60 years ago, a space chimpanzee made history — and left a dark legacy

Enos the chimpanzee orbited the Earth before John Glenn. Neither Enos or John were happy about that.

In terms of the human family, as most broadly defined, the first three to orbit around Earth were Soviet cosmonauts Yuri Gagarin and Gherman Titov and American astronaut Enos.

That is, Enos the Chimpanzee, who was launched into orbit in a Mercury capsule on November 29, 1961, much to the chagrin of the human Mercury astronauts.

“Enos is interesting because he’s actually the third hominid in orbit,” University of Chicago space historian and National Air and Space Museum Guggenheim fellow Jordan Bimm tells Inverse. “That’s not the kind of record the human astronauts really wanted to see. They would have much preferred that be Colonel John Glenn.”

Enos would probably have preferred John Glenn take his seat too, as Bimm notes some fairly horrific spacecraft malfunctions resulted in a harrowing flight for the chimpanzee, who afterward was mostly ignored by the press. By contrast, Ham the chimpanzee, whose January 31, 1961, suborbital flight paved the way for Alan Shephard’s subsequent suborbital mission aboard Freedom 7, would grace the cover of LIFE Magazine.

And that sort of celebration is part of the ethically dubious legacy of early animal spaceflight, according to Bimm. Enos’s story is an important part of space history because he made John Glenn’s orbital flight of February 20, 1962, possible, but it’s also a dark tale worth interrogating with clear eyes and without assumptions.

When it comes to space chimps, “We shouldn’t try and anthropomorphize them in ways that make them seem like little astronauts,” Bimm says. “That implies that they have some sort of agency.”

Space monkeys, space race— To understand the story of Enos, you need to appreciate that he was a part of two human environments beyond his ken: The space race and the closely associated Cold War between the US and USSR.

The perception in America in the late 50s and early 60s, Bimm notes, was that the Soviets had a significant lead in space and the United States needed to catch up. The Soviets launched the first artificial satellite, Sputnik, in 1957, and the first human in space, Yuri Gargarin, in April 1961, the latter being an orbital flight while NASA was still aiming for its first suborbital mission.

In that environment, NASA launched Ham as a test run for Alan Shepard’s May 1961 suborbital flight, and his preceding the first American man into space was part of his celebrity. But after Shepard’s flight, both the Mercury astronauts and the public wanted an American man in orbit, not another simian.

“You can imagine their frustration, given their sort of outsized egos, when they had to sit on the sidelines while an animal sat in their seat,” Bimm says.

But the space race was never just about beating the Soviets to arbitrary milestones in space.

Space medicine as a specific discipline started in the US before NASA even existed, with an institute formed within the Air Force in 1949. The Army and Air Force were launching smaller animals to the edge of space for more than a decade before Ham and Enos as part of a general Cold War obsession with human performance in extreme conditions, Bimm says. And not just any performance, but military performance — Enos had another role to play beyond being a living biosensor.

“With Enos, the question was, ‘Can that simulated human perform meaningful work in rocket flight and in the orbital space environment?’” he says. “The question there was, can a soldier perform a military task during spaceflight?”

Purchased by the Air Force from a Miami rare birds farm in April 1960, Enos would receive more than 1,200 hours of training prior to his orbital mission, most of it centered on training the chimpanzee to operate a simulated work apparatus to mimic controls a human pilot might operate during a military rocket flight. Enos came ahead of four other chimps, winning him the privilege of flying the orbital mission ahead of John Glenn.

“They put the chimpanzees in the simulators and they ran them for 270 minutes,” Bimm says, about the length of three orbits, “which is what they were thinking the flight would be at the time.”

Once the humans had their chimp, there was just one more thing to do: name him.

“The names of these experimental animals are very superficial and usually only given to the animals right before the moment of launch,” Bimm says. “It’s important to know that before Ham was called Ham, he was called number 65. And before Enos was called Enos, he was called number 81.”

