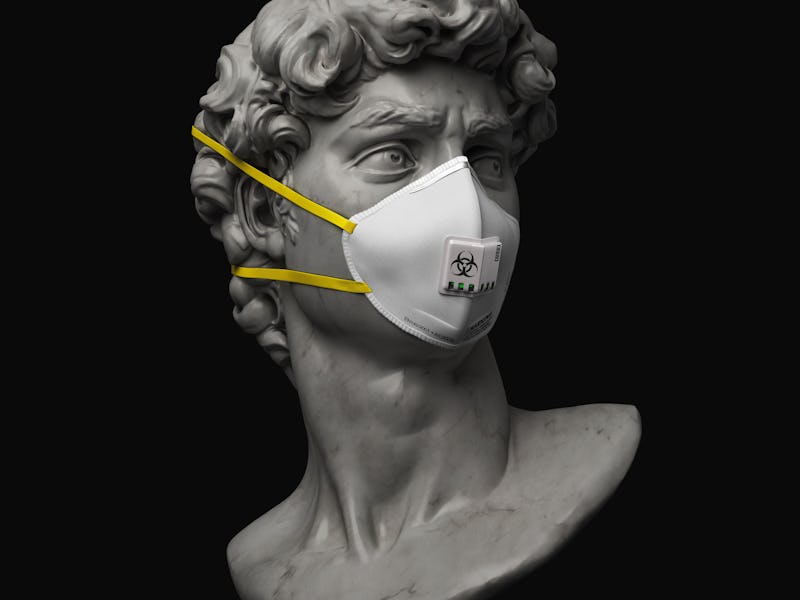

An unexpected trait can help certain people adjust to our 'new normal'

Recent research explores the "psychological immune system."

Since the pandemic began, there’s been a lot of conversation around the “new normal.” The new normal is our life — it’s how we spend the day-to-day now that we live with Covid-19.

Here’s the bizarre part: While we are living with this terrible thing, some days do feel normal. There are moments when I’m cooking dinner with my boyfriend, or I’m playing a board game with my housemates, that I forget we are living in a pandemic. This, of course, is a situation made possible by privilege. Covid-19 is synonymous with catastrophe, and millions have been hit impossibly hard by health and economic battering rams.

Still, still. There is a strangeness in remembering, in feeling normal. It’s something that Eric Anicich, an assistant professor of management at USC’s Marshall School of Business, has felt too. Anicich is the first author of a study forthcoming in the Journal of Applied Psychology on psychological recovery during Covid-19.

“I waver between feeling shocked that we are living through a global pandemic and forgetting that we are living through a global pandemic,” Anicich says. “Part of the reason I temporarily forget that we are living through the pandemic is because I often find myself doing ‘normal’ things. Partly, this is out of necessity. We all have responsibilities that we need to continue to fulfill and challenges that we still need to address individually and collectively.”

The "new normal" — Anicich and his colleagues originally intended to study something else, but when they began to design the study, it became clear they had a unique opportunity to study employees' reactions to the early days of the pandemic. Beginning on March 16, the team spent two weeks surveying 122 people several times a day about how they were experiencing the pandemic.

Ultimately, they found that, while people felt powerless and less authentic to themselves at first, a sense of normalcy had started to return just two weeks later. This suggests people establish a sense of a “new normal” while still feeling stressed and worried. It’s a finding that runs counter to previous research suggesting recovery can only start after stressors cease.

Anicich credits this to something he calls our “psychological immune system,” a term that encompasses a bundle of nonconscious processes that protect us when we experience distress. Ego defense mechanisms figure prominently in the psychological immune system — It could be worse, others are going through something much harder. — and so is the rationalization of circumstances. This allows us to see them in a more favorable light, Anicich says. It’s when we say things like, While I miss being around other people, at least I don’t have to commute.

“I waver between feeling shocked that we are living through a global pandemic and forgetting that we are living through a global pandemic."

One related concept, he explains, is “impact bias,” which refers to when humans overestimate how intensely and for how long they will experience a positive or negative emotional state following a positive or negative outcome.

The majority of past studies on psychological recovery following a complex stressor examine these things over very long periods of time.

“Often, researchers do not even begin collecting data related to the recovery process until months or years after a discrete stressor has abated,” he says. “One of the interesting aspects of our study is that we were able to examine the psychological recovery process in the days immediately after the onset of an ongoing stressor.”

The road to resilience — But whether or not we are becoming resilient is something we can not say for sure just yet, says Dr. Igor Linkov, an adjunct professor at Carnegie Mellon University and team lead at the US Army Corps of Engineers. He is the co-author of the book The Science and Practice of Resilience and was not involved in this study.

Linkov specializes in examining how risk-taking and resilience play out in various situations, ranging from homeland security to epidemic outbreaks. In a 2019 paper titled “Resilience Strategies and Approaches to Contain Systemic Threats,” he and his coauthors astutely note that, through a resilience approach to threats, systems accept transitions to new phases. “New normals are normal,” they write.

This is also helpful when thinking about a person. Linkov tells me that the US National Academy of Sciences frames resilience through the phases: respond/absorb, recover, and adapt.

“I believe that this study has measured absorption capabilities, which are distinct from recovery capabilities,” Linkov comments, referencing Anicich’s work.

“The metrics are novel and useful for understanding absorption. Measurements for recovery, and therefore the full manifestation of resilience, would have to wait until the pandemic has meaningfully abated or passed.”

When it comes to considering who is particularly good at absorption, Anicich’s study offers a hint: neurotic people. He and his team found that while neurotic people were more anxious and nervous at the onset of the study, they also recovered at a faster rate.

“Neuroticism gets a bad rap,” he says. “However, neuroticism confers an evolutionary advantage in that it is associated with greater vigilance in the face of environmental threats.”

It’s a mindset that, he notes, “can be highly functional in the context of a global pandemic.” Meanwhile, a risk that comes with normalizing the pandemic, Anicich explains, is that doing so can cause some people to become complacent. Although it may be true that people can adapt to stressful circumstances quickly, this can’t translate into decreased interest in eradicating the stressor.

This article was originally published on