Over 100 Years Later, Astronomers Finally Have a Clear View of Einstein's Wildest Theory

LIGO is finally back — and it’s better than ever.

After a three-year hiatus, scientists in the U.S. have just turned on detectors capable of measuring gravitational waves — tiny ripples in space itself that travel through the universe.

Unlike light waves, gravitational waves are nearly unimpeded by the galaxies, stars, gas, and dust that fill the universe. This means that by measuring gravitational waves, astrophysicists like me can peek directly into the heart of some of these most spectacular phenomena in the universe.

Since 2020, the Laser Interferometric Gravitational-Wave Observatory — commonly known as LIGO — has been sitting dormant while it underwent some exciting upgrades. These improvements will significantly boost the sensitivity of LIGO and should allow the facility to observe more-distant objects that produce smaller ripples in spacetime.

By detecting more events that create gravitational waves, there will be more opportunities for astronomers to also observe the light produced by those same events. Seeing an event through multiple channels of information, an approach called multi-messenger astronomy provides astronomers rare and coveted opportunities to learn about physics far beyond the realm of any laboratory testing.

Ripples in spacetime

According to Einstein’s theory of general relativity, mass and energy warp the shape of space and time. The bending of spacetime determines how objects move in relation to one another — what people experience as gravity.

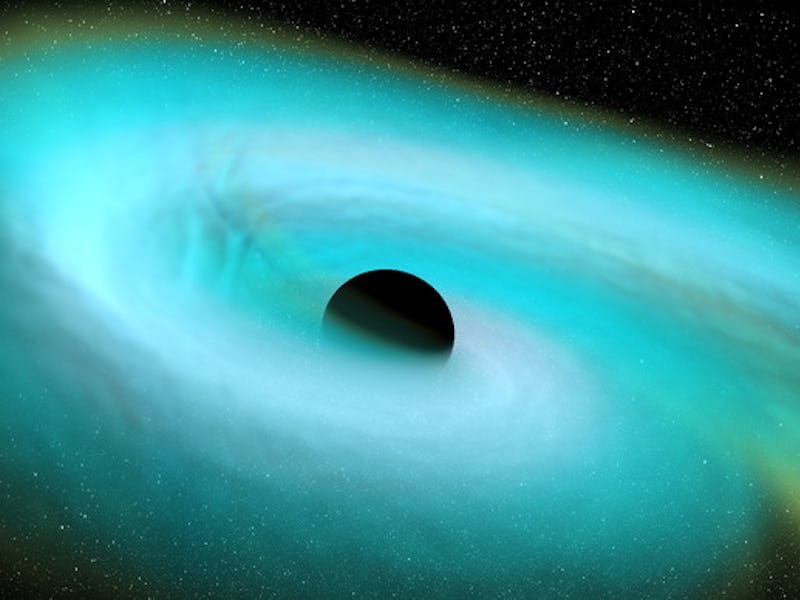

Gravitational waves are created when massive objects like black holes or neutron stars merge with one another, producing sudden, large changes in space. The process of space warping and flexing sends ripples across the universe like a wave across a still pond. These waves travel out in all directions from a disturbance, minutely bending space as they do so and ever so slightly changing the distance between objects in their way.

Even though the astronomical events that produce gravitational waves involve some of the most massive objects in the universe, the stretching and contracting of space is infinitesimally small. A strong gravitational wave passing through the Milky Way may only change the diameter of the entire galaxy by three feet (one meter).

The first gravitational wave observations

Though first predicted by Einstein in 1916, scientists of that era had little hope of measuring the tiny changes in distance postulated by the theory of gravitational waves.

Around the year 2000, scientists at Caltech, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and other universities around the world finished constructing what is essentially the most precise ruler ever built — the LIGO observatory.

The LIGO detector in Hanford, Wash., uses lasers to measure the minuscule stretching of space caused by a gravitational wave.

LIGO is comprised of two separate observatories, with one located in Hanford, Washington, and the other in Livingston, Louisiana. Each observatory is shaped like a giant L with two 2.5-mile-long (four-kilometer-long) arms extending out from the center of the facility at 90 degrees to each other.

To measure gravitational waves, researchers shine a laser from the center of the facility to the base of the L. There, the laser is split so that a beam travels down each arm, reflects off a mirror, and returns to the base. If a gravitational wave passes through the arms while the laser is shining, the two beams will return to the center at ever so slightly different times. By measuring this difference, physicists can discern that a gravitational wave passed through the facility.

LIGO began operating in the early 2000s, but it was not sensitive enough to detect gravitational waves. So, in 2010, the LIGO team temporarily shut down the facility to perform upgrades to boost sensitivity. The upgraded version of LIGO started collecting data in 2015 and almost immediately detected gravitational waves produced from the merger of two black holes.

Since 2015, LIGO has completed three observation runs. The first, run O1, lasted about four months; the second, O2, about nine months; and the third, O3, ran for 11 months before the COVID-19 pandemic forced the facilities to close. Starting with run O2, LIGO has been jointly observing with an Italian observatory called Virgo.

Between each run, scientists improved the physical components of the detectors and data analysis methods. By the end of run O3 in March 2020, researchers in the LIGO and Virgo collaboration had detected about 90 gravitational waves from the merging of black holes and neutron stars.

The observatories have still not yet achieved their maximum design sensitivity. So, in 2020, both observatories shut down for upgrades yet again.

Making some upgrades

Scientists have been working on many technological improvements.

One particularly promising upgrade involved adding a 1,000-foot (300-meter) optical cavity to improve a technique called squeezing. Squeezing allows scientists to reduce detector noise using the quantum properties of light. With this upgrade, the LIGO team should be able to detect much weaker gravitational waves than before.

My teammates and I are data scientists in the LIGO collaboration, and we have been working on a number of different upgrades to software used to process LIGO data and the algorithms that recognize signs of gravitational waves in that data. These algorithms function by searching for patterns that match theoretical models of millions of possible black hole and neutron star merger events.

The improved algorithm should be able to more easily pick out the faint signs of gravitational waves from background noise in the data than the previous versions of the algorithms.

Astronomers have captured both the gravitational waves and light produced by a single event, the merger of two neutron stars. The change in light can be seen over the course of a few days in the top right inset.

A hi-def era of astronomy

In early May 2023, LIGO began a short test run — called an engineering run — to make sure everything was working. On May 18, LIGO detected gravitational waves likely produced by a neutron star merging into a black hole.

LIGO’s 20-month observation run 04 will officially start on May 24, and it will later be joined by Virgo and a new Japanese observatory – the Kamioka Gravitational Wave Detector, or KAGRA.

While there are many scientific goals for this run, there is a particular focus on detecting and localizing gravitational waves in real time. If the team can identify a gravitational wave event, figure out where the waves came from, and alert other astronomers to these discoveries quickly, it would enable astronomers to point other telescopes that collect visible light, radio waves, or other types of data at the source of the gravitational wave.

Collecting multiple channels of information on a single event — multi-messenger astrophysics — is like adding color and sound to a black-and-white silent film and can provide a much deeper understanding of astrophysical phenomena.

Astronomers have only observed a single event in both gravitational waves and visible light to date — the merger of two neutron stars seen in 2017. But from this single event, physicists were able to study the expansion of the universe and confirm the origin of some of the universe’s most energetic events known as gamma-ray bursts.

With run O4, astronomers will have access to the most sensitive gravitational wave observatories in history and hopefully will collect more data than ever before. My colleagues and I are hopeful that the coming months will result in one – or perhaps many – multi-messenger observations that will push the boundaries of modern astrophysics.

This article was originally published on The Conversation by Chad Hanna at Penn State. Read the original article here.