SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

3.2 billion-pixel space camera captures largest photo ever

Scientists have designed a camera capable of capturing 3.2 billion-pixel images, and they tried it out on some vegetables.

by Sarah WellsSay "cheese" for one space scientists' newest camera, capable of taking 3.2 billion pixel photographs — the largest single-shot photos ever taken.

Designed to survey the southern sky from Chile's Rubin Observatory for the Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST,) this camera will help us peer back into the universe and answer questions like how galaxies evolved and how theories of dark matter mesh with our reality.

But before this super-sensitive camera hits the big leagues, scientists tested it out on some common, Earthly vegetables.

INVERSE IS COUNTING DOWN THE 20 STORIES THAT MADE US SAY 'WTF' IN 2020. THIS IS NUMBER 4. SEE THE FULL LIST HERE.

When it comes to observing space, the more light your camera or telescope can capture, the better. Using this camera to observe some of the universe's dimmest light, scientists hope to see far back into the cosmological history.

The images taken by the camera are so large that it would take 378 4K ultra-high-definition TV screens to display one of them in full size, and their resolution is so high that you could see a golf ball from about 15 miles away.

But to build a camera this sensitive, scientists at Stanford University's SLAC Laboratory had to construct something a little bigger than your typical smartphone camera.

How it works — The camera they designed is the size of an SUV and has 189 individual light sensors all capable of bringing in 16 megapixels of data, or over 3,000 megapixels in total. For comparison, a typical smartphone is only capable of capturing 16 megapixels.

These 189 sensors are then grouped together in sets of nine to construct "science rafts" that each weighs 20 lbs and cost $3 million.

21 functioning science rafts, plus 4 additional non-imaging rafts, were slotted together to form the final camera. A process that Hannah Pollek, a SLAC mechanical engineer who worked on the project, said was extremely delicate.

"The combination of high stakes and tight tolerances made this project very challenging. But with a versatile team we pretty much nailed it," she said.

The first images taken with the sensors were a test for the camera’s focal plane, whose assembly was completed at SLAC in January.

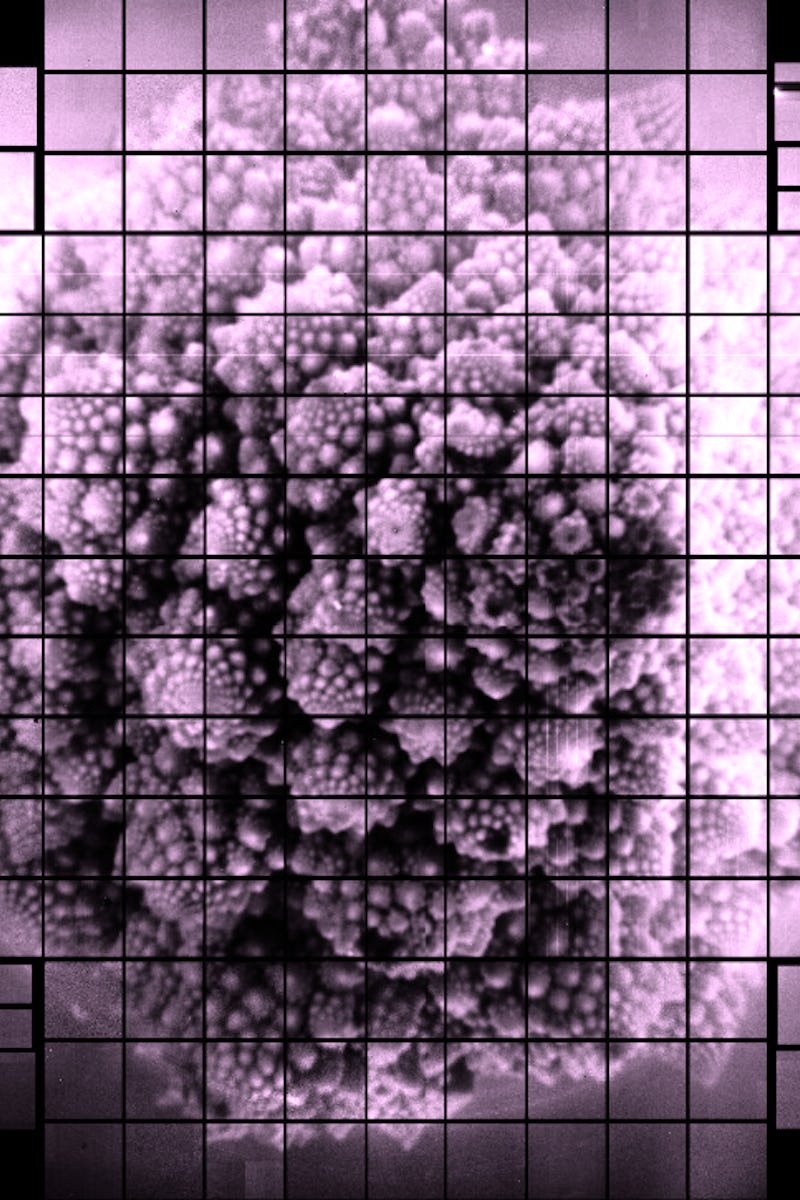

Why it's newsworthy — Before transferring the camera from Northern California to its final destination in Chile, the Stanford team snapped a few test photos using particularly intricate items laying around the lab, including the fractal-like romanesco broccoli, a French engraving of the night sky, and photo of Vera Rubin — the namesake of the observatory conducting the LLST.

These 3200-megapixel images are the largest, single-shot photos ever taken and require nearly 400 4K, ultra-high-def TV screens to be fully displayed.

What's next — This success of these initial photos is an important step toward capturing a better understanding of our universe, said JoAnne Hewett, SLAC’s chief research officer and associate lab director for fundamental physics.

“It’s a milestone that brings us a big step closer to exploring fundamental questions about the universe in ways we haven’t been able to before.”

The camera is slated to make its final move to the Rubin Observatory in 2021.

INVERSE IS COUNTING DOWN THE 20 STORIES THAT MADE US SAY 'WTF' IN 2020. THIS IS NUMBER 4. READ THE ORIGINAL STORY HERE.