Japan's Gender Gap for People Who Live to Be Over 100 Is Getting Bigger

But the overall gender gap in life expectancy is shrinking.

Misao Okawa, once the world’s oldest woman, didn’t start using a wheelchair until she was 110 years old. The supercentenarian, who was born in Osaka, Japan, died a month after her 117th birthday, and while she was certainly unique in her longevity, she was also part of a fast-growing demographic of people in Japan: Women who live over 100 years.

A report from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare shows there are 69,785 Japanese people older than 100 as of September, an increase of 4,093 since 2017. The Japan Times reported on Friday that this year is the 48th consecutive year that the number of people in Japan over 100 has gone up. It also represents a seven-fold increase over 20 years ago.

Oh yeah, and 88.1 percent of these centenarians are women.

While Okawa’s case and those of the thousands of others like her are fascinating — not to mention inspiring to those for whom old age is an aspiration — it begs several questions: Why are the oldest residents of Japan almost all women? And more broadly, how long can a person live?

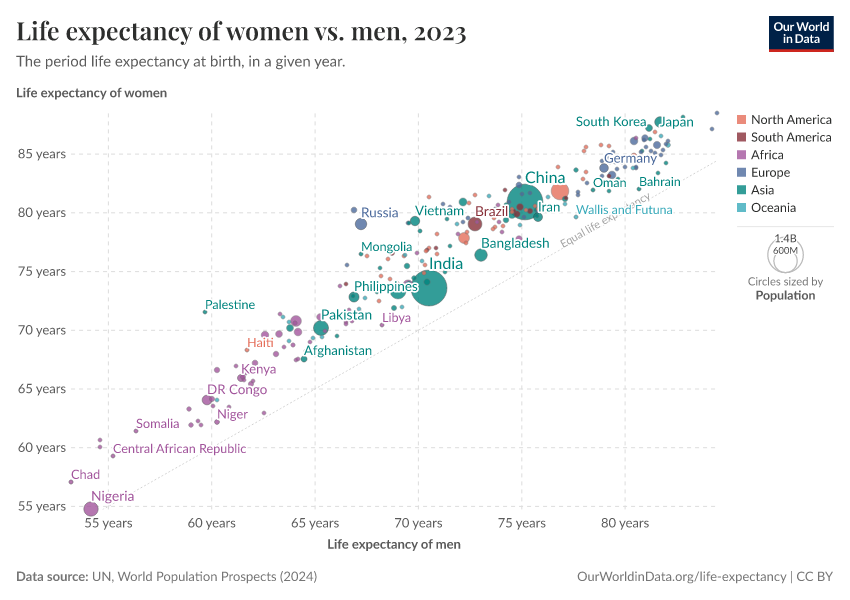

Scientists aren't sure of the upper limit of the human lifespan, but they've found a clear disparity between men and women all around the world.

Let’s look at the second question first since it’s the simplest one to answer: Scientists can’t agree on the upper limits of the human lifespan. Even when researchers have sought to find an upper limit, their statistical models still don’t account for people like Okawa.

There does seem to be some limit, as determined by cell function. In a PNAS paper published in October 2017, researchers argued that the tension between a cell’s need to survive and its mission to support the organism it belongs to will ultimately result in death, whether sooner or later. So even though we don’t know what the maximum human lifespan is, we do know that human lifespans are finite.

But Why Do Japanese Women Live Longer Than Men?

Although a comprehensive answer is tough to nail down here too, luckily, scientists have more concrete data behind it. One thing is clear: On average, women all over the world live longer than men. Even as lifespans for both men and women have increased over the last century, women in all countries for which the World Health Organization and United Nations collect data still live longer than men.

In Japan, this life expectancy gender gap is especially pronounced. According to 2015 data from the WHO, women in Japan live an average of 86.8 years, longer than women in any other WHO member country. But Japanese men live an average of only 80.5 years, according to the same dataset, putting them in sixth place globally (tied with Italy).

In a 2013 paper in the journal Geriatrics & Gerontology International, a team of researchers sought to address Japan’s gender gap in life expectancy. The study’s authors note that the gap in life expectancy between men and women in Japan was the largest — seven years — in 2004. After that point, it slowly declined to 6.75 years in 2010, which was the last year of their dataset. WHO data show that this gap has continued to close, coming down to 6.3 years in 2015. Inverse’s analysis of the data finds that Japan’s gender gap in life expectancy was only the 44th highest in the world in 2015, with Russia at number one with 11.6 years.

Why Women Live Longer Than Men in Japan

According to that 2013 paper, disease-specific mortality ratios can explain a significant portion of Japan’s gender gap in life expectancy. Specifically, the paper’s authors found that men were at higher risk for chronic bronchitis and emphysema, suicide, diseases of the liver, and cancer. On a somewhat grim note, they found that the increasing popularity of cigarette smoking among women in recent years could be one of the factors closing the gender gap.

But despite the fact that the gender gap in the Japanese population’s overall life expectancy is shrinking, the gap in the centenarian population appears to be growing. This year’s numbers provide an illustration of that. The number of centenarian men increased by 1.7 percent since 2017, up from 8,192 to 8,331. This increase sounds pretty healthy until you look at the number of centenarian women, which went up by 3.1 percent since 2017, from 59,579 to 61,454.

So even though smoking may be catching up to Japanese women overall, it seems that Japanese men are falling behind when it comes to old-old age, and it’s hard to say why.