It’s Ex Machina’s World. We’re Just Living In It.

“It’s Promethean, man.”

It’s eerie watching Ex Machina in the 2020s. Science fiction has always had a knack for predicting the future, usually for the worse, and Alex Garland’s cynical directorial debut is about as dark as they come. When Oscar Isaac’s crude tech billionaire, Nathan Bateman, muses about the inevitability of AI, it no longer feels like an empty prophecy, a problem for our kids to worry about. When Caleb Smith (Domnhall Gleeson), the programmer sent to test his most advanced AI yet, ends up falling in love with it, it’s harder to feel sympathy.

A story that once was far-fetched and fantastical is practically our reality. Artificial intelligence has society in a chokehold: a handful of Nathans are now actively running the world, while thousands of Calebs are falling right into their trap. What’s more, the trap isn’t nearly so enticing as the one that Garland conceives. Ex Machina, at least, has Ava (Alicia Vikander), a beautiful android who’s far smarter than she seems.

Ava may bear a striking resemblance to Sophia the robot, but she’s got a lot more in common with a Terminator. The latest evolution in a long line of androids, Ava is perfectly sentient — aware of her own existence, the man who created her, and the cage he placed her in. Nathan has no illusions, or even much humility, about his capacity to create either. In one breath he calls himself a god; with the next he likens himself to Ava’s dad. That’s partially why he needs Caleb, who’s been working as a grunt at Nathan’s despotic tech company, Blue Book. He plucks Caleb out of obscurity to run something called the Turing Test with Ava.

Within the walls of Nathan’s remote cabin-cum-research-facility, Caleb is instructed to perform a series of interviews that should determine Ava’s level of consciousness. Does she really have a soul, or is she just pretending to, projecting the idea of what a person should be? She’s a bit too advanced for a straightforward test, which prompts more intimate sessions between them. Before long Caleb decides not only that Ava can pass as a person, but that she deserves much better than a life under Nathan’s thumb.

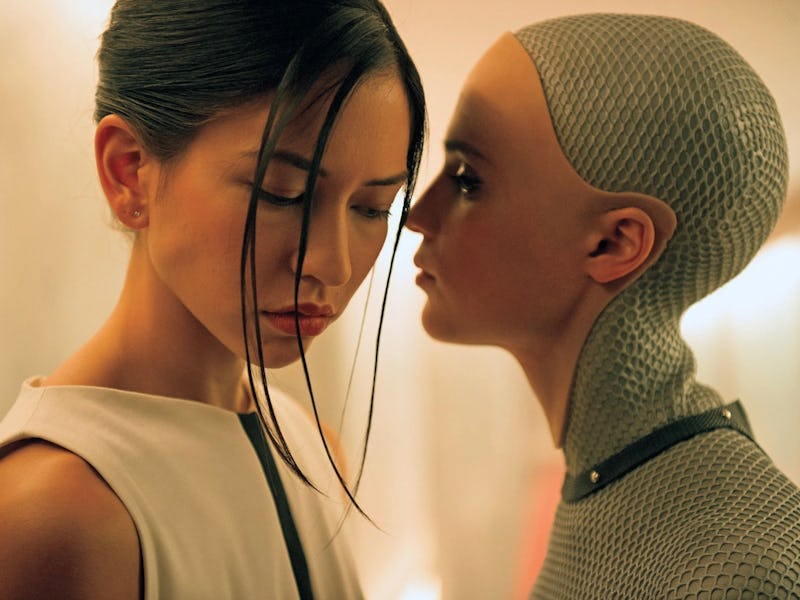

The case against Nathan clicks rapidly into place. A consummate alcoholic, his charm runs out quickly, and his sketchy research only damns him further. He treats Ava, the less-advanced Kyoko (a silent, yet striking Sonoya Mizuno), and all the models that came before like playthings, prisoners, or objects for his own pleasure. He discusses the idea of their sexuality — a feature he made sure to build into his latest models — with a chilling kind of boredom. It’s all especially harrowing for Caleb, whose sentiments towards Ava are much more altruistic, even courtly.

Ex Machina remains an incredibly cynical look at our near future.

What makes Ex Machina so interesting is that it skewers the “Nice Guy” persona with as much conviction as it does its more obvious antagonist. It’s a film that gestures broadly to the exploitation of women from a sci-fi angle, and it’s not the first to do it — nor will it be the last. But it also has the guts to ask if someone like Caleb, the white knight, isn’t also complicit in that exploitation. Ex Machina is trademark Garland in that no one is too pure to face judgment, and through a feminist lens, it’s almost cathartic. Nathan and Caleb are so preoccupied with the “Promethean” nature of this experiment, with men becoming gods or vice versa, that neither realizes they’re being played. Their hubris would be funny if that same story weren’t playing out on an even bigger scale in our own reality. There might have been a time where man outsmarted the machine, but now it’s their turn to play god.