“We're missing out on many ways that we can make something better.”

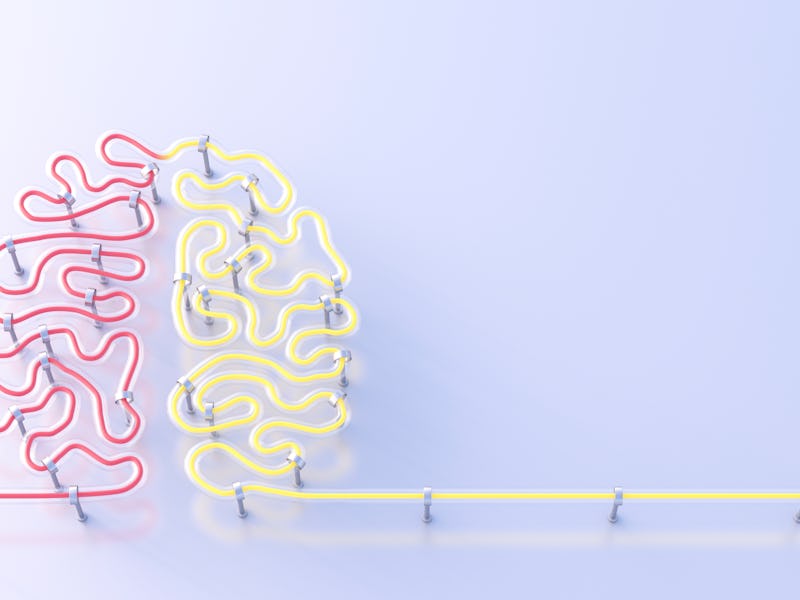

You need to start using this psychology-based productivity hack

A strange part of human psychology holds us back from solving problems, a new study reveals.

by Katie MacBrideWhen we try to solve a problem or improve a design, we typically think something needs to be added to the existing model. It’s much harder for us to think about subtracting something to solve a problem.

This flaw in thinking ultimately makes us worse at fixing an issue, scientists report in a study published Wednesday in Nature.

This human psychology snafu can be found everywhere — extra meetings to figure out why work schedules are too cramped, the red tape of bureaucracy; leaning on technology to solve the climate crisis. But perhaps most elegantly, this problem is apparent in the way we learn to ride a bike.

Background — If you’re like most millennials, you probably started on a bike with training wheels. But that’s not the most effective way to learn how to ride a bike. The biggest obstacle for kids to overcome when learning how to ride a bike is how to balance.

That’s why the Strider was invented — a “balance bike,” with no peddles that allows a child to practice balancing on a bike while keeping their feet safely close to the ground. Its creator, Ryan McFarland, realized less is more and invented a more effective way to learn.

Why did it take decades for someone to come up with this prodigious but simple idea? The new study, led by researchers from the University of Virginia, might have the answer: When wanting to improve something, it’s a human tendency to add rather than subtract.

Social science researchers Gabrielle Adams, Benjamin Converse, and Andrew Hales give engineer Leidy Klotz credit for the study idea. Klotz researches the intersection of design and social behavior. He noticed that people tended to add things to design models and rarely considered removing something from the same models.

“Somebody once asked us ‘why has no psychologist studied this before,’” Converse tells Inverse. “And I think the short answer is it took an engineer to notice the absence of this behavior.”

What they did — The researchers asked 1,153 participants to solve various problems. These included solving a geometrical puzzle, stabilizing a Lego structure, and improving a miniature golf course.

Time and again, participants chose to additive changes — adding to the existing structure instead of removing something — even when removing something was a more efficient and effective solution.

The researchers asked study participants to stabilize the structure so that it would support the brick above the figurine and analyzed the ways in which participants solved the problem.

The few times a participant group was more likely than not to consider a subtractive change was when they were actively reminded about subtractive changes.

For example, in one experiment, the researchers told the participants that they would get one dollar if they could “stabilize a Lego structure with only one support” (think of a one-legged table). Participants had to modify the existing structure so that it could hold a “memory brick above a figurine.”

Participants could add to the existing structure at a cost of 10 cents per additional block, but that removing blocks from the original structure was free. A control group asked to complete the same task was told about the cost of adding blocks, but not about removing blocks being free. Both groups were told that they could modify the structure however they wanted to.

What they found — Sixty-one percent of the people in the group who received the reminder about removing blocks modified the structure via subtractive changes. The control group that didn’t get this reminder only made subtractive changes 41 percent of the time.

Followup experiments show that people simply don’t think about subtracting when problem-solving. Thus, their default approach to problem-solving was to add to the initial model.

Why this matters — Thinking about adding to a model isn’t inherently bad, Converse says. Sometimes it might be the right way to go.

But thinking only about additions as the solution to a problem is, well, a problem. When we’re confronted with something we can change, we have to start by imagining the different things that we can do.

“It seems that the first question we ask ourselves is ‘what can I add?’ And ‘what can I subtract?’ is not [part of our first reaction],” Converse says. Subtracting something isn’t a harder thing to think of “but you have to think harder to get to it,” he adds.

What their findings suggest “is that there’s a whole class of changes or transformations that we seem to be missing out on,” Adams tells Inverse.

“When we don't think of them, it means we're missing out on many ways that we can make something better,” Adams says.

The practical implications— Adams says more research is needed, but she sees the potential practical implications as twofold.

“First, we're missing this entire class of solutions,” she says. “But also, it has these big implications for sustainability and climate change, none of which we test in these studies. But all of which we see as potential implications of the fact that if people don't think of these things, then here are the ways in which that can be problematic.”

It could also be the solution to jam-packed schedules and endless meetings and bureaucratic red tape — if we can remember that subtractive changes are an option.

What we still don’t know — We still don’t know why we’re so much more likely to consider additive changes than subtractive changes. The researchers hoping to find out through further research.

In the meantime, it’s worth trying to remember that subtractive changes are sometimes a more effective and efficient solution to a problem. Sometimes less really is more.

Abstract: Improving objects, ideas, or situations—whether a designer seeks to advance technology, a writer seeks to strengthen an argument or a manager seeks to encourage desired behavior—requires a mental search for possible changes. We investigated whether people are as likely to consider changes that subtract components from an object, idea, or situation as they are to consider changes that add new components. People typically consider a limited number of promising ideas in order to manage the cognitive burden of searching through all possible ideas, but this can lead them to accept adequate solutions without considering potentially superior alternatives. Here we show that people systematically default to searching for additive transformations, and consequently overlook subtractive transformations. Across eight experiments, participants were less likely to identify advantageous subtractive changes when the task did not (versus did) cue them to consider subtraction, when they had only one opportunity (versus several) to recognize the shortcomings of an additive search strategy or when they were under a higher (versus lower) cognitive load. Defaulting to searches for additive changes may be one reason that people struggle to mitigate overburdened schedules, institutional red tape, and damaging effects on the planet.