Conservative Genes Stoke Fears of "Small" Syrians

Conservatives perceive refugees to be smaller and more dangerous than they are, but that's no one's fault.

Earlier this year, evolutionary psychologist Colin Holbrook demonstrated that when white people imagine encountering a black man — on a sidewalk, at a corporate event, or in his home — their brain performs a strange magnification. Black men appear large and more threatening to white people — even if they are neither of those things and the white people in question aren’t racists. This gave Holbrook pause, but not enough to stop him from proceeding with another, news-pegged experiment on the perception of Syrians by non-Syrians. What he found may seem unexpected and in defiance of all logic: Where Holbrook had previously found a strong correlation between size and threat perception in regards to minority populations, he discovered that conservatives thought Syrians were small and threatening.

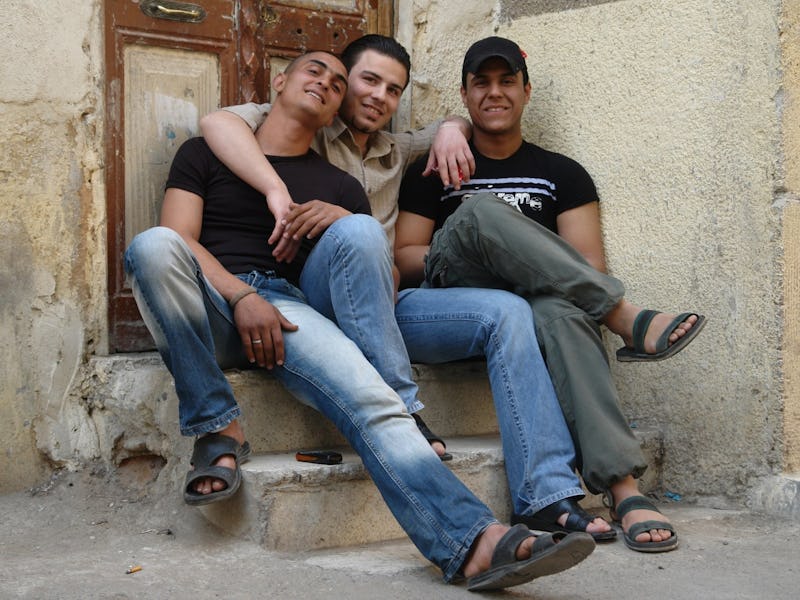

Confounding as the study’s results were, the experiment was relatively simple. Holbrook told the story of several Syrian refugees to five hundred subjects via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk system. Respondents were asked to estimate the size of a refugee named Hassan, who had not been described physically. They were also asked to guess the size of a racially ambiguous man named James who had been displaced from his job rather than his country. Both James and Hassan are described as waking up on a Saturday morning to brush their teeth, looking for a job, and spending the evening with friends — Hassan with fellow refugees trying to cross the border, James with fellow job seekers. The research subjects were also asked about their own political ideologies.

From these questions emerged a curious pattern: Conservatives associated Hassan — and therefore refugees — with terrorism to a far greater extent than did liberals. They were willing to engage in elevated police measures to close borders and secretly spy on refugees. “In fact, the effect of conservatism on perceiving the refugee as physically small and weak was statistically explained by confidence in the ability to use force to fight terrorism,” Holbrook said.

Sociologically, the theory of a perceived threat seeming bigger than they actually are makes sense. After all, legislation, cops, and most Americans seem to treat black and Latino men as threats. What’s really weird about the particular pattern found in this study — Holbrook dubs it the “Gulliver Effect,” after the Lilliputians who terrorize Jonathan Swift’s titular character — is the fact that it can run in reverse.

This could make evolutionary sense, though. Holbrook defines conservatives and liberals not necessarily by where they land on the political spectrum but their worldviews. Conservatives see threats they must destroy, something that warrants an aggressive response — more military force, less diplomacy, “more stick than carrot.” Liberals are, predictably, the opposite in how they perceive threats: more cautious, willing to negotiate and tread carefully before engaging.

Lest you think the conservative versus liberal structure of thought seems to be something that is uniquely American, Holbrook reminds us it’s not. Along with his collaborators, he expanded the experiment to Spain, which has welcomed many thousands of refugees more than the U.S. The timing of this study was especially pertinent, taking place in the days immediately following the March Brussels airport terrorist attacks (a mere 980 miles away from Madrid). The exact makeup of what makes a Spanish liberal and conservative differ from what makes an American one, but the basic threat perception remains the same across the board: Conservatives are loyal to an ingroup when it comes to scarce stuff, liberals are focused on distribution of resources. And Syrian refugees — or any other refugees or minority groups, for that matter — are a direct threat to those scarce resources.

Which brings to mind a very important, almost too-bizarre-but-obvious question: Is a person’s political ideology genetically ingrained within them?

Holbrook says probably — though he quickly adds that the extent to which this is the case has not been tested yet. Political ideology, as Holbrook defines it, harkens back to how we as humans view threats in our immediate environment, whether they be animals or other groups. It’s a basic part of our DNA playing out in a modern setting in a totally familiar — yet also unfamiliar — context of minority groups in an age of globalization. Add to that a political environment which is inherently fearful of the unknown (regardless of if you identify as conservative or liberal), and Holbrook argues that one thing is for certain: You’re genetically predisposed to be wary of threats and respond in some fashion, but society ultimately shapes how you perceive these threats — whether it be through fake news or outright racism.

“None of our ancestors ever had to think about the plight of millions of refugees,” Holbrook said. “We have shown that both liberal and conservative political orientations shape reasoning about both terrorism and the refugee crisis. Ultimately, our research is about more than the link between political orientation, threat-perception, and support for aggression. It is part of a larger program in evolutionary psychology intended to help identify blind spots within our minds that warp our ability to treat others in a rational way.”