Study: Multiple sclerosis patients have a different gut microbiome

The condition has confounded scientists. Do bacteria in the gut hold any answers?

Multiple sclerosis still baffles scientists. Theories exist, but researchers still don’t understand what triggers the immune system to attack healthy nerves.

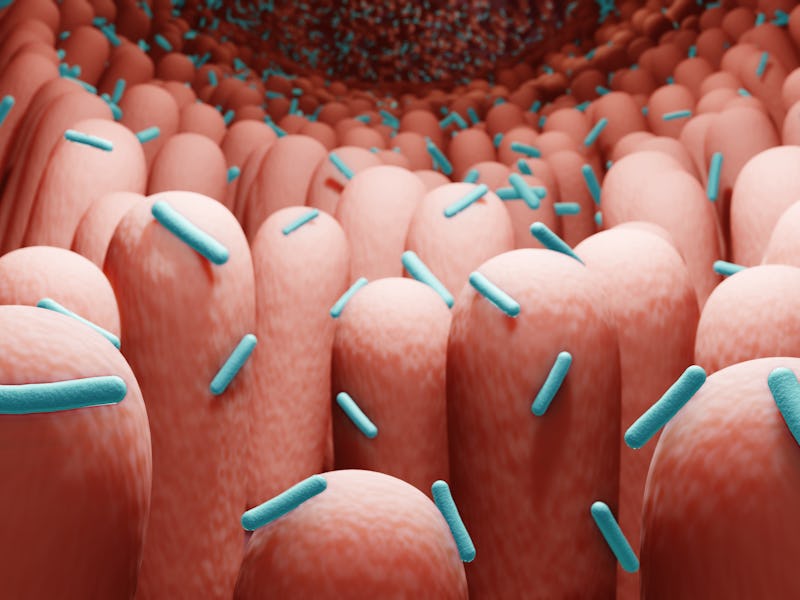

In a new study, researchers found that the microbiomes — the ecosystem of viruses, bacteria, and fungi that reside in our guts — of people with MS are distinct from those without the disease. Understanding why this difference exists could help researchers better understand and treat the condition.

Scientists have been stifled by the enduring mystery of why the immune system mounts this attack on healthy nerves.

What’s new — In a study published last month in the journal EBioMedicine, researchers found that a group of people with MS had markedly different bacterial ecosystems in their guts compared to a similar cohort without MS.

In multiple sclerosis, the immune system attacks the protective sheaths of nerve fibers, disrupting the communication between those nerves and our brains. Researchers do not know why people develop the condition and have been left with a baffling list of risk factors: Caucasians are more likely to develop MS, and women are more likely to develop one type. MS is more prevalent in colder climates, and a history of certain infections might play a role in triggering the condition.

To examine the disease from another angle, a team of researchers, led by Washington University School of Medicine and the University of Connecticut’s clinical health unit, looked at the eating habits and digestive and metabolic characteristics of 24 people newly diagnosed with the condition. MS patients enrolled in the study had markedly different blood metabolites and microbiome contents than people without MS. They also, on average, ate more than twice as much meat.

Further research is needed to determine the significance (if any) of these correlations and how they might contribute to an understanding of MS.

Why it matters — Multiple sclerosis afflicts 2.3 million people globally and can be debilitating, sometimes causing severe handicaps.

Many treatments are available, but there is no cure, and scientists have been stifled by the enduring mystery of why the immune system mounts this attack on healthy nerves. So every new angle could help.

The gut microbiome helps train and develop the immune system. Researchers know that diet plays a crucial role in shaping what species reside in the gut and in what amounts, so perhaps there are insights to be taken from looking at the digestive and metabolic health of people with MS.

Yanjiao Zhou, one of the coauthors, tells Inverse that this small study is a first crack at examining MS from a new perspective — with the technology that allows scientists to sequence gut bacteria from a stool sample and identify the telling aftereffects of metabolism as seen in the bloodstream, plus the knowledge that all these facets are connected.

“This paper is really just to try to leverage all this technology together, and try [to] review the association between all these components,” she says.

Zhou says that some of the bacteria lacking in MS patients have anti-inflammation properties. Inflammation is correlated with a host of chronic conditions, particularly autoimmune ones.

Also, there were differences in the gut microbiomes between those with mild and severe symptoms, which “suggest[s] that specific gut microbes may be associated with the degree of disability in MS patients,” according to the paper.

The most significant dietary difference between the 24 MS patients and 25 healthy people recruited as a control group was meat consumption. The MS patients ate 2.7 servings of meat for every serving eaten by the control group.

Previous research into MS and meat consumption have had inconclusive results. One study showed a higher prevalence of MS among people with high animal fat intake and a lower prevalence in vegetarians. But another study found that people with increased consumption of non-processed red meat had a reduced risk for neurological activity associated with MS. The authors noted that red meat is high in vitamin D and other components that have a neuroprotective effect.

Investigating this further, the researchers behind the new paper used the microbiome data to determine that, in their pool of participants, high meat consumption was correlated with a lack of B. thetaiotaomicron, a gut bacteria that helps the stomach digest carbohydrates.

Interestingly, the presence of that same bacteria “was strongly negatively correlated” with high circulation of an immune system component called T helper 17 cells. Scientists have thought T helper 17 cells play a role in the immune system’s haywire behavior in MS.

But all of that is inconclusive. As for what this means for one of medicine’s most frustrating conditions, only time and further research will tell.

Study participants with MS ate twice as much red meat as those who did not have MS. Research on MS and meat consumption has largely been inconclusive.

How They Did It — The researchers recruited 24 newly diagnosed patients with as-yet untreated MS.

They also recruited 25 healthy people and populated that group to match approximately the age, gender, race, and body mass index of the MS group. They used this control group to tabulate what was standard.

The researchers had both groups complete food diaries and submit blood and stool samples.

What’s Next — Zhou and her collaborates would like to do another study with more people to test the consistency of these findings. They would also like to include people with more severe MS to investigate the finding further that the microbiome deviates even further from the norm depending on the severity of the disease.