The "Gender Crime" in 'Handmaid's Tale' Isn't Fictional

Reminder: The dystopia in Margaret Atwood's dystopia has roots in real life.

The first three episodes of Hulu’s The Handmaid’s Tale adaptation began streaming this week, introducing viewers to Margaret Atwood’s religious dystopia. In Atwood’s speculative, half-fictionalized world, the Republic of Gilead legally puts “gender criminals” to death, hanging their bodies where God-fearing citizens can see them. In the show’s pilot, Offred (Elisabeth Moss) and Ofglen (Alexis Bledel) silently study three bodies by the river, and Offred notes that one victim’s hood bears a pink triangle.

In her novel, Margaret Atwood adds queer people to the list of her fictional society’s victims alongside abortion providers, non-Christian religious leaders, and political rebels; the Republic of Gilead uses extremist Christianity in order to explain its murder of innocents. In Hulu’s adaptation, queer women are executed by Gileadean authorities, unless — as in the case of Alexis Bledel’s Ofglen — their reproductive systems work well enough to make them useful Handmaids. In reality — which Atwood drew straight from — many governments around the world sentence queer people to death or allow citizens to kill queer folk with legal impunity.

“As far as I was concerned, I was reflecting the world that already existed,” Atwood told The New Yorker in April about her novel, first published in 1985. “I didn’t do anything that people hadn’t already done, in other words, and therefore were quite capable of doing again. So I was reflecting the world; I wasn’t thinking it up, and to that extent I think it’s cathartic to write about those things that are real, and to put them out there.”

Offred and Ofglen study the dead in 'The Handmaid's Tale'

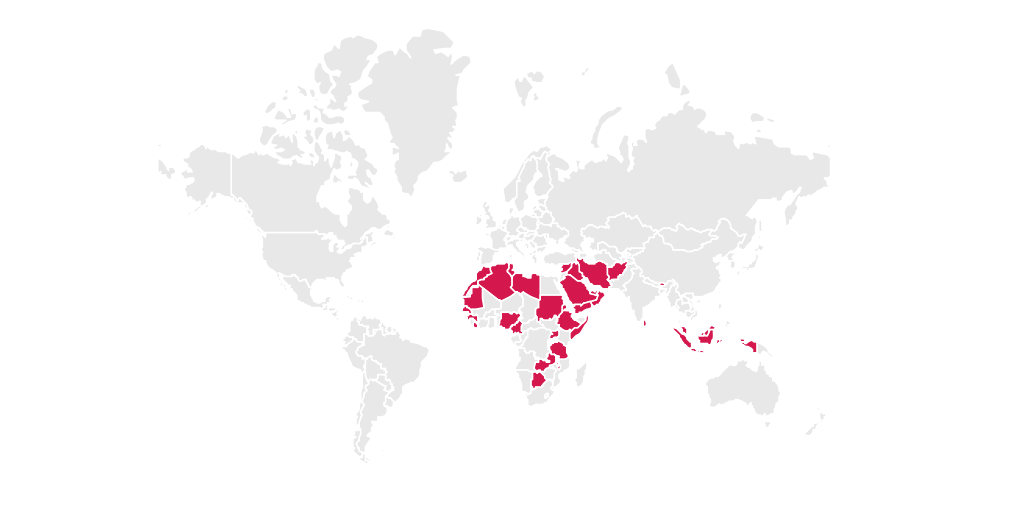

Where in the world Can You Be Killed for Being Queer?

As of June 2016, the ten nations which still put queer people — or those assumed to be queer — to death include Yemen, Iran, Mauritania, Nigeria, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Afghanistan, Somalia, Sudan, and United Arab Emirates. There are, of course, many more nations — The Independent reports 76 in total — in which homosexuality is illegal, though it doesn’t necessarily carry a death sentence. Queer men are most often the target of homophobic laws, though there is a disturbing rise in laws banning homosexual sex between women in recent years.

Notably, Sharia law and the inflexible adherence to Islamic extremism (note: not laws observed by all Muslims) is to blame for many of these inhumane legal practices, though it is by no means the only ideology behind the systemized murder of queer people.

