The Worst Thing William Shatner Ever Made Was Accidentally Prescient

TekWar could never be made today, partly because we ignored its central message.

In sci-fi circles, making fun of William Shatner is perhaps, a little too easy. Whether he’s flying in space with Blue Origin, singing in his very specific way, or co-writing books, Shatner’s pure Shatner-ness is much bigger than his famous role as Captain Kirk in Star Trek. The list of sci-fi projects Shatner has been involved with includes a few franchises that contemporary science fiction fans may have forgotten, or possibly never heard of in the first place. Perhaps the most critically derided of Shatner’s post-Star Trek projects was the series TekWar. But 30 years after its January 17, 1994 premiere, this corny cyberpunk series is brimming with prescience and contemporary relevance — whether it was intentional or not.

In January 1994, the critics were not kind to TekWar, despite the fact that the debut TV movie had above-average ratings in both the US and Canada. Entertainment Weekly infamously called it “Dullbladerunner,” and critic Ken Tucker wrote, “In this vision of the future, your house can be invested with enough artificial intelligence to tell you when your wife left to run errands, but society still hasn't found a cure for crime.” But it’s here, in this critique that critics and audiences of 1994 possibly missed out on the one thing TekWar got right: It accurately predicted a future in which different technologies are omnipresent in everyday life, and the ethics of augmented and digital reality is hotly debated.

WTF is TekWar?

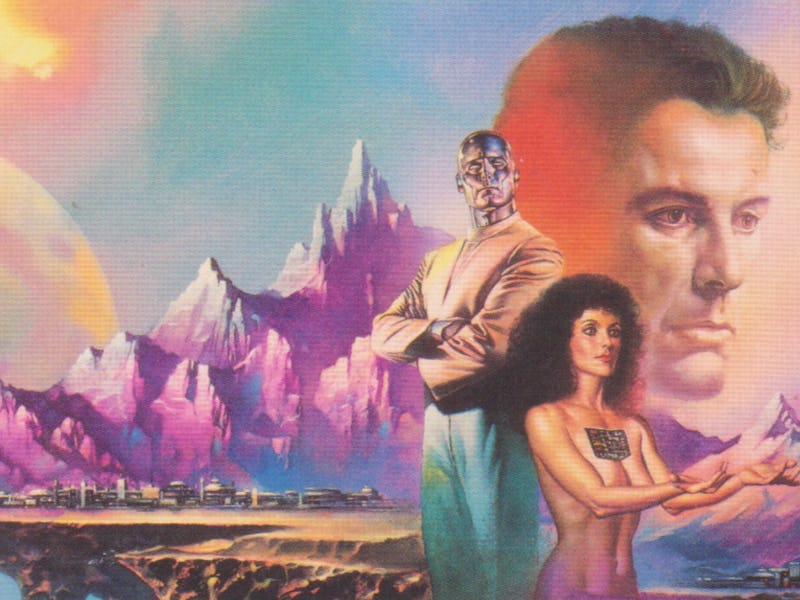

William Shatner promoting TekWar in 1994.

TekWar first came into existence when William Shatner had free time on his hands during the 1988 WGA strike. His vision was to write sci-fi crime novels that could blend his work on the cop show T.J. Hooker with, of course, his Star Trek cred. The result was the 1989 novel TekWar, with Shatner’s name on the cover, based on his notes, but ghostwritten by Ron Goulart. The premise is all about a near-future (the 22nd century in the novels, 2044 in the TV show) in which a specific type of virtual reality, called “Tek” has been made illegal due to its addictive and reality-altering properties. The hero of the stories is Jake Cardigan (Greg Evigan), a cop who used to track down Tek dealers, but is put in a cryo-prison for supposedly dealing Tek, even though he really didn’t.

In the first TV movie, Jake is recruited by a security guru named Bascom, played by William Shatner. Bascom promises that he’ll help clear Jake’s name if Jake solves various mysteries for him. None of these plotlines or the various low-rent villains are nearly as interesting as the casual assertion the entire series makes: Souped-up virtual reality is defined as a criminal narcotic! The narrative essentially imagines a world in which too much screen time becomes illegal. And it’s here, on a basic philosophical level, that the show is way more interesting today, even if it is tough to sit through.

What TekWar gets right (and wrong)

TekWar could never be made today.

Laughing at the clunky technology of TekWar is like making jokes about Shatner — it’s intellectually lazy. Yes, the giant videophones are silly, but we let Blade Runner get away with that stuff because it had style. Sci-fi isn’t supposed to accurately predict the future anyway, so giggling at all the silliness of TekWar’s production design is ultimately a question of aesthetics, rather than content. To put it another way, TekWar fails as a piece of art, but it succeeds at floating a thought-provoking premise that makes more sense now than it did then.

Throughout its two seasons, TekWar employed several great writers of sci-fi TV, notably, Morgan Gendel, Hans Beimler, and Marc Scott Zicree. These Star Trek alums clearly did their best with the trappings of TekWar, which is why, underneath its low-budget-movie-of-the-week quality, there’s some legitimately good sci-fi writing in the show. What is the limit of data manipulation? What is the line in which virtual reality addiction can be defined as criminal? You could call TekWar a bad version of Strange Days or a soap opera TV version of Johnny Mnemonic (in the early 1990s, trading illicit data discs was all the rage) but when you look at the actual ideas in the series, it’s somewhat shocking that you can’t imagine the show ever being made today. Not because we think the technology is silly or unrealistic, but because the moral premise of the show simply would not resonate with anyone living in 2024.

The cast of TekWar, is here to get your brain off of... something that would be totally legal today.

The biggest question of the series is: If Tek is just a very convincing type of virtual reality... why is it illegal? The answer to that question is interestingly much more complex than it seems. In 1994, you could safely put all debates about data authenticity or fake news into the realm of science fiction, conspiracy theories, or the occasional news story about how good crooks were at making fake credit cards. The idea that data or virtual technology could be so good that it would require regulation seemed far-fetched. This wasn’t because we didn’t value authenticity in 1994, we simply didn’t believe augmented reality, virtual reality, or AI would ever work that well.

The idea here is basically a reversal of ethics in Ready Player One: Everyone could get so hooked on non-real things, digital simulations, and information, that they cease to function in the real world. In Ready Player One, that’s just the coolness of the Oasis. In TekWar, that same technology is treated like heroin or meth. Essentially, Shatner’s series asserted what now feels like an old-fashioned paradigm: real life matters.

And yet, as real-life AI bots create non-authentic data “hallucinations,” the question of what constitutes an authentic reality gets more slippery. TekWar strongly asserts the idea that an utterly convincing, semi-telepathic simulation has inherent moral harm. Today, there’s plenty of hand-wringing about the addictive nature of nearly all non-analog technologies. But, it’s not as if the average person takes this seriously. The sci-fi premise of TekWar assumed that data manipulation and addictive digital technologies would somehow feel apart and other from our day-to-day experiences. This, of course, is not what happened. Because, in real life, we lost the TekWar before it even began. Or maybe we won?

TekWar only streaming on YouTube.

This article was originally published on