I Mummified a Hot Dog and Now Understand the Human Body

A controlled environment is the key to preventing decomposition.

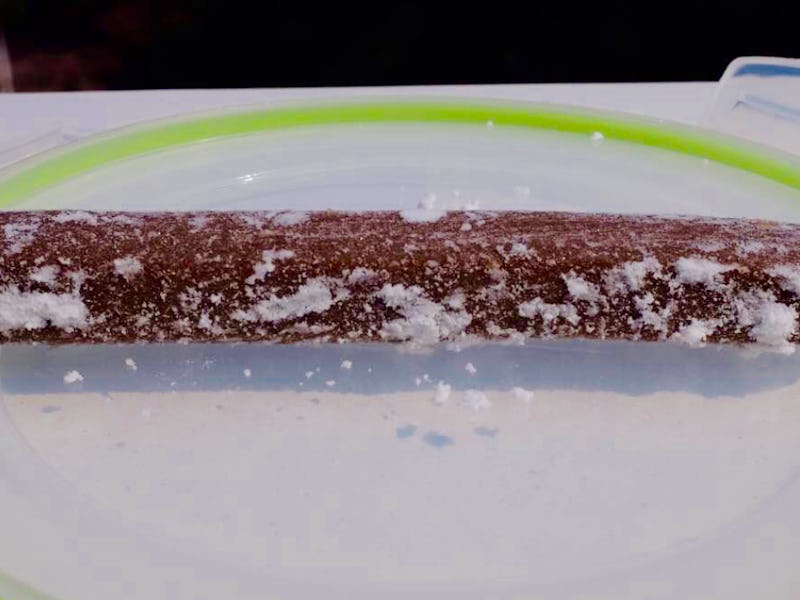

I have had a hot dog under my bed for the last two weeks. Trapped in clear Tupperware and buried in baking soda, it no longer resembles something that you throw on a grill and serve to friends slathered in mustard. It sort of looks like a cigar or maybe part of a branch, if those things smelled like hot garbage.

My hot dog has come to look like this because I’ve been trying to mummify it. With directions courtesy of a science experiment I found on the site Science Buddies I went from having a Krasdale dog to something that you might be tempted to leave in the mailbox of someone you hate.

And you, too, can mummify a hot dog this heat-domed summer. All you need is a hot dog, baking powder, and an airtight storage box. Science Buddies recommends conducting the experiment anywhere from two to four weeks — I’m at week two and while the hot dog has turned dark and strange, I’m sure it would get darker and stranger if I keep it around. Citizen scientists are encouraged to observe the hot dog.

Spread a layer of baking soda in the box, nestle a hot dog flat within the baking soda dunes, and cover the whole thing up with at least an inch of baking soda.

Now, you engage in that most important step of mummification: waiting, waiting, waiting.

After about a week, check out the hot dog; while you’re at it, dump on a fresh coat of baking soda. Then — you guessed it — wait about a week more. After the second week is over, it’s worth taking a careful sniff and glance at your mummifying hot dog. Most probably, your hot dog has now become stinky and not at all drool-worthy, going from this:

Mmm, hot dog.

To this:

Do not eat.

I called Ronald Wade, director of the Anatomical Service Division at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, to talk about mummification and what happened to my hot dog. The University of Maryland is home to the Burns Collection, an assortment of 200 medical mummies that were assembled in Scotland and acquired by the school in 1820. Bodies embalmed in chemicals and cured in sugar and salt, some of the “medical mummies” are now used by the school’s medical students as teaching tools.

“Mummies are deceased bodies that may or may not have been purposefully preserved,” says Wade. “When we look at the mummy itself, you can look at the physiology and the anatomy, but you can also look at the contents of the stomach, the debris that maybe bacteria and aging has complicated. For example, we can see that most of the Egyptians didn’t live much past 40 and most of them had very bad tooth decay, because a lot of the flour had ground sand it in and it wore down the enamel of their teeth.”

Wade explains that there are mummies that were intentionally preserved for religious reasons, like the mummies of Egypt or the Chinchorro mummies of Chile, and then mummies that were preserved because of precise environmental reasons.

“Where there was no process and the bodies were, say, placed in hot, dry sand or placed in bogs where there was no oxygen, they would mummify,” says Wade. “Or up in the Andes, and even in Chinese mountains, these places would have cold, dry, air and basically kind of freeze dry the body. These are environmental situations where there was maybe a lack of oxygen, which inhibited bacteria, and the breakdown and putrefaction of the body.”

When I told Wade that my hot dog was now dark, he said that makes sense — that’s a part of the desiccation, when moisture is removed. It’s not real mummification (let’s face it, hot dogs are hardly “natural”), but it’s a damn good imitation. “The only problem with using a hot dog is that there’s already a lot of preservatives — all those nitrates,” Wade advised.