Counterintuitive study reveals 1 strange result of human evolution

Prominent noses may explain a critical difference between humans and other apes.

From the persistent calls to drink more water, it would seem like people are constantly dehydrated. But according to a new study, the human body is extraordinarily good at conserving water — at least, compared to other members of the primate family.

Humans, it turns out, are the water-saving ape.

This finding was published Friday in the journal Current Biology. The research was led by scientists at Duke University.

Here's the background — It's no secret that humans sweat. A lot. According to the study, humans sweat in excess of two liters per hour when experiencing heat stress, such as in warmer environments.

That's significantly more sweating than our great ape kin. Humans sweat at a rate 4 to 10 times greater than chimpanzees, the study reports.

While people need to drink water on a daily basis, great apes in the rainforest can go several days or weeks without drinking water. They meet most of their water needs through their food.

But surprisingly, this study reveals humans actually conserve water more efficiently than other apes.

Herman Pontzer is the study's lead author and an associate professor of evolutionary anthropology at Duke University. "We use much less water than other apes," Pontzer tells Inverse.

How they did it — Using a technology known as isotope depletion, which involves enriching large biomolecules, the researchers compared water turnover between humans and other apes.

A Western lowland gorilla takes a sip.

Specifically, the scientists compared apes in zoos and rainforest sanctuaries to five different human populations, including modern hunter-gatherer populations. The other apes studied include chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, and orangutans.

The researchers stated that water turnover correlates strongly with four factors:

- Energy expenditure

- Physical activity

- Climate (temperature and humidity)

- Fat-free mass

These correlating variables ultimately help us understand how lower water turnover in humans leads to greater water conservation.

What's new — After conducting their analysis, the researchers came away with three key findings:

- Humans evolved to use fewer liters of water per day than other apes

- Humans have a lower water drinking/energy ratio than other apes

- The nature of water conservation in humans is still unclear, but noses might play a role

Despite sweating significantly, humans conserved more water, according to the study.

Digging into the details — Specifically, scientists learned that water turnover was 30 to 50 percent lower in humans compared to other apes.

Among the humans, modern hunter-gatherers had the highest water turnover rates. Manual laborers experienced higher rates than sedentary workers, but still lower than hunter-gatherers. Humans in hotter environments experienced greater water turnover, likely due to sweat.

However, even taking into account differing water turnover rates among humans, the five different human groups studied still had a lower overall water-to-energy consumption ratio compared to other apes.

According to the study:

"These changes are evident among living populations today: compared to the diets of forest-living wild apes, modern hunter-gatherer diets have [approximately] 80 percent more energy per gram of dry matter and hold [approximately] 80 percent less water per kcal; diets of industrialized human populations are equally dry."

Among apes, chimpanzees and bonobos experienced the greatest water turnover, and gorillas the lowest. Notably, apes in rainforest sanctuaries could meet their water needs through diet, but apes in U.S zoos drank an average of 2 to 5 liters of water per day due to their drier diets.

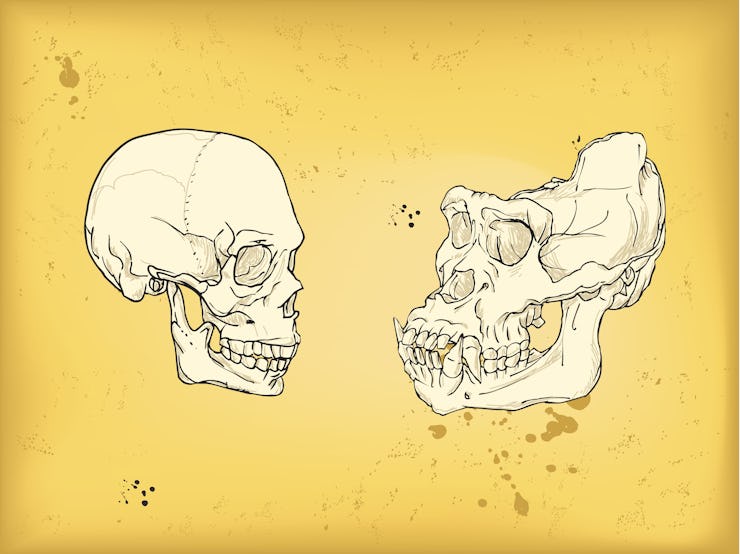

The researchers suggest that the prominent noses of humans — compared to other apes' flatter nasal passages — might account for the difference in water conservation.

