Hey Kids, 'Shrek: The Musical' Is An Assault on Your Privilege

Rich kids in Malibu just don't get it.

Three years is a long time, but it’s not long enough to justify having seen 11 local showings of Shrek: The Musical. And yet, there I was entering the Malibu High School auditorium last week, ready to resume my dark habit of tearing children down for every last flat note and racially charged Eddie Murphy impression.

Malibu, of the Barbie Jeep variety, is notoriously posh, and the half-empty opening night audience reflected it. This theatrical work is so deeply rooted in class struggle, there is no way Malibu’s cast of horny pre-teens could compare to Morgan-Wixon’s 2016 production in Santa Monica, nor Boston University’s stirring adaptation in 2014, and it didn’t get anywhere near the New England regional theater production I saw five times in the spring of 2015. Children of this level of privilege — it occurs to me as I sit in a row alone, snapping pictures of strangers’ spawn after sneaking in without paying and stealing three cupcakes — could not possibly understand the ingrained politics.

Shrek: The Musical, it should be said, is not the same as Shrek, the animated 2001 feature. There are no significant musical numbers in the movie; instead, it’s simply an intentional — if lazy — attempt at postmodern subversion for children, delivering referential humor in forklift portions to an audience that may or may not totally get them.

The musical adaptation — which originally ran on Broadway in the late 2000s and starred the likes of Sutton Foster — takes a far more pure approach to the material, sucking the sarcasm from the plot and injecting it with a series of so-so numbers about fear (coincidentally, the definition of “shrek” in Yiddish) and love, in styles ranging from Broadway standards to Bon Jovi covers. The throughline of Shrek covering Smash Mouth covering the Monkees, at least, is consistent, the perfect summation of the multiple layers of media one has to tear through to arrive at the story of a Scottish ogre. Shrek: The Musical projects earnestness and heart in a way that’s embarrassing to watch.

I’ve changed since the last time I saw a local production of Shrek: The Musical. I got on some medication. I buttchugged a quart of apple juice immediately before being broken up with, resulting in a hideous crying jag out of both my face and my ass. I shared a bedroom with a total stranger and slept on a mattress on the floor and kicked out a Canadian squatter over the course of seven months. My weird eye twitch came back. I got a hamster. I got into a shouting argument with a hamster. I learned that my younger brother has very likely had more sexual partners than me. Life is a thrilling journey, even when you are ass-crying and slut-shaming a small rodent more than you are reading books.

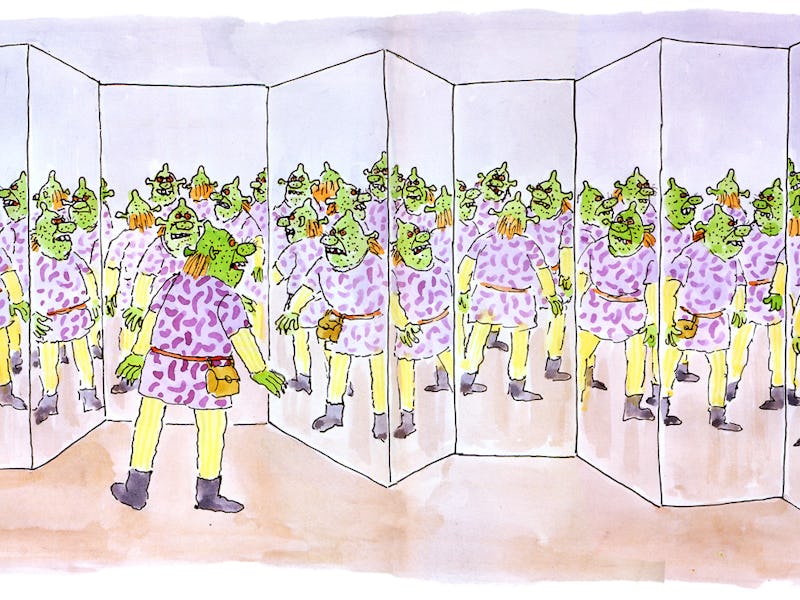

The reason I bring this up is because Shrek: The Musical, in spite of its ostensibly lazy movie tie-in premise, is a complicated work of art that holds a mirror to the person consuming it. And because this is a production of Shrek Jr., which is a shorter version of the musical, it means that there’s a full hour less to register every subtle comment on love, political unrest and body insecurity that it offers.

Malibu Middle School’s production is a strange one for many reasons, only some of which you can blame on the school. The actors will remain nameless, because I was afraid of asking for a program and calling attention to the fact that I had not paid the $15 (highway robbery) entrance fee and had an armful of frosted contraband. The namelessness will work in their favor because none of the performances were particularly good, and I am an authority on these things, as I performed the role of Principal Meyers in South Brockton Junior High’s February 2006 production of Who Stole Santa Claus?

Cast as Shrek is a young man who I believe will serve a brief tenure in a boy band before being unjustly admitted into an Ivy League school. The Fiona does the best with what she’s given, and the young woman playing Farquaad, complete on bended knee, is the member of the drama club that triggers me like a car crash — she has stacked the audience to guarantee an applause break at her every entrance, and speaks at the volume of a scream. She is half my age and I would still meet her at the flagpole at three o’clock. As for performances, Shrek Jr. is once again a letdown for the number of songs it cuts, including the overdone ballad-turned-politically prescient “Build a Wall,” sung by Shrek at the peak of the protagonist’s heartache.

Given the white privilege in the room, it occurs to me, as I start in on the green-candied popcorn I stole from under a nine-year-old volunteer’s nose during intermission, that the parable of Farquaad politiks will be lost upon its target audience entirely.

Yes, there’s a lot of good old feudalism on the surface, but at its core is a character that’s now more resonant then ever, presented without the sarcasm or bite of the film. Farquaad is a small man in all regards, in stature, in confidence, in spirit, in integrity, and his character is completely defined by his need to prove himself as a man in the traditional sense and as someone traditionally perceived as inadequate yielding power capably.

Then there’s the oppressed, postmodern fairy tale characters trying to rise out of the swamp (whoa) and claim their place in society as equal citizens, refusing to be further disregarded, via song and dance numbers like “Freak Flag.” And our protagonist is someone who’s uncomfortable in his own body but learns he’s part of a community larger than himself and helps in toppling over his tiny but powerful overlord, finding traditional love and “releasing” his beloved from the trappings of her own insecurities in the process. It’s not a perfect parable, but it’s a pretty stunning one to see today.

This cast’s struggles are more aligned with the Farquaads of the world than the Gingerbread Men (oh my God Jamie). What results is an underwhelming performance that gives one a feeling of existential dread; that’s me speaking as an experienced viewer who drove an hour without a driver’s license and was certainly not invited to attend, much less review the performance. In fact, had they known my intention, I would have been asked to leave, at best, and be stripped of my 401K and IUD at worst.

These thoughts occur to me as I eat my final cupcake whole before the little girl I stole it from succeeds in making eye contact with me, which is just before the cast launches into its final chorus of “I’m a Believer.” Yes, they can coast on mediocrity for the rest of their lives. Yes, they are worth more money than me, my family, and the state of Rhode Island combined. Yes, they could hit me with their car and get away with it. I welcome it, for I have the sweet taste of something they don’t understand: the undertones of Shrek: The Musical and also a broader view of the human experience … and also bleeding gums I can’t afford to fix. And that taste, dear readers, is about as sweet as a Malibu mom’s dry ogre cupcake.

But what do I know? I’m just the most qualified Shrek: The Musical critic of all time.