When Will Betelgeuse Explode? A Controversial New Study Says "Soon"

But most astronomers aren’t so sure.

We’ve all resigned ourselves to not seeing Betelgeuse explode, but at least one team of astronomers is still holding out hope.

If we’re ever going to see a nearby supernova, then Betelgeuse, the bright red supergiant on the right shoulder of the constellation Orion, is our best chance. But despite taunting us through early 2020, and again with recent brightening, the star stubbornly refuses to explode. Most recent studies agree that a Betelgeuse supernova won’t happen in our lifetimes, but one team of astronomers suggests it could actually happen in the next few decades.

It all depends on how big Betelgeuse actually is.

Where’s the Earth-Shattering Kaboom?

Ask an astrophysicist, and they’ll probably tell you that right now, in the center of Betelgeuse, tremendous heat and pressure are fusing helium atoms together into carbon atoms. If that’s the case, the supergiant star has several more stages — and several thousand years — to go through before finally, it fuses its last silicon atom into iron, burns itself out, and collapses under its own gargantuan weight, triggering an explosion so powerful it will be visible from other galaxies.

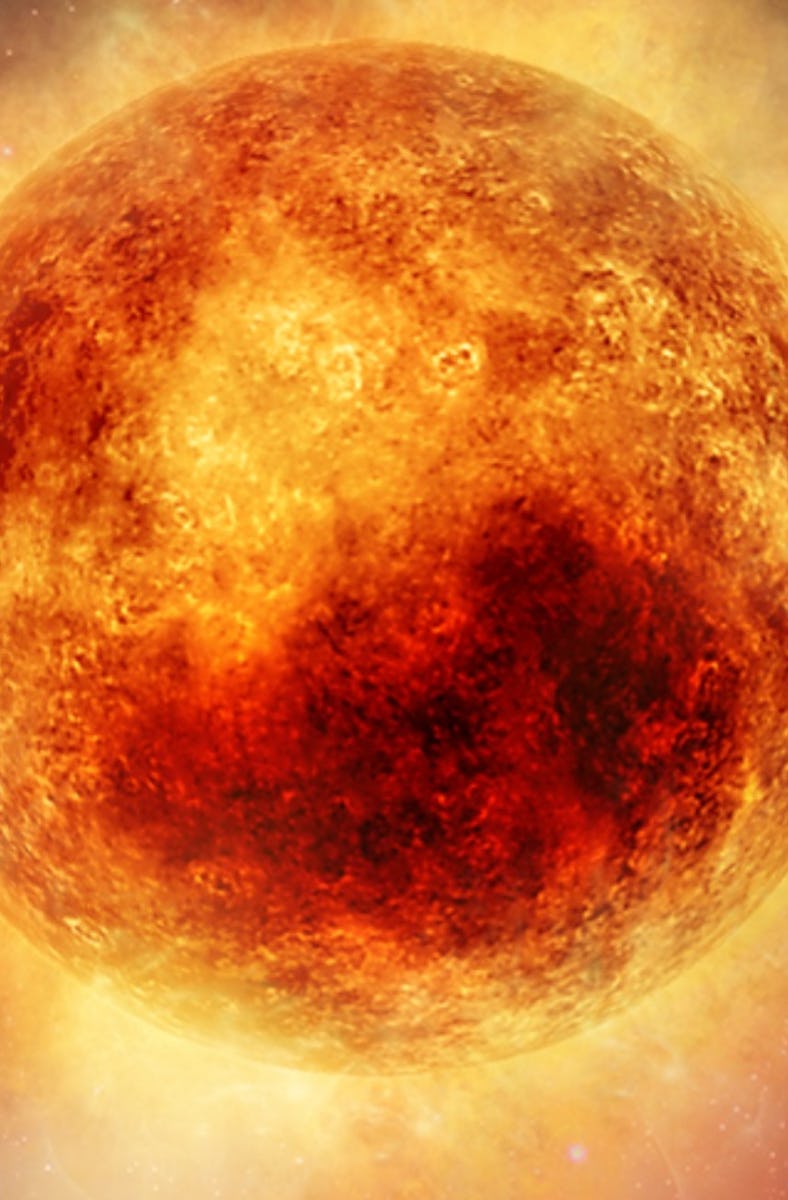

This NASA illustration of Betelgeuse shows the star shortly after the infamous Great Dimming of late 2019 and early 2020.

But in a recent preprint (not yet peer-reviewed and published) study, Tohoku University astronomer Hideyuki Saio and his colleagues suggest that instead, the star is already almost finished burning carbon — and after that, it’ll only take a few decades to run through oxygen and silicon. Saio and his colleagues base their claim on how often the star pulses, or brightens and dims.

Betelgeuse has a history of pulsing on regular cycles, like a beating heart on a cosmic scale. The cycle astrophysicists consider the most important takes 420 days to dim and brighten again. During those 420 days, the whole interior of the star expands and contracts at the same time (that’s called radial pulsation). Two other, shorter cycles of brightening and dimming are what’s called overtone modes; different layers of the star pulse on opposite cycles but at the same time, so one layer contracts while the next layer expands.

“These pulsations are self-excited in the envelope of Betelgeuse due to the instability in the energy flow there,” Saio tells Inverse.

Astronomers have also noticed a much longer cycle of brightening and dimming coming from Betelgeuse, one that takes about 2,200 days — more of a “slow undulation,” as astronomer Laszlo Molnar, of Kokoly Observatory in Hungary, and his colleagues, describe it. Most astronomers have assumed this longest cycle wasn’t part of what’s called radial pulsation, but instead caused by something outside the star, like nearby dust. That’s a pretty common phenomenon in red giants and supergiants like Betelgeuse.

Saio and his colleagues, on the other hand, say the 2,200-day cycle is actually Betelgeuse’s main period of radial pulsation, when the whole star expands and contracts at once.

Thanks to the physics of how stars work, if Betelgeuse pulses on that long a cycle, it must have a larger radius than most astronomers believe it does: about 1,300 or 1,400 times that of our Sun, compared with previous estimates of 600 or 1,000 times the radius of our Sun.

Based on computer models, says, Saio, “We have found that the evolutionary stage of the model with such a large radius should be in a late stage of the carbon burning.” If Saio and his colleagues are correct, Betelgeuse could explode in the next several decades.

Actually, Size Does Matter

But according to other astronomers, that’s a big “if.”

“They assume a much larger radius than is observed,” Harvard University astrophysicist Andrea Dupree tells Inverse.

Molnar and his colleagues make the same point in their recent counterargument to Saio and his colleagues, which they published in the Research Notes of the American Astronomical Society. Telescopes have observed Betelgeuse in several wavelengths of light, and according to Molnar and his colleagues, all of that data rules out Betelgeuse being any bigger than 1,100 times the size of our Sun — not big enough for the whole star to pulse on that huge, slow 2,200-day cycle.

In other words, the data telescopes around the world (and in orbit) have gathered over the years just doesn’t point to Betelgeuse being big enough or old enough to explode anytime soon.

“The star WILL go supernova,” Dupree tells Inverse, “but not in our lifetimes.”

Maybe if we say its name three times, that might speed things up. What’s the worst that could happen?