The Hyperloop Could Be a Nationwide Version of the NYC Subway

The race to build the first Hyperloop isn't really a race.

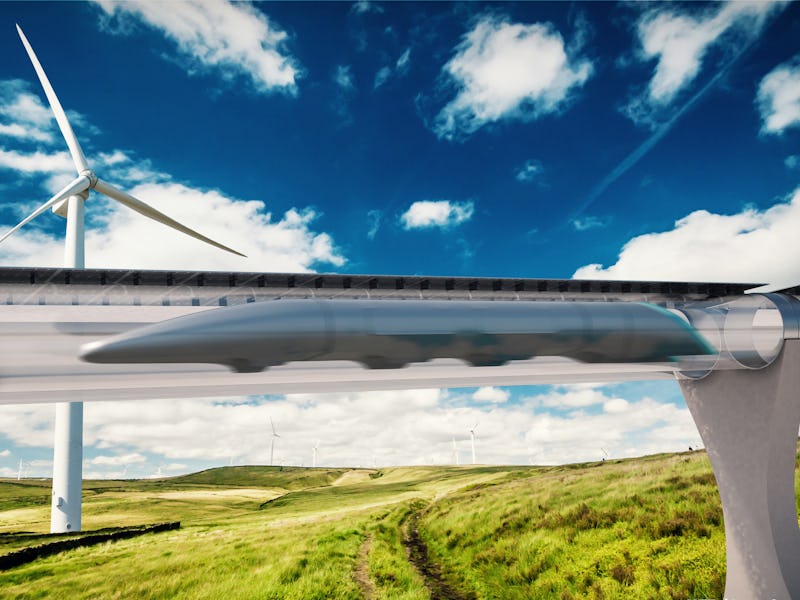

Since the 2013 publication of Elon Musk’s whitepaper on Hyperloop, development of the proposed new technology for high-speed transportation has quickly moved from science fiction into reality. Two major startups are already working to make low pressure tubes capable of shuffling commuter pods back and forth at several hundred miles per hour the future of transportation. And the way these companies and others are going about it could make Hyperloop a kind of subway system for the entire country.

A new feature published Monday by The Wall Street Journal demonstrates how the two companies, Hyperloop Transportation Technologies and Hyperloop Technologies Inc., both with close ties to Elon Musk himself, are vying to produce the first working Hyperloop through pretty contrasting paths. The former, HTT, is working in partnership with Quay Valley, a new community under development that plans to be almost completely solar-powered with low water usage. HTT plans to connect the more than 75,000 residents sitting halfway between San Francisco and Los Angeles to both cities in under a couple hours, tops.

Meanwhile, HTI has yet to develop a prototype or even establish where they want their first test site to be located. Recently, the company partnered up with the Chinese government-owned China Railway International USA, which is currently working on constructing a high speed train between Los Angeles and Las Vegas. This could set the groundwork for HTI to start shooting commuter pods between L.A. and Vegas. If HTI is able to turn Vegas into their own Kitty Hawk, it could turn the project and the city into an entry point for more Chinese companies to establish themselves in the U.S. — which might get the rest of the world to start adopting the technology for their own needs.

The WSJ analogizes the Hyperloop competition to the construction of the New York City subway, in which two separate private companies, using different kinds of train cars, built the nation’s biggest underground rail system during the last century. HTT and HTI could together act like a similar force, building separate Hyperloop networks that coalesce into a sprawling, high speed system of transportation for the entire country.

Of course, there’s a big problem with this kind of future. New York City’s transportation authority, in the present day, must buy two different kinds of subway cars to meet the needs of both track systems. Similarly, two different Hyperloop systems might be unable to cross with one-another, thereby rendering the dreams of transportation efficiency detailed in Musk’s whitepaper impossible.

Perhaps Musk realizes this. After all, he announced in June a plan to host a Hyperloop competition in the summer of 2016. The deadline for submissions passed on November 13, and those teams are now ramping up efforts to create prototypes of passenger pods that could be used in any Hyperloop design. Some of these run on hoverboard technology. Others run by a variety of different methods.

Despite bearing the headline, “The Race To Create Elon’s Musk’s Hyperloop Heats Up,” the WSJ feature paradoxically gives plenty of reason why building the Hyperloop isn’t really a race. For one, the CEO of HTT explicitly says: “I don’t see it as a race.” He means that he doesn’t think his company’s competition are other Hyperloop designers — it’s conventional transportation systems, like planes, trains, and automobiles.

But there’s another dimension to how the Hyperloop race is anything but. Musk’s competition is a way for other players to showcase their ideas and help push everyone forward. When Musk wrote his whitepaper, he essentially gave up the Hyperloop as an idea for the public to run with. It’s no longer the proprietary innovation that could serve to create a transportation giant. It’s a concept that now belongs to the entrepreneurial masses.

Musk’s goal was never to become a dominant force in revolutionary transportation technology — it was to move all of society beyond the stagnant, slow, and inefficient means of today’s technology. Someone will build Hyperloop first, but that doesn’t mean they’ll be the only ones building it. The finish line, in this case, is practically meaningless.

And that’s a good thing. If the United States is going to get its own super-fast, energy-efficient transportation infrastructure that sends people across a thousand miles in an hour, it’s going to need many teams working to accomplish it.