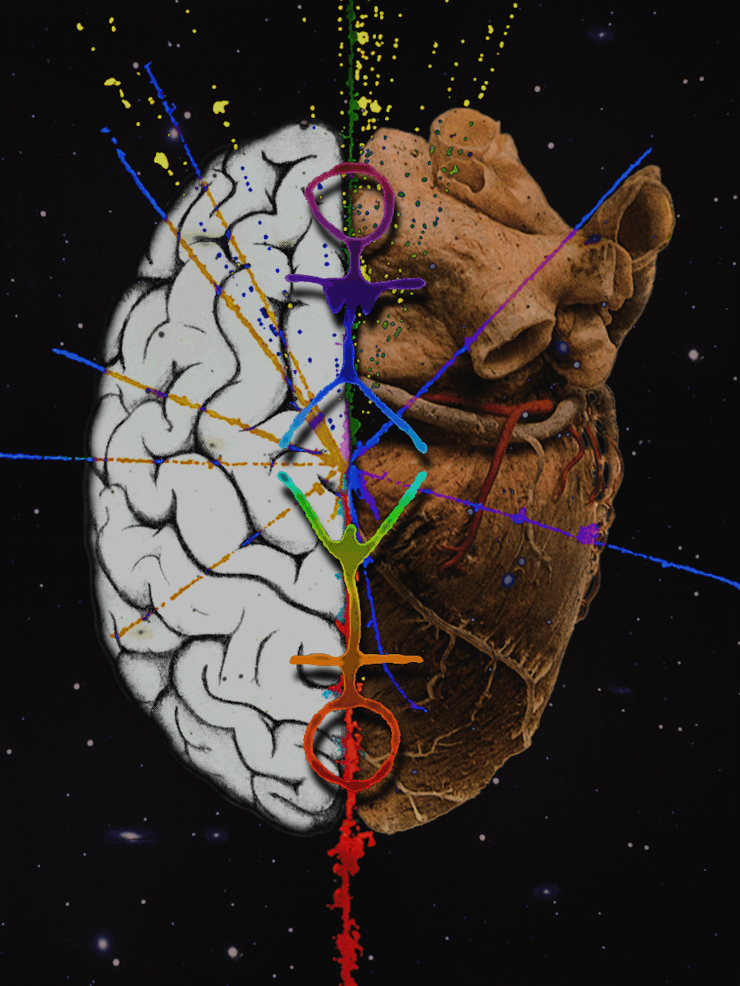

Why We Physically Feel Love and Heartbreak

It's like a chemical explosion inside our brains and our bodies.

Hearts pump blood, but we associate hearts with love and heartbreak. In fact, that term alone — heartbreak, or its sister term, heartache — points to the pain of relationships on your heart. But we all know that a muscle in your body can’t feel psychological pain or pleasure, right?

Well, kind of. The whole process of falling head over heels in love with another human and breaking up with them actually has a lot more to do with your heart and brain than you might expect.

When two people have the hots for each other, their brains experience a flood of chemical changes, rewiring them entirely. A 2017 study published in Trends in Cognitive Sciences evaluated how and why these cranial chemical changes occur by comparing multiple animal species to humans. The study concluded that levels of dopamine and oxytocin (both “feel good” chemicals) increase in the human brain when it forms an attachment with someone. We get so excited about a significant other that our brains go haywire and lust for more. Over time, this begins to form what is called biobehavioral synchrony for the couple: Both people start to act similarly loopy because they’re drugged up on dopamine. Likewise, oxytocin (also called the love hormone) increases with emotional and physical connection, especially during sex or when cuddling. Increased levels of oxytocin lead to feelings of stability and trust; we end up wanting more of those warm fuzzy feelings, more oxytocin is released, and a chemical cycle goes on.

Love also induces adrenaline in the brain. When a person is in love, they might trip up on words, sweat uncontrollably, and have heart palpitations. That flutter in your heart when you see someone might not be love at first sight, but it certainly is some biochemistry action, according to a 1989 study published in the Journal of Research in Personality. Researchers got two participants to gaze at each other without breaking eye contact for two minutes. Of the 96 participants, 72 reported that the locked gaze made them feel much more passionate about the person across from them. This is because attraction increases when a person feels recognized, and with attraction comes passion.

Loving someone feels really good. But, when a relationship goes astray, those feel-good chemicals all nosedive and wreak havoc on your love-high body. People can experience extreme depression when they are detached from their significant other. Loss of appetite, insomnia, increased stress, and problems focusing are just some of the issues we experience when we lose that special someone. There’s a reason why these symptoms are similar to those of someone who’s going through withdrawal: A brokenhearted person is going through one, too. In rare cases, some people may actually die of a broken heart.

There is a scientific term for this: takotsubo (or stress) cardiomyopathy. It’s a newly recognized disease that causes the left ventricle of the heart to weaken because of stress. One of the most notable studies on patients with broken heart syndrome was published in the British Medical Journal in 1969. The study evaluated 4,486 male widowers who were over the age of 55 years and followed up with them for nine years. In the first six months, 213 of the participants died of cardiovascular disease — 40 percent lower than the average life expectancy rate for non-widowed men of the same age. While researchers can’t conclude for sure that patients died of a broken heart, later studies have suggested that dying of a broken heart is a very real, albeit rare, thing.

A 2003 study from the journal Science ran a series of MRIs on patients that went one step further by studying people who had experienced social loss. What they concluded was that the same part of the brain that tells your body it is in physical pain is affected by losing someone you love. So while your heart is probably physically not shattering into a million pieces, it’s true: Your heart is breaking — and it hurts.