Net Neutrality Wouldn't Save the Internet, Anyway, Says Former FCC Adviser

The FCC's decision Thursday is just one part of the problem.

David Farber says that when it comes to our freedom of speech online, the FCC’s decision Thursday is only one piece in a much greater puzzle.

“I wish that the debate had been more under the pros and cons of Title II, rather than this mystic net neutrality,” he tells Inverse.

Farber, 83, is a computer scientist and adjunct professor of Internet Studies at Carnegie Mellon. He served as the chief technologist to the FCC in 2000 and 2001.

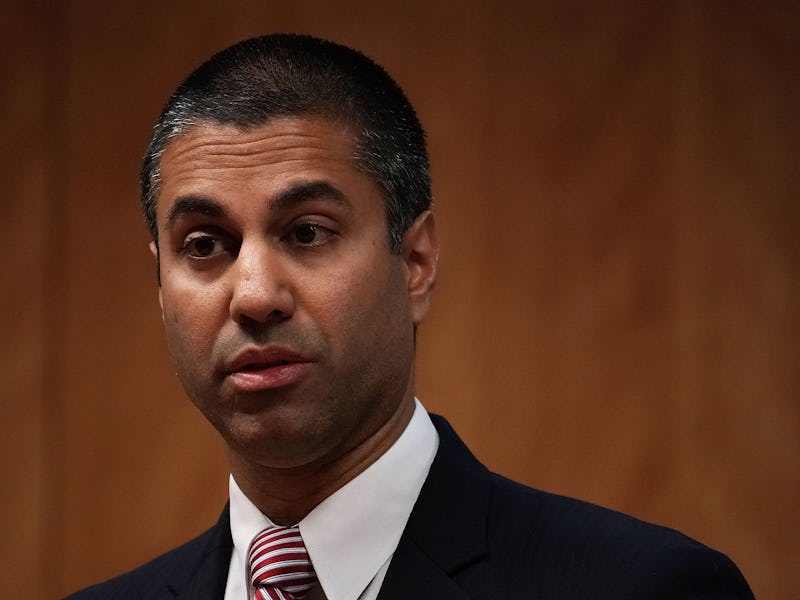

On Thursday, the FCC approved commissioner Ajit Pai’s plan to repeal Title II, a set of Obama-era regulations that classified internet service providers as common carriers. In other words, they were providers of a utility, and were prevented from charging different rates in order to access different parts of the web or use streaming services, and couldn’t give preferential treatment to streaming services or websites based on a fee. Now, that all might change.

But Farber isn’t very concerned about what big telecom providers like Comcast and Verizon might do now that they’re off the leash. “Remember they had the opportunity years before,” he says. “And there was no sign that they were going to do that. If you look historically at every case that I know of, the FCC has just looked at them and said, ‘That’s not right,’ and they just backed away.”

Farber is more concerned with what large internet platforms can already do. “We’re bypassing the real issues, which are: What powers do we give various agencies? How does it impact the future? How does it impact — if at all — the dominant services which I think are Facebook and Twitter. All of whom are completely exempt from this argument right now.”

As private corporations, social media platforms are allowed to set their own standards of use and best practices for their users. Farber is worried that the sheer ubiquity of these sites could impact free speech. What’s needed, he says, is new legislation that will properly regulate the internet.

“It’s a godawful mess,” he says. “What’s needed is for Congress to come in and re-do the laws to recognize that the old communication industry is dead, and that there ’ain’t no telephone service to speak of anymore, it’s all voice over the internet.”

Congress or no Congress, during Thursday’s FCC hearing, Democratic commissioner Mignon Clyburn, painted a very different picture than Farber as to what might happen under the FCC’s new plan.

“We will be in a world where regulatory substance fades to black and all that is left is broadband providers’ toothy grin,” she said, continuing the Alice in Wonderland reference. “And they have teeth. They will say those old comforting words, ‘Don’t worry, we have every incentive to do the right thing.’ But soon they will have the incentive to do their own thing.”

Democratic commissioner Jessica Rosenworcel echoed her statements. “They will have the power to block websites, the power to throttle service and the power to censor online content, they will have the power to discriminate and favor internet traffic from companies with whom they have a pay-to-play arrangement,” she said.

FCC Commissioner Mignon Clyburn at a December 7 protest for net neutrality.

To all this, Farber essentially provides a shrug. “They’ll try to push their weight, but I would hazard a guess that under Title II they’d try to push their weight also. They’re a huge lobbying organization in Washington,” he says.

“Title II, yeah it gives the FCC a lot of possibilities of enforcement, but it doesn’t have to take it.”

Farber is correct when he says that the FCC’s new plan — like the old one — is merely a set of regulations and not actual law.

Thursday’s decision is already set to be battled out in the courts, according to Wire:

Most immediately, the activity will move to the courts, where the advocacy group Free Press, and probably others, will challenge the FCC’s decision. The most likely argument: that the commission’s decision violates federal laws barring agencies from crafting “arbitrary and capricious” regulations. After all, the FCC’s net neutrality rules were just passed in 2015.

Farber’s also concerned that a revolving door of regulatory changes creates an uncertain arena for web companies and how they conduct their business. “I can almost guarantee if a Democratic president comes in we’re going back to Title II again,” he says.

For regulation that’ll stick, Congress is the only solution. Farber says that face to face meetings with lawmakers at town halls are some of the most effective ways to get a congress person’s attention. “It’s very hard, but an electronic sign up sheet doesn’t do much. And I’d know… they’re scored at the FCC and then nobody looks at them again. They look at what the companies say, but not what these individuals say.”

Leading up to Thursday’s vote, the issue of net neutrality managed to unite Democrats and Republicans alike — a rare feat in 2017 — and sparked protests across the country. If it falls on Congress to finally create some better protections that reflect our laws on free speech, Farber hopes service providers, like Facebook, Twitter and Google, are part of the equation.

“I think that what I would hope to happen is that we take a long, hard look outside the Congress initially, outside the government,” he says. “What is the regulatory authority we need over the internet as it exists, which is considerably more than just a wire.”

With reporting by Alasdair Wilkins.