Even If Human Lifespan Skyrockets, We May Not Need Mars

As humans begin to live longer, the ideas that govern our lives -- family, career, death -- will change.

Futurists have promised humanity two lifelines: radical life extension and space colonization. At first glance, these two contingencies seem to depend on each other. Earth feels more and more overcrowded each year (current population: 7.4 billion). If you imagine that a significant percentage of people live significantly longer lives — 150 years or so — then the population will reach new heights. It’d therefore be great if, around the same time humans become quasi-immortal, we also established colonies on other planets.

But Max More, who’s responsible for the modern definition of transhumanism, and who is president and CEO of Alcor, the cryonics laboratory, tells Inverse that we can have the former without the latter.

If we can mitigate or even stop the effects of aging, the implications will be far-reaching. At first, mere prolongation of life — if that’s even possible — might not seem like a major accomplishment. People born into that world would just expect a long life, and, with all diseases eradicated, they’d only know of sickness from history.

As humans begin to live longer, the ideas that govern our lives — family, career, death — will change. But it also seems reasonable to think that, as more and more humans come to (or continue to) exist, our planet will continue to devolve. One might think it best for us to get at least some of our eggs out of the current, bloated basket.

Dippin' out.

But More thinks it’s unlikely for us to send humans, in their current forms, deep into space. If we can figure out how to upload our minds, and eventually, virtually travel to distant planets, then that’s another story. But even if we do not, More isn’t too worried about overpopulation. In fact, he’s worried about the opposite.

“It seems probably impractical to send people out in basically ape bodies into interstellar space,” More tells Inverse. “It’s incredibly expensive to have an interplanetary system like that.”

Uploading, the theoretical ability to disembody consciousness, and store a mind in the cloud — despite its questionable philosophical implications — would be the obvious solution.

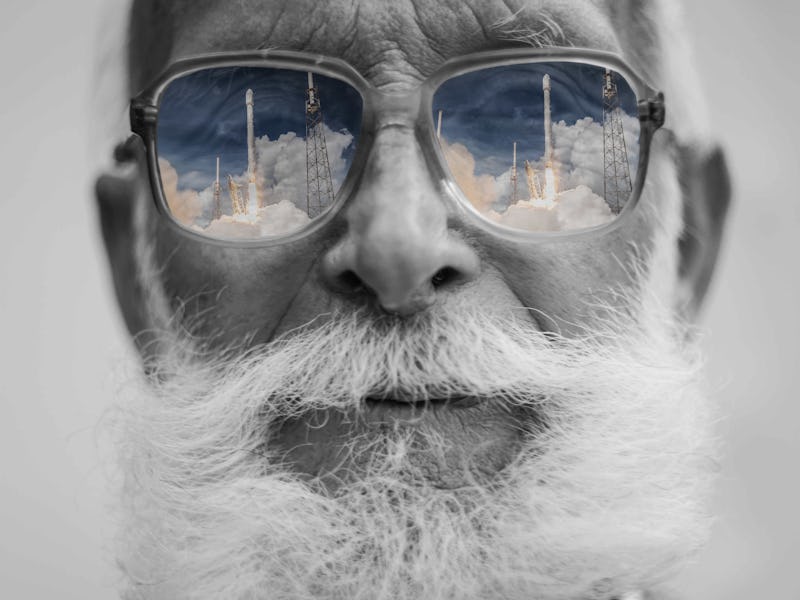

“Send a very small rocket, with data and a nanorobot that can construct bodies, and other things, on the other end. We’re not sending a huge spacecraft interstellar distances — it’s probably just completely impractical, and if we did we’d have to use something like cryonics. It would take a very, very long time to get there.” (Sorry, Elon Musk.)

Max More.

But even if we can live indefinitely, we may not need to find new habitats. Overpopulation depends on procreation more than it depends on life extension, More says. “Childbirth is the exponent in the equation, whereas the length of your life is more the constant. If nobody had any more children, and nobody died, the population wouldn’t grow or shrink.”

However, for the next century, More thinks we should be more wary of underpopulation. “Even the United Nations, which has consistently overestimated population growth, is saying by 2060 or 2080, global population will have stopped growing, and will start shrinking.”

“We should actually be worrying about underpopulation.”

This projected population decline is worrisome to More: “There’s no bottom to that, really. It could go down to zero, in fact. Already, about 38 percent of the territories in the world have static or declining population, or are on the verge of contracting. All of Eastern Europe is shrinking, all of Russia. Pretty much all of Western Europe has either stopped growing or is on the verge of stopping. Germany’s already shrinking. Of course Japan is rapidly shrinking. In the U.S. it’s a little bit different, but that’s clearly the trend.”

Overpopulation is “a very 1960s kind of concern,” More believes. Underpopulation is the new fear, and it’s based in fact (growth rate being the relevant statistic). Precarious voyages to Mars may not be too prudent.

“We don’t have good experience with shrinking populations,” More says. “So having people live longer, healthy lives actually could help us in that event.”

While these two ambitions do not depend on each other, we can still hope that Musk, with his various SpaceX dreams, gets us to Mars. But the trip would be a whole lot sweeter if the settlers could count on living long enough to make it back home.