The Sixth Sense Is Ultrasonic Touch and the Seventh Is 360-Degree Vision

Our senses limit our exposure to the world. Inventors will change that -- soon.

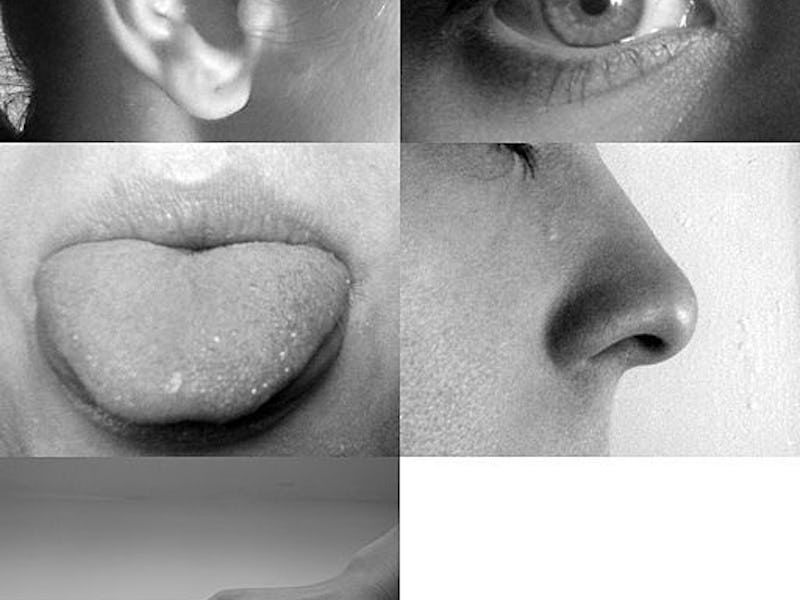

We use our five senses — touch, sight, smell, taste, and hearing — to draw information from and make sense of the world around us. But our biology limits what we are able to perceive. Put another way: Our out-of-the-box functionality is limited. We don’t smell radio signals, see in infrared, or feel gamma rays. We’re ignorant of what’s behind us and capable of touching only what we can reach. We are, in short, human. But that’s no longer a simple truth. Today, humanity has ceased to be a state of being and become something closer to a spectrum. What do we make of the woman who recently had retinal chips implanted at Oxford Eye Hospital and can now see? She’s not inhuman, but she’s human+.

And there’s plenty of reason to suspect that we’ll all be joining her. Technology has plenty to offer people with their sensory organs in tact. There are new ways to harvest information from the world around us that will enhance the human experience by elaborating on it. We will, in short, augment reality by gifting ourselves new sense. We’re already moving that way.

In an explanation of his currently shelved SixthSense project, Pranav Mistry, now Global Vice President of Research at Samsung, wrote: “Arguably the most useful information that can help us make the right decision is not naturally perceivable with our five senses, namely the data, information, and knowledge that mankind has accumulated about everything and which is increasingly all available online.” The sixth sense we need, he argues, is a link between our digital devices and our interactions with the physical world.

Whether or not we need an extrasensory interface or not, it’s the sixth sense we’re most likely to get. It is, after all, the sense that would allow for the most growth within the personal tech industry. In fact, this new power may be available in about two years.

Tom Carter, co-founder the United Kingdom-based Ultrahaptics, began his career in touch technology working as a researcher at the University of Bristol, where his team developed an ultrasound-based haptic interface technology in 2013. The way this works is relatively simple: Ultrahaptics’ technology uses ultrasound to create sensations in the air that can be felt by the user, allowing people to feel what’s on an interactive service (like an iPad) without seeing it. A series of ultrasonic traducers emit high frequency sound waves that, when they all meet at the same location, create sensations that can be felt on skin. The tactile properties of the focal points can be varied, allowing the sensations to feel differently in different spaces.

“Imagine a toaster you can control by making a gesture near it, and getting a lever-life sensation on your fingertips,” said Carter to Wired UK this December. “According to what the tracker sees, we can update the ultrasound makes you feel.” Carter and his company are currently being courted by car, consumer electronics, and gaming companies for access to this technology. He says that Ultrahaptics will be incorporated into these often-tapped industries sooner tha the average person realizes.

But is it a sense if it’s built into our technology rather than ourselves? Yes and no. As next-generation haptics are introduced they’ll provide a very cool interface. As they become ubiquitous, they’ll become a sense in that the interface will be part of the world and thus interacting with it will be part of our experience of the world. There’s also the possibility of reverse engineering the technology. Something wetwear body hackers have been trying to do with field-sensing implants for years.

The extrasensory technology developed by neuroscientist David Eagleman is unlikely to be ubiquitous within this decade, but it provides an arguably more exciting look into the way we can develop new sense by piggybacking on the old ones. Director of the Laboratory for Perception and Action at Baylor College of Medicine and part of the team at the electronics developer NeoSensory, Eagleman is focused on creating a sensory substitution for the deaf. He and his team created the Versatile Extra-Sensory Transducer, also known as the VEST. Worn like a vest (try to keep up), the device allows the deaf to “feel” speech — it captures sounds by a tablet or smartphone and then is mapped onto a vest covered in vibratory motors. Sounds are translated into patterns of vibrations users can be taught to interpret.

“The patterns of vibrations that you’re feeling [while wearing the VEST] represent the frequencies that are present in the sound,” Eagleman told The Atlantic. “What that means is what you’re feeling is not code for a letter or a world — it’s not like Morse code — but you’re actually feeling a representation of the sound.”

David Eagleman and the VEST.

Eagleman’s focus has been on providing deaf people with a tool, a noble goal to be sure. But the VEST technology may have broader ramifications. The fact that the VEST allows people to interpret sound information arriving from all directions serves as proof of concept for other applications. Eagleman, who described this as a “new kind of human experience” in his TED talk, has suggested linking the garment to Twitter or other information streams. That proposal makes sense, but the more obvious everyday use case might well be sonar. If the vest could translate sonic information about locations to the vest, it could essentially provide a new way for humans to experience sense of place, an experience similar to being a dolphin or bat.

These new senses won’t arrive immediately and their early iterations will likely come with bugs, but they point to the sorts of ways we can train ourselves to understand the world around us in greater detail. For now, they’ll offer new senses by augmented our old ones, but the ultimate goal is to have the interface be mental — to further wire the world into our brains. Our humanity, after all, isn’t exclusively a product of our limitations.