Dune is a dark subversion of Star Trek for 1 subtle reason

Let's dig into the Spice melange versus dilithium crystals.

Comparing Dune to the epic dynasties in the faraway galaxy of Star Wars is very tempting. George Lucas probably borrowed the idea of a desert planet from Dune, people working on the new Dune like making comparisons to Star Wars, sometimes good, sometimes bad. But comparing Dune to Star Wars largely ignores the futuristic politics of Frank Herbert's imagined universe. The better comparison is probably Star Trek.

This isn't to say Dune is like Star Trek in tone, but the underpinnings of Dune are similar to the infrastructure of Star Trek, but with far darker implications. The struggle for the natural resource of "the Spice" in Dune is like a version of Star Trek in which the Federation got real about how it actually powers its starships. Let's dig into the Spice melange versus dilithium crystals.

The entire plot of Dune revolves around who controls the rare substance known as Spice, a type of narcotic that gives some people powers to see into the future, and more urgently, "makes space travel possible." All science fiction in which traveling the galaxy is commonplace has some kind of FTL or faster-than-light travel. Sometimes this FTL isn't literally "faster" than light, but instead employs things like "warps" in spacetime or in the case of Dune, "space-folding." Generally speaking, most sci-fi requires you to have a nifty "fuel" or mechanism that allows this to happen. (Star Wars mostly has ignored the need to explain how hyperdrive worked up until 2018's Solo, which retroactively established that a substance called coaxium was integral to traveling through hyperspace.)

Spock and Scotty work on dilithium crystals.

Star Trek's hyper-fuel: dilithium crystals

The starships in Star Trek are nothing like those in either Dune or Star Wars. However, since The Original Series, the franchise has frequently mentioned and depicted dilithium crystals, an essential resource for running warp engines. Scotty often has problems with the dilithium crystals, and occasionally the supply of dilithium crystals can run low.

Early in Star Trek's history, the show couldn't really settle on a name for the various substances that made the Enterprise leap to warp speed. In early episodes, Scotty mentions "lithium" crystals and in "The Devil in the Dark," there's a lot of talk about mining for an element called "pergium." (Though the latter element seems to power things that aren't warp drive, but instead, other energy reactors.) The point is, from TOS to Voyager to Discovery, there are a lot of discussions about dilithium crystals — and their scarcity. Without dilithium, (warp) space travel isn't possible. The dilithium must flow.

Paul, hooked on Spice.

Dune's Spice has parallels with Trek's dilithium

In Dune, the Spice is only found on the planet Arrakis (Dune). As a result, the Mining Guild, the Emperor, and the warring factions House Atreides and House Harkonnen, all are trying to figure out who controls the precious resource. On top of that, the local population of Fremen who actually live on Arrakis, also have a stake in who is taking their Spice and why. The Spice is also produced by large alien sandworms who live in the deep desert, which, vaguely parallels the Horta, the silicon-based "rock monsters" who live in the pergium mines in "Devil in the Dark."

This is about more than space monsters that live near precious resources. In both Dune and Star Trek, the entire political landscape of the galaxy is shaped by the availability and distribution of a substance that makes starships jump around in space. In Dune, the control of that substance is the subject of the first novel. In most of Star Trek, the fact that all ships run on a rare, and tightly controlled substance is mostly an afterthought. Except when it's not.

What if 'Star Trek' was like 'Dune'?

Star Trek sometimes goes Dune

For the most part, Star Trek doesn't talk a lot about the fact its ships operate thanks to the existence of dilithium. But, there are very specific examples that highlight the notion that the Trek universe may not be that different from Dune; it's just a question of narrative focus. In "Mirror, Mirror," the Enterprise crew is desperately trying to convince the peaceful Halkans to let the Federation mine dilithium on their planet. The Halkans tell Captain Kirk that they won't allow any dilithium mining because they know the dilithium is used to power starships that also have destructive powers. Basically, the Halkans tell Kirk to piss off because they are pacifists and they don't want to participate in the Federation's hypocrisy. To his credit, Kirk is cool about this.

Then Kirk, Bones, Scotty, and Uhura are zapped in a parallel dimension — the famous "Mirror Universe"— in which an evil version of the Enterprise is forcibly extracting the dilithium from the peaceful Halkans. On one level, "Mirror, Mirror" is meant to show the differences between the "good" universe and the "bad" universe, but a closer reading of the episode (and subsequent trips to the Mirror Universe) actually just demonstrate how close the line is between a peaceful partnership and outright conquest. For a moment, in "Mirror, Mirror," Star Trek presents a conflict very similar to Dune — a planet with a substance that is desperately needed for spaceflight and an Empire willing to do anything to get that substance.

This idea isn't just limited to Star Trek's mirror universe though. In the Discovery Season 2 episode "An Obol for Charon," Paul Stamets says this motivation to perfect the fungus-powered Spore Drive for the USS Discovery is partially to create a renewable fuel source for Federation starships. Stamets mentions that several planets have had their ecosystems and economies outright ruined by dilithium mining. The basic message of Dune is the same: An obsession with harvesting natural resources at all costs leads to ecological disaster.

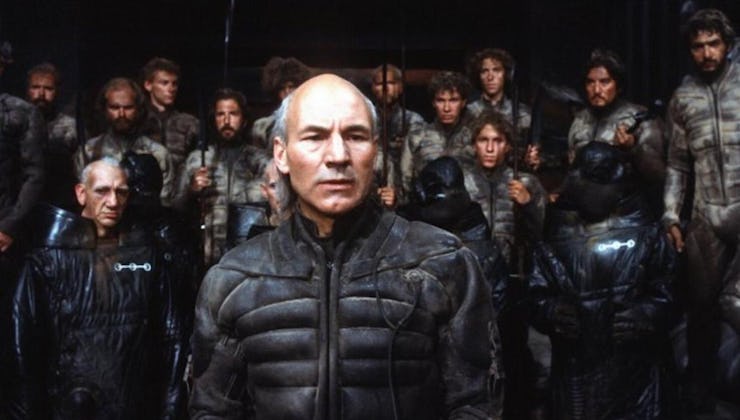

Patrick Stewart as Gurney Halleck in 'Dune' (1984)

Dune is Star Trek without democracy

In theory, the future presented by Dune isn't that different than Star Trek, at least when it comes to the way in which space travel happens. Obviously, the political differences are very different though. Star Trek has a galaxy-wide democracy in the form of the Federation, which trades with other super-powers to broker peace and safety. In Dune, a large Empire exists, which seems to foster a feudal system on a galactic scale.

The wrinkle here is that aspects of the more democratic Trek exist in microcosm in Dune, while the feudal Dune exists in microcosm in various Trek planets. For the most part, the home planet of Paul Atreides, Caladan, seems to be fairly enlightened and egalitarian, even if it seems to be ruled by a Duke. Caladan, is, basically, a smaller version of the Star Trek utopia. Conversely, throughout Star Trek, several planets and cultures are contacted who live on planets who possess the much-needed substance of dilithium. It happens in the TOS episodes "Mirror, Mirror," "Elaan of Troyius," the Voyager episodes "The Muse," "Threshold," among several others.

Star Trek never stays long enough on a planet like Arrakis to see what happens there. The journey of Dune is about what happens to the people who make the starships go on their treks at all. The two universes aren't quite mirror-images of each other. Unless of course, you're high on Spice or you've cracked that mirror by throwing dilithium crystals at it.

Dune (2020) comes to theaters in December 2020.

This article was originally published on