Train like an astronaut -- a better way to cope with cancer

Copying how astronauts prep for spaceflight could help people on Earth handle chemotherapy.

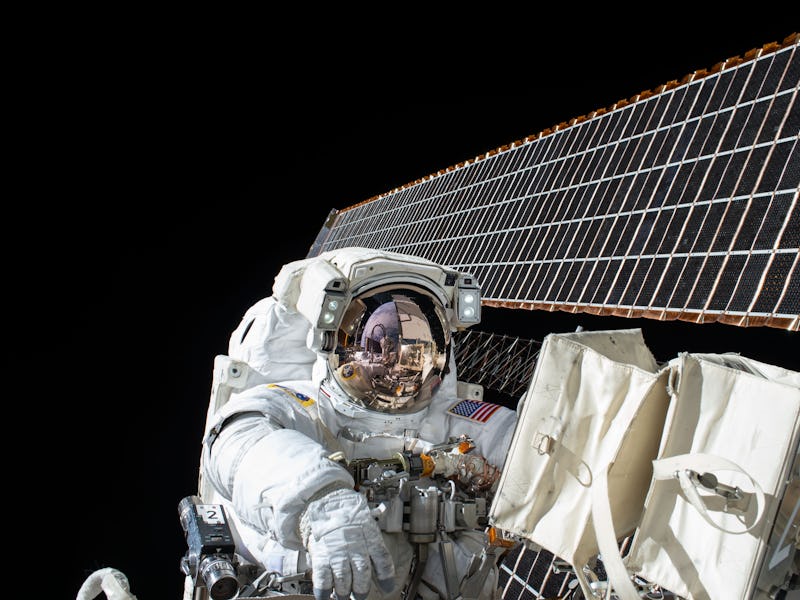

Spaceflight takes a toll on the human body. Astronauts experience changes in how their heart functions, loss of muscle mass, and ‘space fog,’ or difficulty focusing.

And while they may be separated by millions of miles, another group of people experience very similar effects. The side effects cancer patients experience when undergoing treatment is oddly reminiscent of the effects of spaceflight. But instead of ‘space fog,’ they call the same trouble focusing ‘chemo brain.’

But despite the similarities, each group receives very different instructions on how to care for their bodies.

Now, a study suggests that the exercises prescribed by NASA to astronauts before, during, and after spaceflight might be useful for mitigating the effects of cancer treatment here on Earth. The study was published this week in the journal Cell.

Known as the Human Health Countermeasures program, the NASA regimen includes physical fitness drills and exercises for astronauts designed for the period before they embark on their journey to space and while they are in the microgravity environment. The program also helps to rehabilitate them once they return to Earth. The exercises include strength training and daily running drills — both on land and on special treadmills installed on spacecraft.

Healthcare lessons from NASA

The program helps astronauts manage the effects of microgravity on their bodies, and NASA credits it with helping them live in that environment for an average of six months.

Such intense physical activity is rarely prescribed as part of cancer patients’ regimens, however.

A new paper suggests exercises based on NASA's regimen for its astronauts could help cancer patients.

“That’s completely backwards to how it is on Earth, where cancer patients may still be advised to rest in preparation for and during treatment, and may have to ask permission to exercise from their physicians,” Jessica Scott, an exercise physiology researcher at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center’s Exercise Oncology Service, and lead author of the study, said in a statement.

"It’s a wonderful idea, a beautiful aspiration for cancer care."

The paper offers an alternative: an exercise program for patients undergoing treatment based on NASA’s microgravity countermeasures program. The authors urge cancer patients to exercise before, during, and after their treatment.

Kathryn Schmitz, a researcher at Penn State University College of Medicine who was not involved in the study, says that there is a growing body of evidence that exercise and nutrition can help people undergoing cancer treatment — but it is rarely implemented in reality.

“Why do we have evidence, and it hasn’t changed practice?” Schmitz says.

In line with her approach, a set of international guidelines, released in October this year, also recommends that people who have had cancer in the past perform aerobic and resistance training for 30 minutes, three days a week.

To make a change, people need to be more aware of the benefits exercise can have for people with cancer, says Schmitz. Hospitals also need to change in order to accommodate this type of intervention.

But beyond that, there needs to be a change in policy, she says.

“In cancer, as with different types of medical issues, there are clinical guidelines that need to be followed,” she tells Inverse. “If there’s no guideline that says we need to have pre-habilitation, then why do it?”

Could astronauts’ prep actually help cancer patients?

While the new paper presents an interesting analogy between astronauts and cancer patients, she says, there are some caveats.

“People who are astronauts have chosen to be astronauts, people who have cancer did not choose to have cancer,” she says. “They find themselves in a situation that is out of their control, and that’s an important difference.”

Hospitals and community cancer centers generally fail to accommodate patient exercise. NASA facilities, on the other hand, are much better equipped, Schmitz says.

Also, there are just a lot more people living with cancer than there are astronauts. More than 1.7 million people arediagnosed each year in the United States — that makes it more challenging from a resource standpoint to accommodate physical training.

“It’s a wonderful idea, a beautiful aspiration for cancer care,” Schmitz says.

Schmitz has some practical, easy-to-implement guidelines for people undergoing cancer treatment that could help them cope with its side effects. They can go to their cancer center’s dietician to help them increase their protein intake and so increase muscle mass. They can also take up walking or jogging for 30 minutes two to three times a week, and do some bodyweight resistance training at home or a gym if they have access to one.

“Waiting until you get the ideal program is the wrong idea,” Schmitz says. “Doing something is better than doing nothing.”