Helen Rodríguez Trías: 6 Bold Quotes on the Necessity of Women’s Healthcare

She challenged the sexism, racism, and classism that women face.

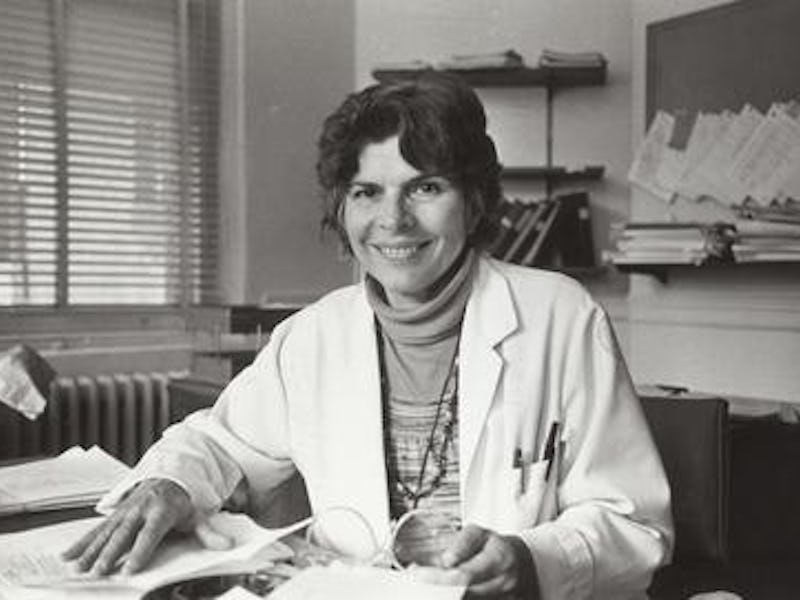

As a physician, Helen Rodriguez Trias established health centers and practices that served women and children from underprivileged communities. As an activist, she was one of the most vocal leaders in challenging dubious medical practices that further disenfranchised the patients she served. With healthcare and abortion rights being hotly contested issues today, Rodriguez Trias’ decades-old statements on the future of women’s health remain all too relevant.

Rodriguez Trias’ tireless efforts were celebrated in a Google Doodle on Saturday, honoring what would have been her 89th birthday.

Helen Rodríguez Trías Google Doodle

“What brought me to the women’s movement was the women’s health movement,” Rodriguez Trias is famous for saying, but that quote doesn’t end there. In the full context of that quote, discussed by Joyce Wilcox in the American Journal of Public Health, she continues:

“The cultural elements of feminism didn’t resonate with me, but abortion resonated with me. I became part of the women’s movement in October 1970 at an international meeting on abortion rights attended by several thousand women and held at Barnard College in New York City.”

Rodriguez Trias’ frank discussions on women’s health would equip both doctors and activists to acknowledge the disparity between wealthy and low-income women and the additional challenges facing women of color as they navigate the US healthcare system. Her words echo in today’s political discourse over women’s bodies and serve as a jarring reminder that these discussions must still be had.

Rodriguez Trias Addressed Inequality in the Industry

“I think my sense of what was happening to people’s health was that it was really determined by what was happening in society — by the degree of poverty and inequality you had.”

Rodriguez Trias worked in the United States, Central and South America, Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, but throughout her international work, she continued to see a direct link between a woman’s income and her access to the full amount of health rights and health advancements available to her. This is one of the reasons why she became a founding member of the Women’s Caucus of the American Public Health Association in 1971, which explores women’s experiences while considering the intersection of economic, cultural, sexual, political, and environmental forces.

Women Dying From Botched Abortions Caused Her to Act

“I saw that anybody who could afford an abortion could get a perfectly fine one. It would be written up as an appendectomy. Women from the US used to go to Havana to get abortions. […] If a poor women needed an abortion, she came to the University Hospital in the middle of the night and said she had fallen and was having a miscarriage.”

After Rodriguez Trias established the first center for the care of newborn babies in Puerto Rico at the University Hospital in San Juan. During that time, she bore witness to the differences in how low-income and wealthier women acquired abortions and how that disparity often dictated the success of the procedure. She struggled to provide care to women who had attempted their own abortions, which sometimes resulted in the woman’s death.

She Confronted Racism in Healthcare

“We got a lot of flack from White women who had private doctors and wanted to be sterilized. They had been denied their request for sterilization because of their status (unmarried), or the number of their children (usually the doctor thought they had too few). They therefore opposed a waiting period or any other regulation that they interpreted as limiting access . . . While young white middle-class women were denied their requests for sterilization, low-income women of certain ethnicity were misled or coerced into them.”

In 1937, a law in Puerto Rico had gone into effect that called for the legalized sterilization in order to control the island’s overpopulation. Women who were forced or coerced into sterilization were then test-subjects for reproductive research. In 1974, Rodriguez Trias and her colleagues formed the Committee to End Sterilization Abuse to write guidelines for better sterilization practices, which were implemented in 1978.

She Amplified Diverse Voices Within the Industry

“I began to understand that we were coming to different conclusions because we were living different realities. The women’s movement is heterogeneous; people have different perspectives. The women’s movement has been successful only to the extent that it shares experience, finds common ground, and fights for the same thing.”

Seeing the disconnect that was alienating women within the healthcare profession, Rodriguez Trias created spaces in the Bronx throughout the 1970s for women to share their experiences in a way that doctors could better serve their communities. Thanks to her nuanced approach to working with women and families of all backgrounds, she became the first Latina to be elected president of the American Public Health Association in 1993.

Looking back on her extensive career, Rodriguez Trias emphasized that listening to women of all economic, social, and racial backgrounds is the best way to ensure that their medical needs are met. “I am proud that I made my contribution in moving forward that dialogue among many women, a dialogue that took place over many years,” she said. “We had to listen to each other; we had to find out each other’s reality.”