The names themselves are Biblical. It could be that some of the humans involved really had a conception of space medicine ushering in some new age of human evolution — Enos means “mortal man” in ancient Hebrew, Bimm notes.

“There were other folks who were just like, ‘Yeah, whatever works for the media,’” he says. “Whatever distracts from the fact that we’re literally torturing these animals to the edge of death.”

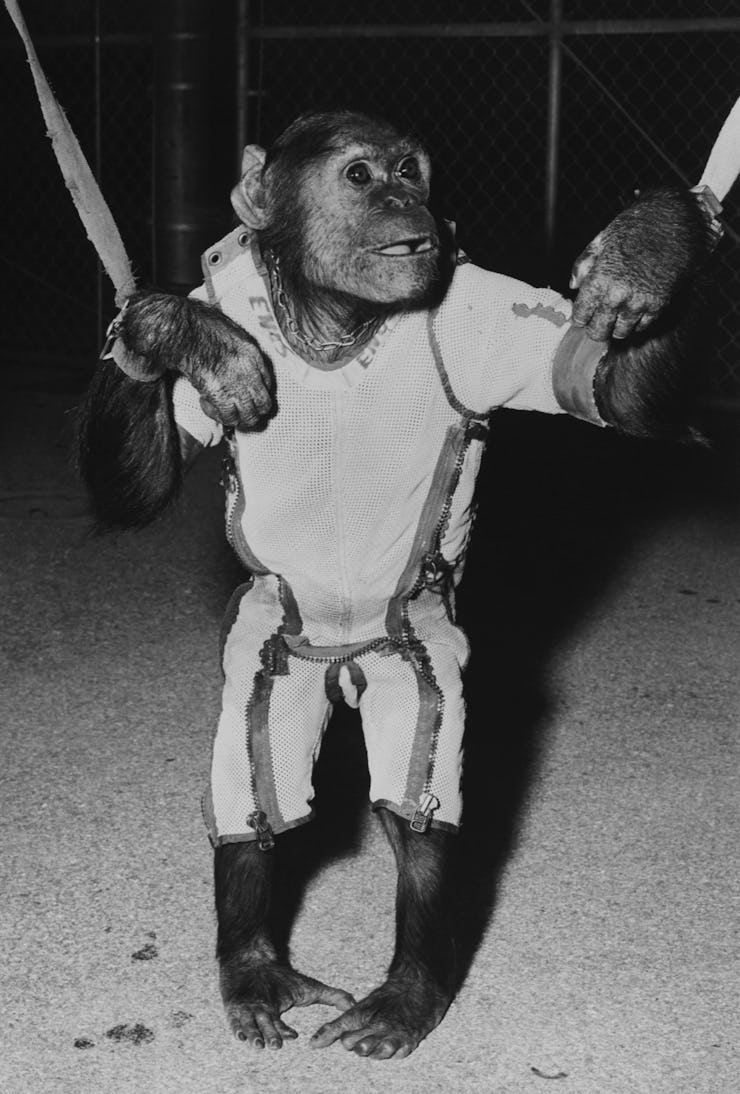

Enos just before his flight.

What happened to Enos during his space flight?

The newly named Enos blasted off on November 29, and whether or not he ushered in a new age for mankind, things certainly went badly for him.

A thruster malfunctioned right out of the gate, causing the Mercury space capsule to lose attitude control. “Also, the environmental control system stops working,” Bimm says. The spacecraft interior began to grow hotter and hotter, and “Enos would have felt that.”

He also would have felt confusing, frustrating, and inescapable electric shocks to his feet. NASA synced Enos’ training to pleasurable and painful feedback systems. In one task, he would pull a lever so many times in a row when cued in order to get water or some food. But in another, where he had to pull a lever correctly identifying a shape when displayed on a screen, Enos would receive an electric shock if he chose wrong.

“The shock avoidance mechanism malfunctioned in a horrific way,” Bimm says. “Not only did it not function, it actually reversed its functionality.”

