20 Years Ago, the Tony Hawk Games Pulled Off a Radical Reboot

Tony Hawk's Underground used skating subculture to inspire the masses.

Early 2000s pop culture was defined by three significant pillars: Beyoncé, Ryan and Marissa’s Orange County romance, and the Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater series’ beautiful ebb of chaos. Neversoft’s mission to create an interactive gateway for skateboarding manifested into four main titles from 1999 through 2002, turning a simple trick system with analog stick movement and button inputs into an alternative culture phenomenon. Skating wasn’t just a way of life — it was a sanctuary, an adrenaline fix, and a coping mechanism.

“I was amazed that the game ever transcended just skaters being interested in it because, at the time, skateboarding was still pretty underground,” famed skateboarder Tony Hawk explained in a recent oral history of the original title’s headbanging soundtrack. “To base a game on a sport that wasn’t popular didn’t seem like it could be a success. I just wanted to inspire skaters to buy a games console. That was the goal for me, because I thought they would appreciate the authenticity. But what ended up happening was it inspired a whole generation of gamers to try skating.”

But the best was yet to come. In October 2003, with an entire counterculture waiting in the queue, Tony Hawk’s Underground was born.

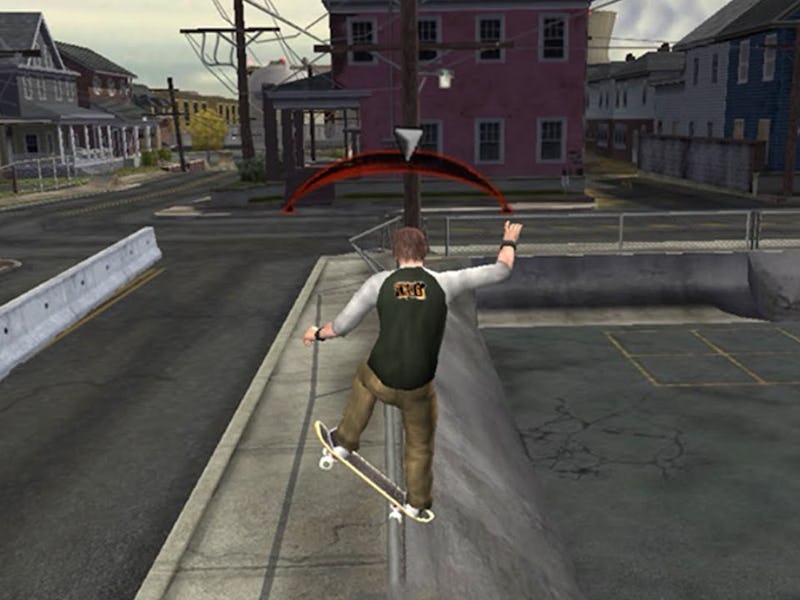

Neversoft axed the Pro Skater series’ time trials formula and improvised with a refreshed suite of mechanics. Underground still lived by manuals, reverts, and spine transfers, but it added wall plants and acid drops, extended controls with pressure flips and double tap grind tricks, and introduced an off-board system called “Caveman” that allowed players to explore levels by foot (or vehicle). But that was just the tip of the halfpipe.

Tony Hawk’s Underground still had secret skaters (Iron Man, Gene Simmons) and a much more detailed level editor, but it added two innovative concepts that pushed the franchise from pure (extreme) sports simulator into the role-playing genre: a Create-A-Trick system and expanded character customization. The new Create-A-Trick interface used similar technology to MTV Music Generator in which six rotations and trick elements can be remixed to alternate, modify, and combine separate moves.

Meanwhile, THUG’s character customization wasn’t a revolutionary step forward, but it was part of the project’s larger pursuit of creative freedom. The game encouraged players to project themselves into the protagonist's role. A special feature even used face-mapping to allow players to email a photograph to faces@thugonline.com and create a digital avatar of themselves for the PlayStation 2 version. But this was all a precursor to the game’s groundbreaking Career Mode.

Underground’s Career Mode feels directly inspired by classic skateboarding movies like Dogtown and Z-Boys and All the Streets Are Silent. The story follows your protagonist’s journey from amateur to pro, sparked by a surprise Chad Muska demo in suburban New Jersey that takes you to locals-only skate spots in Hawaii, San Diego, and Vancouver. It’s a seven-hour affair fueled by contests, the “soul skating” videos, and overarching themes of betrayal and redemption. (Your protagonist’s friend-turned-rival Eric Sparrow deserves a spot in the video game villain Hall of Fame.)

Eric is basically the Ganondorf of the Tony Hawk video game universe.

THUG’s individualism stemmed from Neversoft’s mission to encourage diversity and inclusivity. Instead of making a game all about A-list skaters like Tony Hawk and Bam Margera, Underground became a time capsule for skateboarding’s DIY heroes, showcasing pioneers (Bob Burnquist, Rodney Mullen) and new blood (Mike Vallely, Paul Rodriguez). It was also the last entry in the original series to feature Bucky Lasek, Steve Caballero, Jamie Thomas, Elissa Steamer, and Kareem Campbell. And there’s a laundry list of skate companies to endorse and five sponsors to ride with, Birdhouse, Element, Flip, Girl, and Zero, and each represents a different ideology, whether it’s connecting generational gaps, carving ramps overlooking Philadelphia, or the reality that “everything sucks.”

Then there’s the soundtrack. Tony Hawk’s Underground picks up where the series left off with a three-hour mix that shuffles through Refused, Bad Religion, MF DOOM, and odes to East Coast boom bap, 90s-tinted alternative metal, and skater subcultures of hardcore punk.

Caveman Mode turned Tony Hawk into an open-wold sandbox.

Underground’s commitment to immersion could have been a hindrance, but it steered the series into a bold new direction with endless possibilities. THUG 2 ushered in the Viva La Bam era with “sticker slaps.” American Wasteland went hot pink with emo renditions of Minor Threat and Gorilla Biscuits. And while Project 8, Proving Ground, and Ride weren’t perfect realizations, Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 1+2 was a Vicarious Visions remake that modernized Neversoft’s old handling code and geometry and earned praise for endorsing both diversity and representation.

Even with sequels being an afterthought (for now), it’s clear Tony Hawk’s Underground was a pivotal turning point for the series. Expanding the Pro Skater formula and embracing the notion of an RPG adventure allowed Neversoft to reshape its beliefs and philosophies, merging personalization with player autonomy to provide artistic freedoms free of limitations. Blending style and individuality is a practice that’s become standard with live service models, whether it’s Riot Games’ focus on accessibility or Respawn celebrating Women’s Equality Day. And it continues to redefine immersion and address why inclusive gaming matters.