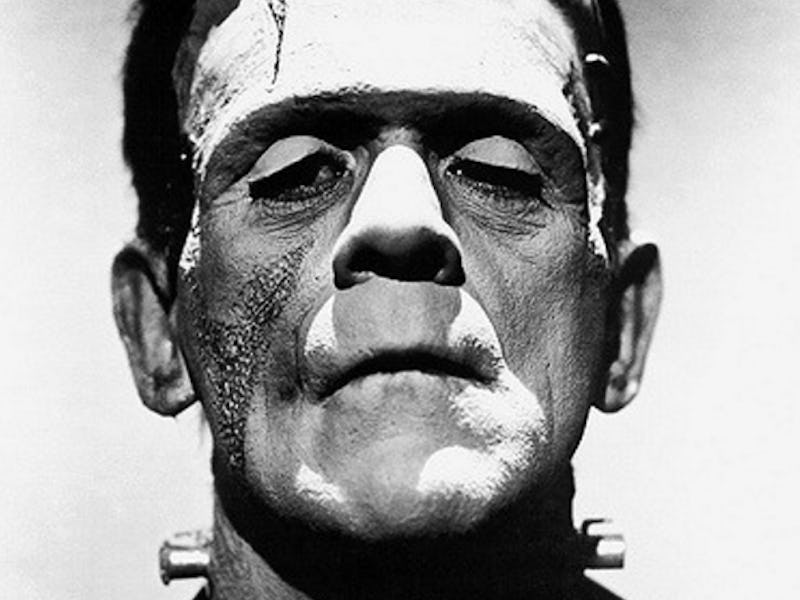

Victor Frankenstein's Monster Just Turned 200 and Became Relevant Again

The ability to resurrect the dead, an obsession of early 18th-century scientists, is starting to seem like a possibility again.

On June 1816, a quartet of young British writers watched a storm roll in over Switzerland’s Lake Geneva from the windows of the Villa Diodati. Stuck inside, they debated what to do and hit upon a plan, they would each write a horror story in an attempt to terrify the others.

Lord George Byron, hotshot poet and possible incest enthusiast, scribbled out the tale of the dangerous Ivan Mazepa while his doctor, John Polidori, worked on the story of the bloodthirsty Lord Ruthven. Both of these works were proto-vampire tales that would be emulated for the next two centuries. Meanwhile, Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, soon to be both 20 years old and Mrs. Percey Byshe Shelley, wrote “Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus.”

Her future husband just swanned around, as was his want.

It’s debated when exactly Shelley shared her story of a corpse reanimated to life (historians typically place the date somewhere between June 16 and June 19) but what we do know is that Shelley had major writer’s block until she encountered the vision of Victor Frankenstein and his creation in a dream. In a preface to the third edition of Frankenstein Shelley writes:

“I saw — with shut eyes, but acute mental vision — I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion. Frightful must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavor to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world. His success would terrify the artist; he would rush away from his odious handywork, horror-stricken.”

To Shelley, Frankenstein was a monster of her own creation — an object of fantasy and a warning tale. But doctors in Shelley’s time were already experimenting with the idea of bring life back to the dead: Brutal experiments that serve as the morbid lineage to the medical reanimation studies attempted today. How close have we come to bringing back the dead since Shelley had a nightmare in 1816? Closer than the 18-year old woman could had ever imagined.

An illustration in the 1831 edition of *Frankenstein*.

Shelley might have been subconsciously inspired by the work of the Society for the Recovery of Persons Apparently Drowned, a group set up by two British doctors in 1774. The goal of the group was to teach people how to resuscitate others — Shelley’s own mother, the writer and pioneer feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, was resuscitated after her attempted suicide in the Thames. According to the British Library, the idea that there were two kinds of death — one incomplete and another absolute — became to be a popular one at the time. Death started to seem less absolute.