In 2005, the Iranian government released a photo of two underage boys being hanged publicly for “rape,” which horrified an international audience. Mahmoud Asgari, 16, and Ayaz Marhoni, 18, were killed for allegedly raping other young men, though critics of the Iranian government were quick to point out that if the homosexual sex had been consensual, as Asgari’s and Marhoni’s families insisted it was, their partners would have to put themselves in danger in order to confirm this. At the time, it was much safer to tell authorities you had been raped by another man than divulge that you had engaged in homosexual acts by your own free will.

Mahmoud Asgari, 16, and Ayaz Marhoni, 18, publicly hanged in Mashhad, Iran in 2005

By charging queer people with hudud — acts insulting the Prophet of Islam — totalitarian governments using Shariah law can put victims to death for having extra-marital sex or by calling consensual sex involving two people of the same gender “assault.” As The Advocate points out, “the photos might have stopped, but the killings haven’t.”

As of 2016, ISIS is still targeting and murdering queer people, uploading videos of their painful deaths to social media.

There Are Many Ideologies That Factor Into Government Sanctioned Queer Deaths

Construing the systemic acts of violence against queer people as solely the fault of Islamic extremism would be a mistake. For a decade, reports from Chechnya and Russia have shed light on the terrible fate suffered by queer people under the Kremlin. In April 2017, Nikki Haley, President Donald Trump’s Ambassador to the United Nations, spoke publicly of Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov rounding up queer men to imprison, torture, and murder as enemies of the state.

CNN recently interviewed an escaped Chechen refugee who had been detained, tortured, and had seen his friends murdered by the Chechen government. “They tied wires to my hands,” he told CNN anonymously, “and put metal clippers on my ears to electrocute me. They’ve got special equipment, which is very powerful. When they shock you, you jump high above the ground.” Though Chechnya houses a majority Muslim population, its government is backed by the Kremlin, which carries out anti-queer executions of its own.

Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev, left, meets with Chechen regional leader Ramzan Kadyrov.

Queer acts are not technically illegal under Russian law, but the Kremlin employs a loose definition of which acts demonstrate a threat to the nation. As GQ wrote in 2014:

The first [Russian] law banned gay “propaganda,” but it was written so as to leave the definition vague. It’s a mechanism of thought control, its target not so much gays as anybody the state declares gay; a virtual resurrection of Article 70 from the old Soviet system, forbidding “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda.” Then, as now, nobody knew exactly what “propaganda” was. The new law explicitly forbids any suggestion that queer love is equal to that of heterosexuals, but what constitutes such a suggestion? One man was charged for holding up a sign that said being gay is ok. Pride parades are out of the question, a pink triangle enough to get you arrested, if not beaten. A couple holding hands could be accused of propaganda if they do so where a minor might see them; the law, as framed, is all about protecting the children.

Again, it’s religious extremism of many sorts that endangers queer people around the world. Though the West now demonizes countries for keeping homosexual acts illegal, many such laws were put in place by European colonists. Amnesty International has pointed out that making homosexuality legal in African, Middle Eastern, and Asian countries is often the process of reversing homophobic laws put in place by European colonists centuries ago.

'Rolling Stone Uganda,' a tabloid paper unrelated to the American 'Rolling Stone,' celebrates the persecution of queer Ugandans in 2010.

As in the case of Uganda, homosexuality was first made illegal in 1533 by King Henry VIII. In Britain, it took until 1837 to abolish the law that decreed queer people could be stoned to death, but nearly 9,000 gay men were killed by the British government in the 1800s. Though it is no longer illegal in Uganda to be queer, if one is proven guilty of having had sex with someone of the same gender, that act carries a prison sentence.

But Surely Not in America, Right?

The United States government does not execute citizens for being queer, but as recently as 2010, American defense attorneys were still using the “gay panic defense.” The defense argues that a person can legally react with violence if a queer person gives them unwanted sexual attention, making it legal to kill someone for being gay — or even for being misconstrued as gay.

The “gay panic” or “trans panic” defense has often been used to explain the murder or assault of transgender people, particularly those who “pass” as cis-gendered and are victimized by their partners once they disclose their biological sex. As of 2013, only California has outlawed the gay panic defense.

Ofglen (Alexis Bledel) is debriefed on what the government has done to her.

It’s still just a science fiction program, though The Handmaid’s Tale will certainly introduce some viewers to horrors practiced around the world. What feels like a disturbing plot twist in Hulu’s newest show is, in many cases, just a hint at what actual people face every day.

New episodes of The Handmaid’s Tale premiere on Hulu every Wednesday.