Evidence of Martian Life Is Likely Under the Crust, Say Scientists

It's time to dig a little deeper.

While the United States government tries to figure out whether alien life is out there zooming around on UFOs, scientists are attempting to figure out whether life could actually have existed on Mars. Understanding the conditions that would be necessary for Martian life, they argue, could explain how life began here on Earth.

Unfortunately, previous efforts to find life on Mars may have been misguided: In a new Nature Geosciences article, an international team of scientists, including two from NASA’s Johnson Space Center, argue that the best chance at encountering evidence of Martian life isn’t examining what’s at the surface — but rather what’s underneath it.

There’s a possibility that “the abundant hydrothermal environments on Mars might provide more valuable insights into life’s origins,” the researchers write. Mars, they explain, is the only object in the solar system with an ancient and well-preserved crust, and in this crust is “clear evidence of water-rock reactions dating to the time when life appeared on Earth.”

And as Paul Niles, a planetary geologist at NASA’s Johnson Space Center, said in a statement in October, sometimes all life needs is “rocks, heat, and water.”

The best chance of finding evidence of Martian life is looking under the crust.

Because our planet’s early geological record is so poorly preserved, some scientists argue that the best way to figure out how life began on Earth is by looking at “cradle of life” chemical systems on other planets. Currently, we have a limited understanding of how life emerged on Earth over 3,800 million years ago and rely primarily on laboratory experiments and theories to explain how we all came to be.

“There is a growing interest in the possibility that terrestrial life originated not within an ocean environment, but rather in vapor-dominated geothermal systems, where shallow pools of fluid may have interacted with porous silicate minerals and metal sulfides,” the researchers write in the new paper.

Mars, which has an older and better-preserved geological record than Earth, is believed to have once had the hydrothermal conditions necessary for creating life. But these conditions weren’t present on its surface, as the planet lost its magnetic field 4,000 million years ago, exposing its surface to radiation and most likely destroying the possibility that photosynthesis could have evolved there. No photosynthesis and high radiation rates means that life would have been forced to emerge underneath the planet’s crust.

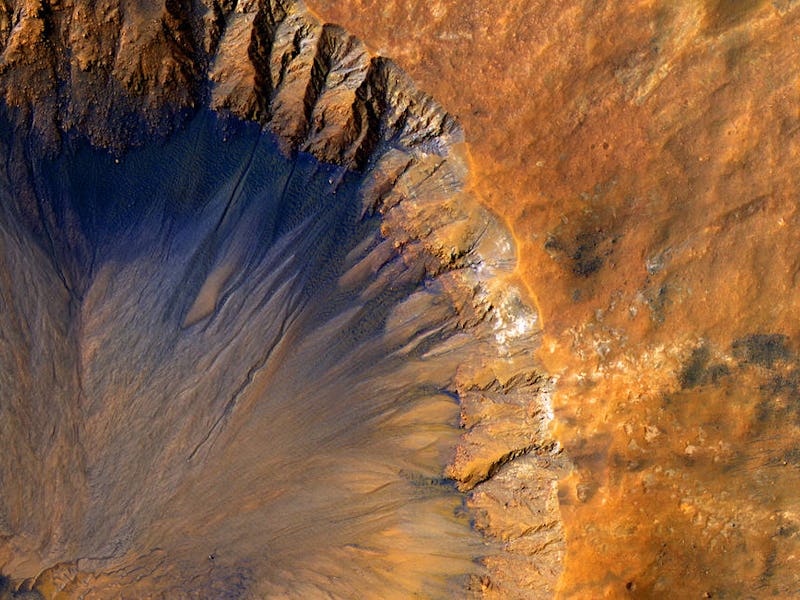

In October, NASA found evidence that the planet once contained hot springs that shot mineral-filled water into a giant sea, indicating that the planet once had ancient hydrothermal systems. Photographs taken by the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter revealed proof of that hydrothermal activity in the shape and texture of the bedrock layer in Mars’ Eridania basin, which suggested there was once fluid flow in the planet’s crust. It’s likely that in these places, the combination of volcanic activity along with standing water created the conditions necessary to create early forms of life.

How hydrothermal activity works.

In this new paper, the scientists also point out that in 2008 the Spirit Rover encountered soils and bedrock of nearly pure opaline silica, a mineral indicative of hydrothermal activity. This likely means there are still hydrothermal sites under Mars’ surface.

“Mars is not Earth,” the scientists write. “We must recognize that our entire perspective on how life has evolved and how evidence of life is preserved is colored by the fact that we live on a planet where photosynthesis evolved.”