Is Planet Nine a Rogue Planet?

Rogue planets just had their unfortunate introduction to the public consciousness via an especially silly conspiracy theory involving a collision and the subsequent end of the world. Let us not allow that to bury the actual new research coming forth about them, because that’s what’s really worth your time.

Researchers testing whether a much-mythologized object called Planet Nine might indeed be a captured rogue planet found it certainly looks like one. They also performed simulations of various different kinds of rogue encounters with our solar system; they found that if the rogue had a mass equal to or greater than that of Jupiter, it could subsequently leave a physical impact on the configuration of the entire system. James Vesper of New Mexico State University presented the research Friday at the 229th American Astronomical Science meeting in Grapevine, Texas.

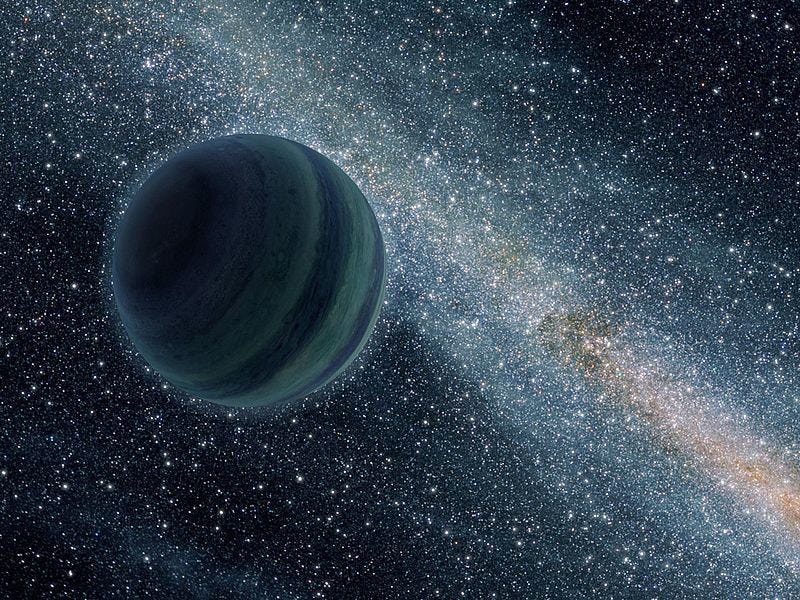

We can easily picture the stars that don’t have planets, but it’s a bit odd to imagine in inverse (sorry) — free-floating planets rolling around in space, not tethered by any kind of regular orbit, either because they’ve escaped their original host star or because they never formed around one to begin with. Those planets are rogue planets, and they’re often prone to being “captured” by a new star when they wander into its system.

Vesper said their data showed 60 percent of all rogue encounters being “slingshotted” into the galaxy — they come in close to the sun and then shoot right back out. About ten percent of these encounters take one or more planets out with them. If two or more planets are knocked out — but the rogue is captured — Vesper refers to the exchange as a “kick and stay.”

Suffice it to say rogue planets can mess things up in a variety of ways.

Planet Nine, the newly minted ninth planet in our solar system, is roughly ten times the size of the Earth and has been notoriously difficult to observe directly.

There are scores of rogue planets in our galaxy — possibly numbering in the billions — and a handful relatively close to our own solar system. There are enough to possibly provide an explanation for some of the dark matter in the Milky Way’s disc, and they actually outnumber stars.