However, the fad turned from focusing on resuscitation towards something distinctly more to Frankenstein’s style. Galvanism, which Shelley had credited as an influence on her story, started when Luigi Galvani realized that he sparked a dead frog’s leg with electricity, it would twitch — a momentary reanimation that Galvani thought meant that life really did come back for a few seconds (he was wrong). Giovanni Aldini, his nephew, took this even further: In 1803 he began experimenting on dead people, electrocuting the heads of dead humans, making their jaws clench and eyes open. He started touring Europe, putting on demonstrations of shocking rabbits, sheep, dogs, and oxen — often killing the animal and then shocking it “back to life” for the crowd. This act inspired other “doctors” at the time — like French physician Jean Baptiste who attempted to resuscitate severed heads by drilling holes in the skull, inserting needles into the brain, and filling it up with blood.

“At the turn of the nineteenth century quite a few people were in the business of bringing the dead back to life,” writes Frances Larson in the excellently titled “Severed: A History of Heads Lost and Heads Found. “Scientists were still trying to elicit some kind of response from severed heads at the end of nineteenth century by pinching, prodding, burning and cutting heads in the minutes after death.”

A cartoon commenting on galvanism in 1836.

Flash forward to the 20th century and medical attempts to bring back the dead became distinctly more medical. Yet, within carefully chronicled trials of experimentation that go with modern medicine, is still the spirit of the galvanism-practicing “doctors” who believed that the dead don’t have to stay that way. It increasingly became understood that people can also be like Schröndingers cat — simultaneously alive and dead.

“We’ve all been brought up to think death is an absolute moment — when you die you can’t come back,” Sam Parnia, a doctor at State University of New York in Stony Brook, told the BBC. “It used to be correct, but now with the basic discovery of CPR we’ve come to understand that the cells inside your body don’t become irreversibly ‘dead’ for hours after you’ve ‘died’…. Even after you’ve become a cadaver, you’re still retrievable.”

CPR was invented by Dr. Peter Safar in the 1950s. After sedating and momentarily paralyzing volunteers, he would tilt a subject’s head back and push the jaw forward, allowing him to find an effective airway opening. Mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, he found, was much more effective that previous techniques like applying pressure to the chest. After his own daughter fell into an asthma-induced coma and died, Safar became convinced that all people should know how to resuscitate. In 1967 he helped implement the first ambulance service with volunteers and physicians trained in CPR.

In the vein of walking the line between life and death: Doctors Peter Rhee and Samuel Tisherman made news in 2014 when they announced they developed a technique to stall death long enough to bring an individual back.

“We are suspending life, but we don’t like to call it suspended animation because it sounds like science fiction,” Tisherman told New Scientist. “So we call it emergency preservation and resuscitation.”

But suspended animation is the name that has stuck and what they do does sound like it’s straight from a movie. First, all of a patient’s blood is replaced with a cold saline solution that cools the body enough to stop all cellular activity — they’re in a state where they’re not quite alive but also not dead. This gives doctors a window of time to fix the injury. Then the body is re-pumped with blood, warmed up, and the heart begins to beat again when the body reaches 30 degrees Celsius.

Students practice CPR with a dummy.

Today we’re closer than ever to mimicking the abilities of Victor Frankenstein. In May 2016 it was announced that the United States government gave the go to a “death reversal” projected spearheaded by two private biotech companies. Brain death is considered death under U.S. law.

Officially titled the Reanima project, the goal is to use a “range of existing medical techniques” to get brains to repair and regenerate after being declared dead. Scientists are currently working with 20 brain-dead subjects in India, and using stem cell and peptide injections, lasers, and nerve stimulation to prompt the brain to have a physical response. If it proves true that medical techniques can restore consciousness, then these scientists will prove that brain death is a curable illness.

And where science is lacking, sometimes (in the very rare occasion) your own body can suffice. The Lazarous phenomenon was first described in 1982 and has only been chronicled in medical journals 38 times since. It’s defined as “unassisted return of spontaneous circulation after cessation of cardiopulmonary resuscitation.” In other words, the patient is resurrected after physicians have given up on saving them. Sometimes, for the lucky few, life can be restored without a Victor Frankenstein.