Guillermo del Toro's Biggest Blockbuster Remains a Surprisingly Soulful Masterpiece

Monster fighting should leave a little room for love.

The premise of Pacific Rim is silly, but any film that features giant, city-stomping monsters — and introduces equally-massive mechs built to take them down — demands some suspension of disbelief. Despite its light-hearted premise, it’s earned a shocking amount of reverence in the decade since its release.

Even by today’s standards, Pacific Rim is a rare beast. It’s a standalone sci-fi with a heartfelt, humanist message, but it doesn’t skimp on the bruising, bare-knuckle action. It’s a rare blockbuster without any ties to superhero franchises or other preexisting properties, it features a diverse, international cast, and it even introduces some dizzying emotions to its rock ‘em sock ‘em monster mash. It’s a miracle it even exists, let alone that it turns such a superficial concept into one chock full of grace and emotional heft.

The premise of monsters and mechs — or, as they’re labeled in Pacific Rim, Kaiju and Jaegers — doesn’t always fit the mainstream. That didn’t stop director Guillermo del Toro and screenwriter Travis Beacham from crafting a thoughtful homage to both, and elevating a subgenre that Michael Bay had recently popularized with his Transformers saga. It helps that their Jaegers aren’t just sentient robots with remarkably-quick reflexes. Del Toro and Beacham ensure we feel the weight of each step and the heft of each blow thrown. More importantly, we understand why the Jaegers (or rather, the humans piloting them) are fighting in the first place.

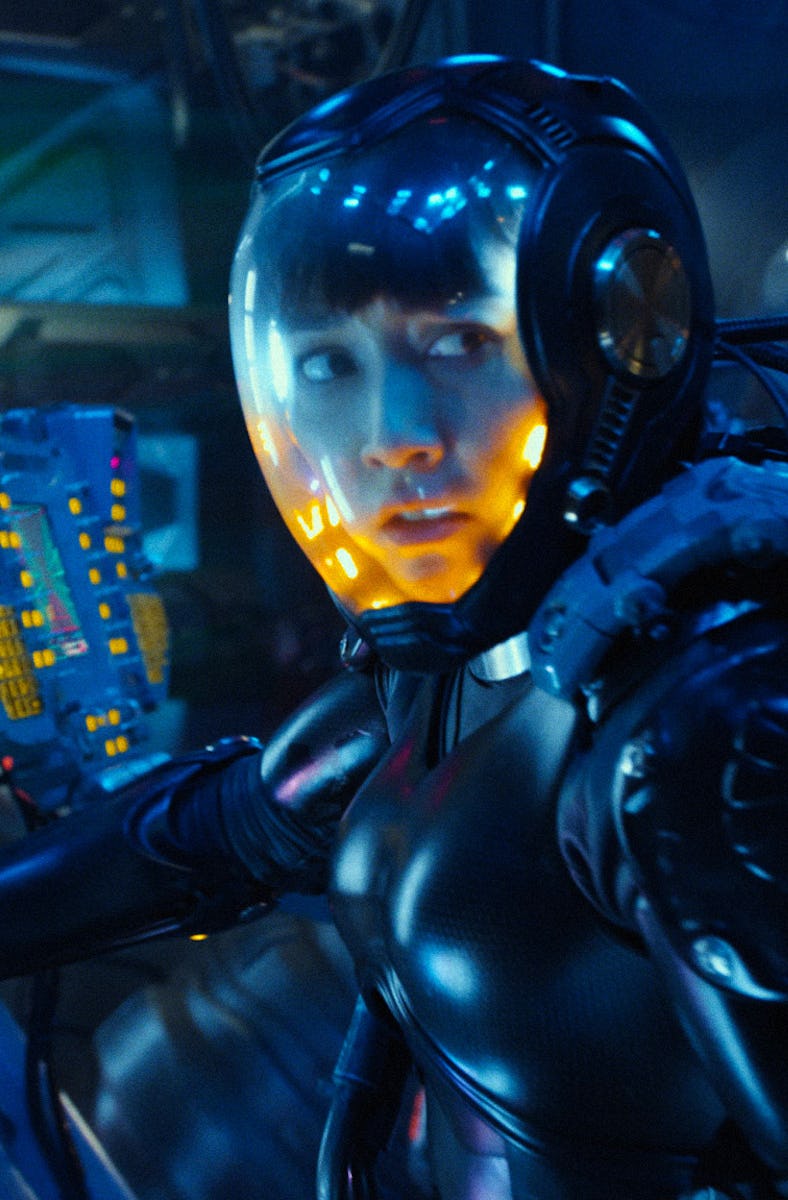

The mechs used to fight the Kaiju are just as massive as the monsters, and just as the Kaiju need two brains to move around, so do the Jaegers. That means two humans in the cockpit, piloting the mechs as they would their own bodies. These two humans need to be connected mentally and emotionally. They become one in the Drift, a neural bridge that allows them to share their consciousness — their instincts, memories, and emotions.

Drift-compatible pilots can be fathers and sons, siblings or twins. They can be married or chaste. They could be friends, or they could hate each other. None of that matters in the Drift. As long as your connection is strong, you’re capable of piloting a mech. We learn this through Raleigh Beckett (Charlie Hunnam), who joins the Jaeger Program to fight with his brother, Yancy (Diego Klattenhoff). Their first and last mission together establishes the importance of the Drift, but Del Toro wastes no time in depicting the horrors of a severed bond.

Yancy is killed by the Kaiju he and Raleigh are tasked with fighting, and Raleigh experiences all the agony for himself. It’s enough to turn him off from Drifting forever, but as the years pass and more and more Kaiju storm coastal cities, Raleigh knows he can’t hide on the sidelines forever.

Rinko Kikuchi, Idris Elba, and Charlie Hunnam lead Pacific Rim’s emotional journey.

Raleigh is pulled back into the fray by Stacker Pentecost (Idris Elba), the leader of the dying Jaeger Program. Raleigh is the last pilot Pentecost would ever turn to for help, and he definitely doesn’t want Raleigh Drifting with his adopted daughter, Mako Mori (Rinko Kikuchi). But their compatibility is the one thing out of his control, as Mako and Raleigh can’t help but be drawn together. Their dynamic isn’t quite romantic, but it’s certainly not platonic. Like so many of the relationships depicted in Pacific Rim, it’s too intimate to describe. Once you’re in someone’s head, living their memories and experiencing their trauma, the labels we use to define relationships aren’t really enough.

There is no real romance in Pacific Rim, but there is love. Love is the very thing powering these Jaegers and allowing our pilots to save the world. It’s just not the kind of love we’re used to seeing, especially in such action-forward adventures. Pacific Rim does away with the kind of romantic subplots that could derail the story, instead beefing up all the film’s broader relationships. These aching, emotional bonds coexist perfectly with Pacific Rim’s bruising world. Action and feeling complement each other, which is exactly what makes a good story work.

The idea that Del Toro and Beacham would craft such an earnest fantasy technology for what is essentially an anime-inspired schlockfest is, again, kind of silly. But it remains one of the film’s best features, and one of the best sci-fi inventions of the 21st century. It’s not the only element that makes Pacific Rim great, but it allows the film to transcend the tropes it’s adapting. Ten years on, Pacific Rim is a blueprint for how sci-fi doesn’t need to feel self-conscious about wearing its heart on its sleeve.

This article was originally published on