Weirdly Long-Lived Radio Signal Hints at Undiscovered Astrophysics

Spoiler alert: it's not aliens. We want to believe, too, but it's not aliens.

Somewhere out in space, a dead star is doing weird stuff, and we don’t know why – yet.

International Center for Radio Astronomy Research astronomer Natasha Hurley-Walker and her colleagues recently detected a radio signal that has repeated every 21 minutes for more than 30 years. No, it’s probably not aliens. But it’s almost certainly some really cool astrophysics that we just don’t understand yet.

They published their findings in the journal Nature.

A Signal from Space

Around 18,000 light years away along the galactic plane, something is blasting pulses of radio waves toward Earth once every 21 minutes. Each radio pulse lasted between 3 seconds and 5 minutes. Hurley-Walker and her colleagues first noticed the pulses when they pointed the Murchison Widefield Array, a radio telescope in Australia, along the Milky Way’s equator, or galactic plane. When they checked archived data from several other radio telescopes, they found that the signal, dubbed GPM J1839–10, had been repeating since at least 1988.

The mysterious object is probably not aliens, although some of the data Hurley-Walker and her colleagues used actually came from SETI projects like Breakthrough Listen.

But lots of things in space send regular radio signals toward Earth, and most of them are the remains of dead stars. (Space is often spooky.) This newly-discovered signal has some traits in common with a few of those objects, but some of its other characteristics don’t quite match any of them. That leaves astrophysicists with a puzzle to solve over the next few years.

Not a Pulsar (As We Know It)

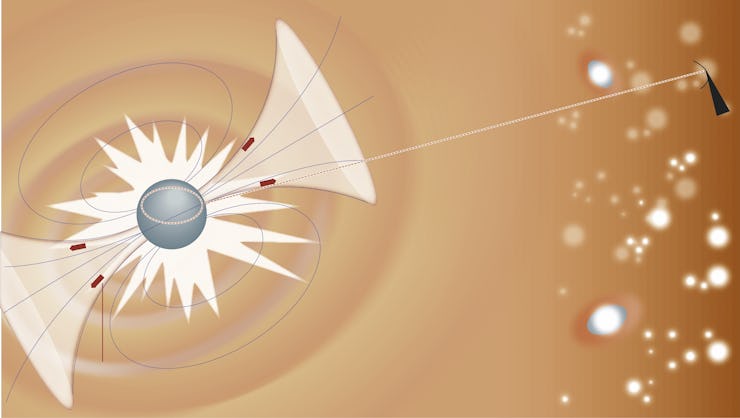

It looks a little like a typical pulsar: a fast-spinning, incredibly dense ball of neutrons left behind when a massive star explodes, which blasts streams of high-speed electrons and radio beams out into space like a lighthouse as it rotates. The radio waves in Hurley-Walker and her colleagues’ signal are polarized — and their polarization changes during the pulse — almost exactly the way you’d expect from a pulsar. That means the physics at work are probably pretty similar. But because GPM J1839–10’s signal repeats so slowly, there’s probably something very different happening, too.

If a neutron star doesn’t spin fast enough, its magnetic field can’t generate the electrical current needed to produce radio beams and become a pulsar. By “fast enough,” we mean once every few seconds, or even every few milliseconds. A neutron star rotating once every 21 minutes just wouldn’t generate enough current to produce radio signals we could see from Earth.

An artist’s depiction of a pulsar

So What Could It Be?

The only object astronomers have ever caught sending out a slowly-repeating radio signal even remotely similar to GPM J1839–10 was something called GLEAM-XJ162759-5-523504.3, which pulsed out radio waves every 18 minutes — but only for about three months. Hurley-Walker and her colleagues suggest that one may have been in the throes of a reshuffling of its magnetic field, which caused it to blast out radio waves like a magnetar for a while until things settled down.

But GPM J1839–10 has been going for more than 30 years now, much too long for a quick magnetic field shift. Something else is happening.

One possible culprit is a different type of dead star called a white dwarf, which is the burned-out core of a star about the size of our Sun. White dwarfs are larger and spin much more slowly than neutron stars, so one rotation every 21 minutes would make perfect sense for a white dwarf. In theory, a white dwarf with a powerful enough magnetic field could produce radio beams, like a very slow pulsar.

On the other hand, only one white dwarf out of thousands, a dead star known as ARSco, has ever produced this kind of radio signal — and that was 1,000 times less bright than GPM J1839–10. So while it’s possible, it doesn’t look terribly likely, unless there’s a whole class of slowly-pulsing white dwarfs that astronomers until now didn’t know about. Which is actually possible.

What We Know

GPM J1839–10 is probably some kind of remnant of a massive star, and it’s probably slowly sending out a beam of radio waves as it rotates. For now, however, exactly which type of stellar core remnant it is, or why it behaves the way it does, remains a mystery. And it’s not the only one.

In their recent paper, Hurley-Walker and her colleagues point out that several other strange cosmic radio signals – including some that repeat at regular intervals, like GPM J1839–10 – are still stirring up debates among atstrophysicists who aren’t sure exactly what’s producing the signals (we’re sorry, but it’s still probably not aliens). The answers may lie in archived radio data and in future observations.

“Only time will tell what else lurks in these data, and what observations across many astronomical timescales will reveal,” writes McGill University astrophysicist Victoria Kaspi, in a recent paper commenting on the study.