Facebook Seeks Global 5G Networks With Terragraph and Project ARIES

Wednesday's keynote at Facebook's F8 brought tidings from a faster future.

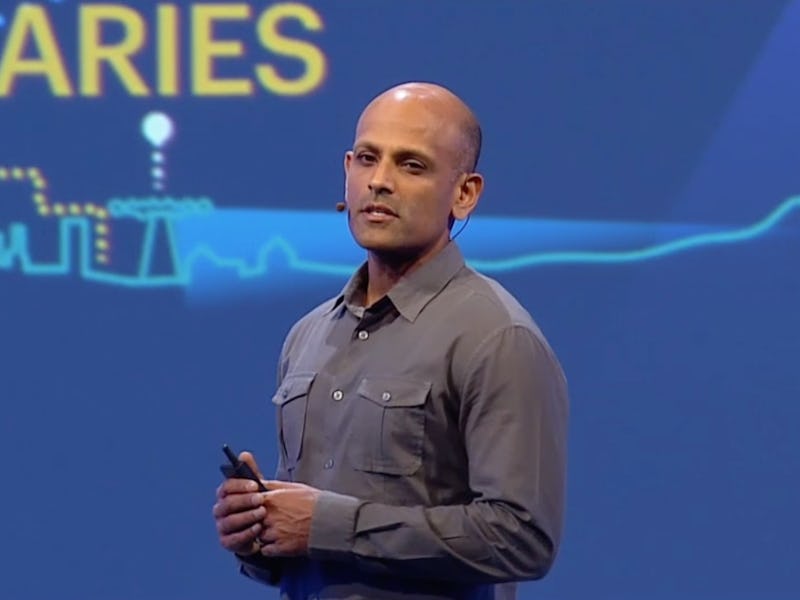

At Facebook’s F8 developer conference keynote today, Jay Parikh announced a bold plan by Facebook to improve the world’s access to internet. Specifically, he unveiled Facebook’s two novel land-based connectivity systems: Terragraph and Project ARIES.

The nitty-gritty: if Terragraph and ARIES advance beyond their current stages, both developed and developing nations will enjoy vast improvements in internet connection access and speeds. Facebook is closing in on kissing 4G networks goodbye and ushering in the future: 5G networks.

The Background

Though it’s not always clear, the internet’s current state is pitiful and outmoded. As far as most of us are concerned, the existing internet is far and away good enough. But we’ve witnessed a drastic change in internet demand and consumption. We’ve seen the supply increase tenfold to keep up with that demand. (Next time you scroll through your Facebook News Feed, see if you can avoid encountering a video. In two years, see if you can avoid encountering a 3D video. In five or ten years, a VR video.) The delivery systems, however — the internet speeds — have long lagged behind. These systems are exceptionally deficient, if not nonexistent, in developing countries, but even in developed countries they’re wanting. Especially once the present catches up with Mark Zuckerberg’s prophesied future of the internet, a ten-year roadmap he laid out during his F8 keynote on Tuesday.

An approximation of connection speeds collected by Facebook.

It’s a future that Facebook may expedite with these projects.

That prophesied future contains — you guessed it — more content. This content, though, is going to be figuratively heavier than ever before. Over the past decade or so, we’ve seen a significant shift in what’s online. Content’s gone from lightweight text to photos; now, videos rule the day. Already video’s proving just as ephemeral; with the advent of virtual- and augmented-reality headsets, an HD video is going to be passé in a matter of moons.

But, for now, videos rule the day: on Facebook, Zuckerberg has explained, the biggest trend is video watching. But even existing networks in developed nations are struggling to support this newborn demand and supply.

Enter Facebook, with its seemingly infinite resources and army of formidable brains. The company that was once just a social network seems to roll out new internet-boon projects biannually, which, for two reasons, makes sense. First, Facebook naturally wants to greatly increase internet speeds, and to do so even in developed countries, so as to entrench itself in our futures. As people begin to share richer and richer social media (4K and 360º video, virtual- and augmented-reality content), social networks will be expected to keep pace. 5G networks, the requirements of which these two initiatives come close to meeting, are rapidly becoming vital. Second, Zuckerberg argues that he and his team have genuine, humanitarian motivations. (“People don’t ever take you for face value on this — we’re really just trying to put people on the internet,” he’s said.)

And so we’ve seen such internet projects as internet-beaming, solar-powered drones, satellites transmitting internet to sub-Saharan Africa, the Telecom Infra projects, and the controversial, much-touted Internet.org program. Most of these projects have focused exclusively on developing nations, where the need is the greatest. (Facebook’s 2015 “State of Connectivity” report gave grim statistical backing to this platitude.)

