — If loneliness really is driving these changes — and, for now, Spreng thinks that’s the case — then it’s fair to wonder if they’ll last forever. At this point, Spreng doesn’t think that they will.

“The brain is dynamic in addressing challenges we face, so we suspect that a rich, social immersion would offset the differences we find,” he says.

During a pandemic, those rich social environments may feel hard to come by, but there is some positive news: While loneliness seemed to be on the rise pre-pandemic, the current catastrophe may also coincide with a shift.

One survey published in American Psychologist found that loneliness may have actually leveled off during the pandemic. In a sample of 1,500 people surveyed before the pandemic, again in late March, and later in April (while many states imposed stay-at-home orders), the team found loneliness stayed relatively stagnant. Instead, the team found that people believed that they were receiving increased support from others.

The team found the results “a sign of remarkable resilience in response to Covid-19.”

Given the fact that our brains may adapt and react to social interaction, Spreng says now is the time to lean into those relationships (especially when we have the end of the pandemic in sight).

“Reducing loneliness can also mean leaning in closer to our friends and family," he says. "Now more than ever."

Abstract: Humans survive and thrive through social exchange. Yet, social dependency also comes at a cost. Perceived social isolation, or loneliness, affects physical and mental health, cognitive performance, overall life expectancy, and increases vulnerability to Alzheimer’s disease-related dementias. Despite severe consequences on behavior and health, the neural basis of loneliness remains elusive. Using the UK Biobank population imaging-genetics cohort (n = ~40,000, aged 40–69 years when recruited, mean age = 54.9), we test for signatures of loneliness in grey matter morphology, intrinsic functional coupling, and fiber tract microstructure. The loneliness-linked neurobiological profiles converge on a collection of brain regions known as the ‘default network’. This higher associative network shows more consistent loneliness associations in grey matter volume than other cortical brain networks. Lonely individuals display stronger functional communication in the default network, and greater microstructural integrity of its fornix pathway. The findings fit with the possibility that the up-regulation of these neural circuits supports mentalizing, reminiscence and imagination to fill the social void.