The collision of cosmic beasts sings a loud gravitational wave hum

The sound produced was similar to the overtones of musical instruments.

We already know the universe to be quite the artist, creating visual masterpieces from the swirling movements of clouds of dust, hot gas and stellar explosions. And now, one rare cosmic occurrence in the vast universe can be heard as well.

A team of researchers have detected, or rather heard, a gravitational wave that is much louder than usual, produced by the merger of two black holes that they dubbed GW190412.

“For the very first time we have ‘heard’ in GW190412 the unmistakable gravitational-wave hum of a higher harmonic, similar to overtones of musical instruments,” Frank Ohme, leader of the Independent Max Planck Research Group, and co-author of the study, said in a statement.

GW190412 was observed by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) detectors and the Virgo detector on April 12, 2019, taking place 1.9 to 2.9 billion lightyears away from Earth. The observation is detailed in a study published this week on arXiv.

A binary black hole system consists of two black holes orbiting close around one another, drawing closer and closer until they merge into a single black hole. When two cosmic objects of this size orbit each other, they shake up the fabric of spacetime, creating ripples at the speed of light, which results in gravitational waves.

The reason why the sound was so unique is because the mass of the two black holes was vastly different. One of the black holes was eight times the mass of the Sun, while its opponent had an unfair advantage with a mass 30 times the mass of the Sun. Therefore, the gravitational wave frequency from each of the black holes' orbit was different.

The larger black hole was likely producing a lower frequency, while its smaller companion was producing a higher frequency. Combining those two frequencies together resulted in that musical hum recently detected by the researchers.

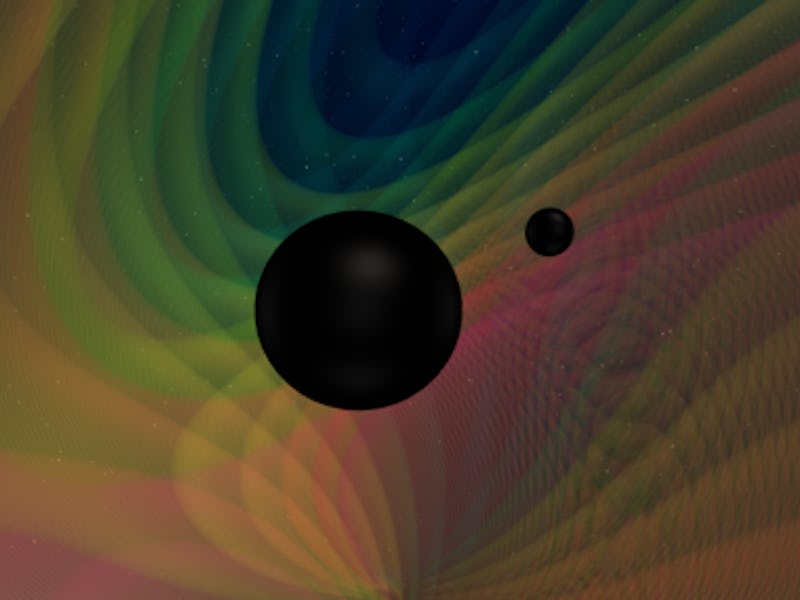

A simulation of a black hole merger between black holes of unequal masses.

Ever since scientists were able to detect gravitational waves in 2015, they have observed 10 of those black hole mergers. However, they have all been between black holes of similar masses.

"This is the first binary black-hole system we have observed for which the difference between the masses of the two black holes is so large!” Roberto Cotesta, a PhD student in the Astrophysical and Cosmological Relativity department at the Albert Einstein Institute in Potsdam, Germany, and co-author of the study, said in a statement.

The difference in mass between the two black holes resulted in more precise measurements of the binary system such as how far the black hole system is from Earth, the angle from we look at its orbital planet, and how fast the black hole spins around its axis, according to the researchers.

It also resulted in overtones in the gravitational wave signal that are much louder than usual observations of this kind, one that scientists had not been able to hear before.

Gravitational waves of higher harmonics, that are two to three times higher than the regular frequency observed so far, were predicted by Einstein's theory of general relativity. However, they had not been observed until GW190412.

The new observation also provides new insight into the mysterious activity of black holes, and how these unusual pair-ups may be taking place more frequently than scientists previously believed.

"We have observed the tip of the iceberg of the binary population composed of stellar-mass black holes,” Alessandra Buonanno, director of the Astrophysical and Cosmological Relativity department at the Albert Einstein Institute, and co-author of the study, said in a statement.