'The Walking Dead' Revels in the Process of Elimination

At this point, death is the show's chief narrative device. Expect the last season to be, at minimum, eye-opening.

The seventh-season premiere of The Walking Dead, “The Day Will Come When You Won’t Be,” is distractingly brutal, but the most striking thing about the episode is that it represents an almost absurd exercise in plot decompression. The show’s directors never met a scene they couldn’t stretch out like a disembowelment, but this reluctance to move on has never been so obvious. We now have enough material for maybe one 7-minute segment of an episode (bookended by commercial breaks) occupying an entire hour. It’s agony to watch, but born of boredom, not any emotional connection to the characters.

Granted, it makes the plot easy to summarize. To teach Rick and the group a lesson, Negan kills Abraham. Then, to further teach them a lesson, he kills Glenn. Then, to teach Rick yet another lesson, Negan takes him on a zombie-dodging ax-fetching errand. Then, to teach Rick and the survivors yet another goddamn lesson, he pulls a binding of Isaac bluff lifted from the Book of Isaiah and acts as though he’ll force Rick to cut off Carl’s arm to save everyone else’s lives. Finally, everyone drives off.

It’s a paragraph of plot.

On a meta level, The Walking Dead performs a dance with its audience that’s far more interesting than the series itself. I have to wonder: Was last season’s block of episodes which endlessly toyed with the possibility of Glenn being dead set up solely to make viewers think he would be safe? After all, they wouldnt go through such an elaborate, frustrating fake-out just to kill him off now, right? Yeah, they would. So there.

His head got tenderized and social media went wild. Editors cried havoc and released the thinkpieces of war.

Whatever you think of the characters, this turn is narratively questionable, undermining the authority of plotting by forcing the audience to consider out-of-world motives. But a good story isnt the point. The Walking Dead, like other popular serialized shows, works on an addiction model, and big moments like these are what string people along. They create huge social media buzz, turning each episode into an “event.” When the show is on a streaming site, these are the beats which cause viewers to look up from their laptops or work or kids and take notice, which is enough to get them to continue bingeing what they may otherwise shrug off. Any connection to the characters is mostly theoretical and based on how long they’ve been a regular.

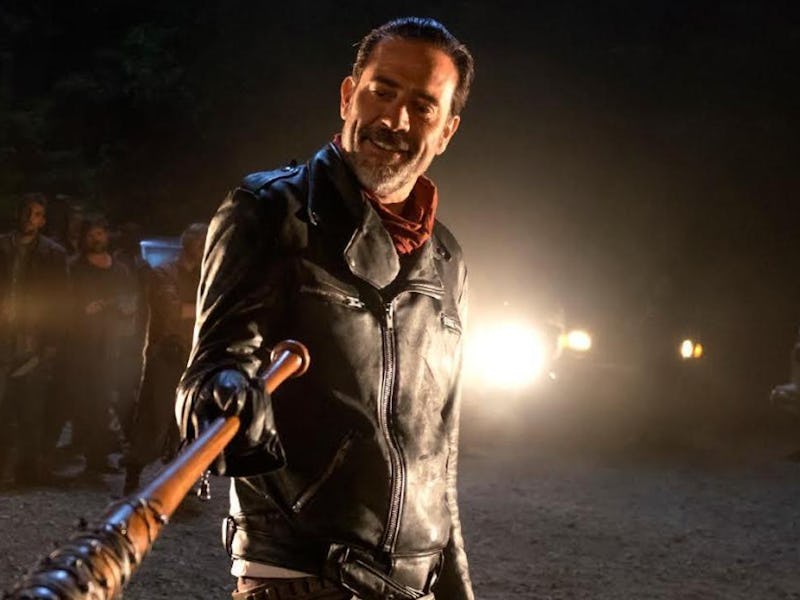

“The Day Will Come When You Won’t Be” is for the most part a two-hander between Rick and Negan, with the former doing little besides look shellshocked and the latter extending the schtick he established in the interminable final 10 minutes of the season six finale. Seriously, you could lose 10 minutes from this episode just by trimming Negan’s extraneous chatter. Letting Jeffrey Dean Morgan cut loose with a truly despicable character is an exciting prospect, but he can’t do much more than mug his way through some rough material. The series, trapped as it is in a cycle of “maybe things will turn out okay” / “everyone will die” desperately needs this man to represent an unparalleled existential threat. But really, after countless roving bands, a more somber rival warlord, a cannibal community, a fascist hospital, and the thousands of zombies, does a man who makes bad jokes and swings a baseball bat with a nickname really bring anything new to the table?

As for permanently dead Glenn, he was a nice guy who we know loved his wife and friends and was never fleshed out more than that as a character. He was symbolic as a consistent, positive Asian presence on American TV, but his significance within the world of the show was up for question.

Of course, springing a twofer of “important deaths” was a reasonably clever way for the show to upend the expectations that had been built over the course of this summer, a less-anticipated answer to the “Who’s gonna die?” theorizing. When viewers think the question has been answered, they let out their breath only for things to abruptly take a turn for the even worse. And of course, the speed with which Abraham’s death leads to Glenn’s lends the second mortality more impact, making an even stronger argument that it would behoove The Walking Dead to move at a faster clip.

Indeed, the smaller action beats of this episode are where it becomes watchable. Rick leaping onto a hanging zombie to escape gunfire and then dangling over a grasping mass of them is good suspense — even if it is muted by using Negan as a savior not once but twice — and by the overall pointlessness of the sequence.

Finally there is this: The show tries to go for the emotional jugular while also reveling in base violence. That’s troubling inconsistent. Drawn-out scenes of people mourning set to sad music start to feel more like a gesture toward meaning than the real thing. Do people watch this show for the characters? Yes, but only a few of them. Daryl and Michonne get to be cool as the rest die in creatively bloody, exquisitely FX’d ways. There are a lot of expendables.

Six seasons in, the show is ramping up the bloodletting to stay relevant. It’s fascinating to watch as a TV viewer because there is the sense that we’ll finally find out who the show was about, if anyone. Death is good like that.