An Earthquake Early Warning System Is Preparing California for the 'Big One'

"Twelve to 15 seconds would be a big deal then!”

When two large earthquakes rocked Southern California this past weekend, residents were reminded of the shifting tectonic plates beneath their feet. Within days, the coverage of the quakes reminded the public of “the Big One,” the proposed major earthquake that some experts think will strike the West Coast in the future.

Fortunately, the United States Geological Survey is in the middle of rolling out a massive early warning system in the area called ShakeAlert.

The 7.1 and 6.4 magnitude quakes over July 4th weekend rattled Ridgecrest, California and surrounding areas, destroying homes. Fortunately, no deaths were reported. The 7.1 quake was bigger than any the area has seen since 1999 and raised fears of the purported Big One, — a major quake along the San Andreas fault that some geologists say is long “overdue.” In the wake of the recent earthquakes, the New York Times, CNN, and the LA Times have raised questions about what might happen when the Big One actually does strike.

"…the US system actually takes earthquake early warning to another level."

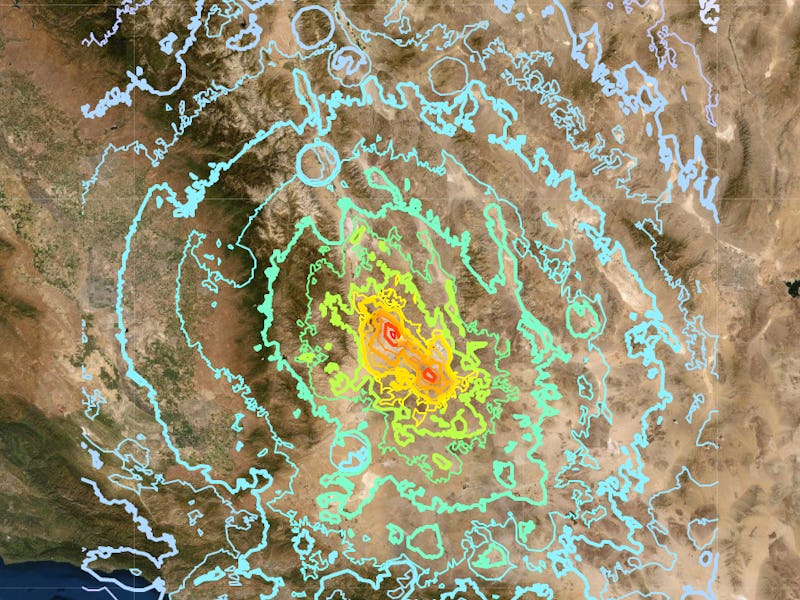

The USGS’s ShakeAlert hopes to prevent anyone from being caught off guard, should such an event arise. When completed, it will be a system of of seismometers — instruments that pick up ground motion — that run through California, Oregon and Washington State. The plan is to have 1,675 stations scattered around the West Coast. Right now, 900 are operational.

The San Andreas fault.

This weekend gave ShakeAlert an unexpected early test before it was even fully up and running. When it’s perfected, USGS representative Robert Michael de Groot tells Inverse, the system “will be most effective for the biggest earthquakes” like the Big One.

Why Early Warning Systems Really Matter

The ShakeAlert system is based on one that’s already operational in Japan. The Japanese system has been online since 2007 and proved its worth in March 2011, when the Tōhoku earthquake, a major tremor (and later, tsunami), was detected off the nation’s shores. The system alerted millions of people to the earthquake’s presence 15 to 20 seconds ahead of schedule.

That may not seem like a lot of time, but in Japan, it made all the difference in what was already a massive tragedy. That warning triggered an automatic emergency braking system on the country’s bullet trains, preventing extensive damage. It’s estimated that 90 percent of people who received that notification were able to take action to protect themselves, according to a 2013 paper.

The earthquake and ensuring tsunami caused serious damage in Japan, though their early warning system still provided a few seconds for some residents to prepare.

A 12- to 15-second warning period would be enough time to take similar precautions for the West Coast’s Big One, explains, Wendy Bohon, Ph.D., a geologist and information officer at the Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology.

“Twelve to 15 seconds could be enough tine to slow down trains, warning taxi’ing airplanes, and automatically shut down or isolate industrial systems,” Bohon tells Inverse.

“You could probably also get to a strong table or other piece of furniture so that you can take protective action like ‘Drop, Cover and Hold on.’ Also, imagine you were in the chair at the dentist getting dental work done. Twelve to 15 seconds would be a big deal then!”

The US system, notes de Groot, bears a great deal of similarity to Japan’s system, though there are some differences too. The American system is being implemented on a far larger scale (it runs the whole West Coast) and will likely involve different algorithms intended to make sense of the input from 1,675 seismometers, he says.

“Design-wise, the approach is very similar to Japan and the US system actually takes earthquake early warning to another level.”

This weekend, ShakeAlert got an early taste of the big time before the project was even completed.

So, How Did ShakeAlert Do This Weekend?

Once one of ShakeAlert’s 1,675 proposed seismometers detects a tremor, that information will be transmitted to an earthquake alert center that then passes the information on to people’s phones via a mobile app, like ShakeAlert LA, recently rolled out in Los Angeles.

But people will only get a notification if the quake hits two crucial thresholds: It has to be a magnitude five or above, and it must have a local intensity rating of a four out of ten or higher, measured on the Modified Mercalli Intensity Scale (MMI) scale. A four on the MMI scale is enough for people indoors to feel shaking or for dishes, windows or doors to be disturbed.

This weekend, the seismometers affiliated with ShakeAlert did exactly what they were supposed to do, says de Groot. But the ensuing events also revealed two of ShakeAlert’s early growing pains.

"12-15 seconds could be enough tine to slow down trains, warning taxiing airplanes, and automatically shut down or isolate industrial systems.”

People closer to the epicenter of the quake received notifications on their from ShakeAlert, but those over 100 miles away in Los Angeles proper did not because the MMI intensity was not high enough in their area. The absence of a push notification led some to condemn the system as faulty, even though it performed the way it was supposed to. Now, L.A. is lowering its MMI threshold and will send push notifications for lower levels of intensity.

The past weekend also revealed how long it takes for ShakeAlert to decide whether to issue an alert in the first place. According to de Groot, it took eight seconds from initial detection to the moment an alert got sent out. He hopes it will do slightly better in the future.

“My point is is that there’s still some work to be done on the delivery side, where messages are being delivered on our behalf. Some of those times are longer than they’d like them to be,” he says.

Time crunches aside, the system did work according to plan. But they’re looking to get even more specific in preparation for the Big One.

And if we have learned anything from Japan, there’s good reason to make every second count.