According to Pontzer, humans are the only apes to possess an external nose. Our nose began evolving about 2.5 million years ago, possibly around the time that Homo habilis — the "handy man" that could use stone tools — evolved.

"We know from studies in living humans that our noses help trap the moisture in the air we exhale, which reduces water loss from exhaled air," Pontzer says.

"The hypothesis is that the external nose evolved as an adaptation to reduce water loss."

A chimpanzee named "Can" enjoys the outdoor with its caretaker at Gaziantep zoo in Turkey. The study has implications for apes living in zoos.

Why it matters — The researchers speculate there may be one simple reason that humans evolved to better conserve water: our past foraging habits.

While other apes largely remained in one habitat and didn't stray too far from home, humans gradually began to do the opposite.

As they traveled long distances to hunt and begin eating meat, humans had to evolve in order to conserve water more efficiently. This enabled survival, especially in hotter climates.

The researchers write in the study that these developments may have occurred during the Pleistocene era, which began some 2.5 million years ago:

"Adaptations to reduce water demands may have been essential in enabling early Homo to venture farther from open water sources and pursue a physically demanding foraging strategy."

Despite recent research suggesting humans and apes are pretty similar, the ability to conserve water is one major difference.

What's next — If humans are better at conserving water than apes, does that mean we should change up our water drinking habits? Not really, according to Pontzer.

"No — we already had a good idea of human water needs," Pontzer says.

"What we didn’t know, and what this study adds, is how our water needs compare to our ape cousins."

The study, in turn, has greater immediate implications for other members of the great apes family. The unbalanced ratio of water to dry food in zoo diets may be causing digestive problems for apes, according to the researchers.

"The important health application here is really for apes. It appears from our work that they are adapted to eat a rather wet diet — a high ratio of water to calories," Pontzer says.

The researchers believe their findings will help zoos tailor diets to better fit apes' water consumption needs.

"However, zoo diets are often drier than would be optimal for them, and with less fiber. Our results might be useful for improving diets for apes in zoos and sanctuaries," Pontzer says.

Summary: To sustain life, humans and other terrestrial animals must maintain a tight balance of water gain and water loss each day.1–3 However, the evolution of human water balance physiology is poorly understood due to the absence of comparative measures from other hominoids. While humans drink daily to maintain water balance, rainforest-living great apes typically obtain adequate water from their food and can go days or weeks without drinking4–6. Here, we compare isotope-depletion measures of water turnover (L/d) in zoo- and rainforest-sanctuary-housed apes (chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, and orangutans) with 5 diverse human populations, including a hunter-gatherer community in a semi-arid savannah. Across the entire sample, water turnover was strongly related to total energy expenditure (TEE, kcal/d), physical activity, climate (ambient temperature and humidity), and fat free mass. In analyses controlling for those factors, water turnover was 30% to 50% lower in humans than in other apes despite humans’ greater sweating capacity. Water turnover in zoo and sanctuary apes was similar to estimated turnover in wild populations, as was the ratio of water intake to dietary energy intake (~2.8 mL/kcal). However, zoo and sanctuary apes ingested a greater ratio of water to dry matter of food, which might contribute to digestive problems in captivity. Compared to apes, humans appear to target a lower ratio of water/energy intake (~1.5 mL/kcal). Water stress due to changes in climate, diet, and behavior apparently led to previously unknown water conservation adaptations in hominin physiology.

This article was originally published on