When Cyborgs and Christians Compromise

The religious right is coming to terms with Transhumanism. But the faithful still worry about the future of humanity.

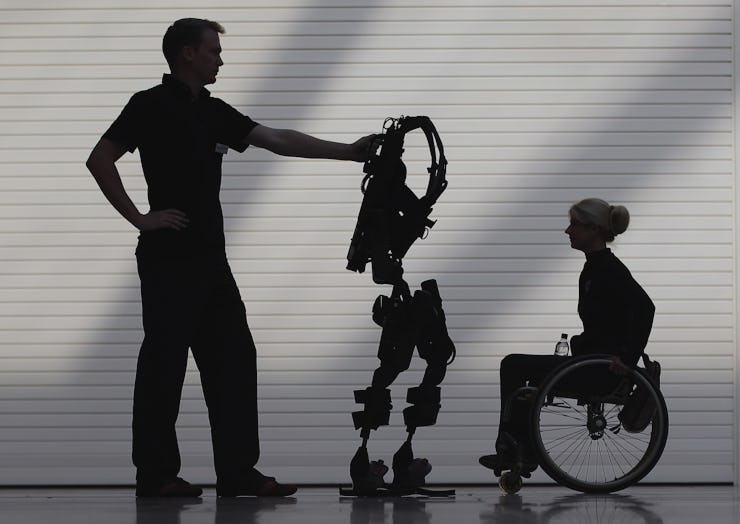

In August, a paraplegic man was brought onto the stage at the Human x Design Conference in New York City, a gathering of the world’s leaders in transhumanist thought. The man could not walk, but he wore a curious exoskeleton, thin and delicate. With a mechanical whirr, the man stood up and strode defiantly across the stage.

“Everyone’s breath was taken away,” E. Christian Brugger, a professor of philosophy and ethics at Denver’s St. John Vianney Theological Seminary who attended the conference, told Inverse. Brugger was at the meeting representing a conservative school of thought — one that would seem to be at odds with the transhumanist project, premised as it is on the idea of re-invention. Brugger is well aware that religion has not historically met technological and scientific adjustments to the definition of humanity with open arms, but says that a walking paraplegic illustrates how the conversation around transhumanism could potentially end in mutual understanding.

Still, there’s a lot of ground to cover.

A recent Pew Research Center study surveyed over 4,700 Americans on their thoughts about using biotech to enhance human abilities, and the results revealed a country wracked with skepticism and fear. Some 68 percent of adults were “worried about” using gene editing to reduce babies’ risk of disease, 69 percent felt similarly about brain chips to improve cognitive abilities, and 63 percent felt the same about using synthetic blood to improve their physical abilities.

And perhaps most unsurprisingly, the religion-science divide was highlighted in Pew’s analysis. More religious Americans were more likely to respond negatively to human enhancement, an intervention they were likely to classify as “meddling with nature.”

Brugger is sympathetic not only to that idea, but also to the notion that radical solutions can be good. He identifies the intersection of the religious right’s core values with transhumanism as the “therapeutic use of biotech.” He’s keenly aware that transhumanists like to talk about abstract ideas that unnerve observant Christians while actually creating technologies that don’t.

“Perhaps that should be the starting point for the conversation, rather than starting with uploading our minds into the cloud completely so that we’re in a disembodied world,” he says.

Neil Harbisson, a prominent transhumanist that spoke at the Human x Design Conference, wears an implant that lets him hear color.

Issues like abortion, drug use, gene editing, and cloning have widened the schism often apparent between the scientific and religious communities. The accusation leveled against scientists by those who object to their work is often that they are “playing God,” pushing the limits of what parts of our bodies are morally acceptable for us to manipulate.

“In the imperative ‘If we can do it, then we should do it,’ they hear a whisper of the original temptation,” Brugger says of religious Luddites. “Do it, and you’ll be like God.”

Religious people, he explains, are concerned about a future in which humans become preoccupied with metamorphosing into “something more than human.” And to be fair, their concerns about transhumanism, a movement founded on the idea of superhumanity, are understandable. It’s easy to see that figures like Zoltan Istvan, a third-party presidential candidate who travels across the country in a coffin-shaped bus campaigning for infinite life extension, and Neil Harbisson, a colorblind “cyborg activist,” who has a device implanted into his skull that allows him to hear color, play the false prophet well. If their existentially ambitious and ethically ambiguous projects are the future of the transhumanist movement, reconciliation with the religious right seems incredibly unlikely.

E. Christian Brugger, a Christian moral philosopher and ethicist, believes transhumanism and religion can be reconciled if their goals can be aligned.

But it’s not impossible to imagine a future where transhumanism and religion can co-exist, argues Micah Redding, the executive director of the Christian Transhumanist Association, who believes that it isn’t the technology itself that’s at odds with the religious set but the reasons we give for developing it. “Life extension is simply the process of healing the human body,” Redding told Inverse. “Anyone who supports medicine should, in theory, be able to support radical life extension.”

After all, we’ve always used technology to improve our quality and length of life. That’s what tools are. The Bible doesn’t urge us to ignore our own helplessness — to the contrary.

“We wear glasses, we wear contacts, we get heart implants, we get dental implants, all of these things have been going on for generations,” Redding says, noting that none of these technologies have ever been considered to be at odds with Christianity. Why, then, should we treat smart blood — which promises to improve our physiological abilities — or a computer chip — which could improve our intelligence — any differently?

Redding argues that extending life is a Biblical mandate, commanded by the call to imitate a God that believes life is good. “Just as God creates and cultivates life, he wants us to create and cultivate life,” Redding says.

Transhumanists have reason to believe we are on the cusp of the movement’s breakthrough moment: CRISPR-based gene editing has the potential to create a stronger, smarter “Homo futurus”; cryonics holds the promise of frozen immortality; science is beginning to fold in robotics and artificial intelligence to improve our everyday activities. For followers of Redding’s particular brand of Christianity, it would be morally irresponsible not to use those tools.

The crowd’s unanimously positive response to the defiantly mobile paralytic at the Human x Design Conference was proof that human augmentation can bring about a sense of contentment that we’re all morally okay with. A paralyzed man, fused to an exoskeleton, who regains the ability to walk shouldn’t be an example of our defiance of Gods omnipotence or our brazen audacity to do things because we can. If we want to live in a world in which God-fearing and longevity-embracing can live together, he should be viewed, quite simply, as a man who was formerly sick and now is not.