Every correct answer Enos gave now resulted in a painful electric shock. A chimpanzee who never chose to be there was now locked in a cramped and overheating spacecraft, doing everything right but repeatedly receiving punishment anyway — Enos was shocked 76 times for giving the correct answer, according to Bimm.

“It just seems like something out of a mad scientist horror story or something,” he adds.

Enos getting a post-flight check-up.

Semisweet relief— Thankfully, Enos’s flight was cut short, though not due to concerns over his suffering. “Due to the stuck thruster, they decided to actually conclude the flight after the second orbit instead of going for three orbits,” Bimm says.

Enos’s Mercury spacecraft safely re-entered the atmosphere and splashed down in the Atlantic Ocean near Bermuda, where the recovery team encountered a horrific scene.

Researchers inserted multiple catheters into Enos, including three in his heart and one in his bladder. In a scene perhaps eerily premonitory and similar to the episode during the ill-fated Apollo 13 mission where astronauts Jim Lovell, John Swigert, and Fred Haise removed their vitals monitoring electrodes, Enos had ripped almost all the catheters out —yes, including that one — leaving just one in his heart.

“They said it was a real mess in there,” Bimm says. An attending Air Force doctor said that if Enos had pulled the last cardiac catheter out, he would have bled to death.

There was, at least, an end to the hot, painful ordeal for Enos, and a sweet reward.

“I believe immediately afterward, he was fed an orange cut into fours and an apple cut into fours,” Bimm says. “He enjoys that.”

A tale of two chimps— Sadly, those fruit slices might have been the peak for Enos, as the rest of his story is a bit of a downer. He died within a year of the flight.

“He died in early November 1962 of dysentery,” Bimm says. “They claimed it was not related to his spaceflight, just something that he caught when he went back to the chimpanzee colony at Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico.”

Ham, the fortunate one, lived until 1983, and at least some of his remains were later buried at the New Mexico Museum of Space History. There was no such honor for Enos, Bimm says, “and it’s really sketchy as to what even happened to his body.”

It’s a post-mortem legacy that tracks the coverage of the two animals when they were alive. While Ham was a cuddly space monkey, Enos was considered cold, rude, and really just kind of a dick.

“The big headline is like, unlike Ham, who was cute and cuddly, Enos was, like, mean, mean spirited, or uncooperative,” Bimm says. “He eventually gets this nickname, ‘Enos the Penis.’”

John Glenn shortly after his history-making flight.

A dark legacy— The way Bimm sees it, both the celebration of Ham and calling Enos a penis are problematic cases of misplaced anthropomorphization. “Enos was an experimental animal who was treated just absolutely horribly,” Bimm says. “And so I think we should understand his behavior in the context of that rather than trying to, you know, pigeonhole him into a sort of a human actor’s category.”

It would later turn out that some of the medical data from Enos’s flight was useless because researchers realized they weren’t measuring the chimpanzee’s physiological response to the stressors of space flight as much as to the stressors they had placed on him. Enos exhibited signs of heart arrhythmias during his flight, Bimm says, that were ultimately caused by all of the catheters and electric shocks, not microgravity.

And yet, Enos’s flight did not spell the end of non-human primate astronauts. Squirrel monkeys flew on an early shuttle mission, Bimm says, and Iran launched a monkey on a suborbital spaceflight as recently as 2013.

“The idea is not 100 percent dead,” he says.

What can we say about Enos today? It’s certainly true that without his flight, John Glenn’s orbital flight may have been delayed, and in that sense, Enos played a vital role in the human space program.

But it’s important to recognize that Enos had no choice in the matter. And either ignoring the dark parts of his and similar animal experiments, or celebrating them as if they were humans, both demean human astronauts while letting us — humans — off the hook for how we have used our cousins in the past.

“It’s important to remember these dark moments,” Bimm says. “Space history should not be just about celebrating the triumphs. It should be deeply introspecting and thinking through some of these other moments that are way more complicated. What can we learn here?”