The project that Parikh, Facebook’s vice president of engineering, announced at F8 will benefit both developing and developed nations.

Terragraph

Terragraph looks to improve the existing systems both at home and abroad. In developing economies, Wireless Product Engineer Neeraj Choubey writes, “mobile networks are often unable to achieve data rates better than 2G.” But even in developed economies, the insufficiencies persist: there, “economies are hampered by WiFi and LTE infrastructure that is unable to keep up with the exponential consumption of photos and video at higher and higher resolutions.”

A prototype Terragraph node.

“Terragraph,” though, “can make an immediate difference to help drive down the cost of providing data while giving people a high quality experience.”

Fiber-optic systems once held enormous promise. But these systems are expensive and difficult to install — especially if you’re in part motivated to connect rural areas. “The high costs associated with laying and trenching the fiber,” Choubey says, make “the goal of ubiquitous gigabit citywide coverage unachievable and unaffordable for almost all countries.” In New York City, LinkNYC is rolling out its own gigabit-network project, but this system uses fiber-optics, which, Facebook says, is neither time- nor cost-efficient.

Terragraph is one of Facebook’s two connectivity solutions, and it’s meant to bring “high-speed internet connectivity to dense urban areas.” Facebook believes that, “combined with WiFi access points,” Terragraph will be “one of the lowest-cost solutions to achieve 100 percent street level coverage of gigabit WiFi.” And: “…we think this number can be much higher in the future.”

Terragraph’s technicalities get fairly, shall we say, technical, but, in broad strokes, here’s how it works. “Terragraph is a 60-GHz, multi-node wireless system” that uses “commercial off-the-shelf components and [leverages] the cloud for intensive data processing.” As it’s “optimized for high-volume, low-cost production,” it’s ideal for these dense urban areas.

If your home wifi connection is like mine, it’s got both 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz networks. The former offers better range but slower internet; the latter offers faster internet but limits range. Now imagine one that goes to 60.

Each number's color corresponds to a color on the map.

To compensate, these nodes will be interspersed throughout cities at about 650- to 800-foot intervals. “Given the architecture of the network,” Facebook writes, “Terragraph is able to route and steer around interference typically found in dense urban environments, such as tall buildings or internet congestion due to high user traffic.” Each node quickly and efficiently bounces the signal around the neighborhood, and voila: wicked fast internet for all.

Facebook is currently testing Terragraph at its headquarters in Menlo Park, California, and plans to roll out a “broader trial” in San Jose. It also hopes to one day implement the advancements into the Telecom Infra Project.

“We’ll continue to invest in the program with our partners by building large-scale trial networks in multiple markets around the world to demonstrate the potential value and efficiency of the technology. We are working on making this technology open and interoperable via unlicensed spectrum, just like WiFi itself.”

Project ARIES

Antenna Radio Integration for Efficiency in Spectrum

Project ARIES is another initiative that Facebook hopes will improve internet access. In essence, it’s a serious push to bring cellular networks up from 4G to 5G. Technically speaking: Instead of the by-now-traditional but energy-consumptive multiple input-multiple output (MIMO) 4G systems, ARIES uses “an embodiment of” massive MIMO technology. In plain English, that means the system employs many antennas that support more users with fewer issues.

Here’s what Parikh said today: “We thought to ourselves: how do we make this awesome ? Well, obviously, we just add more antennas.”

The ARIES prototype.

This technology, along with the team’s soon-to-be “unprecedented” work on spectrally efficient and energy efficient transmitters, may revolutionize both the speed of and distance at which you can access the internet.

“ARIES is our proof-of-concept effort to build a test platform for incredibly efficient usage of spectrum and energy; a base station with 96 antennas, it can support 24 user devices simultaneously over the same radio spectrum. We currently are able to demonstrate 71 bps/Hz of spectral efficiency and when complete, ARIES will demonstrate an unprecedented 100+ bps/Hz of spectral efficiency.”

For reference, existing LTE networks max out at 30 bps/Hz.

Facebook hopes to use ARIES to provide high-speed connectivity to “rural communities from city centers” while keeping infrastructural costs low. Previous Facebook research generated extremely precise population maps that lend credence to ARIES’s practicality: since Facebook now knows that “nearly 97 percent of people live within [25 miles] of a major city,” it just needs to develop relatively low-cost, non-invasive, more efficient cellular networks that will access those people. (If Facebook does develop the technology, it’ll share it with academic and research communities to expand use of the system.)

If it manages to pull that off, Facebook will have achieved what it set out to do: connect (virtually) the whole world; enable all to share whatever, whenever, to whomever.