Fuck the Faux-Happiness Economy

Researcher Will Davies thinks Aldous Huxley's prophecies are coming true.

For most of human history, happiness was a personal or familial matter. But new technology changed that for good — although not necessarily for the better. The rise of social media, sentiment analysis, artificial intelligence, and biometrics have turned happiness into its own metric — one that obsesses over nations, businesses, marketers. And then there’s Will Davies, who does not approve of this new faux-happiness economy. A senior lecturer at the University of London, Davies is the author of The Happiness Industry: How the Government and Big Business Sold Us Well-Being, a critical history of efforts to quantify and manipulate happiness, which reads a bit like a call to arms.

What concerns Davies is the historical anomaly of engineered happiness, and the reason it concerns him is that it’s disingenuous: an attempt to leverage conviviality and positivity into productivity. Davies was, for instance, fascinated when, a couple years ago, someone leaked the managerial instructions for the Pret A Manger sandwich chain. The notes included a weird bit of guidance: Staffers were told that they should be regularly touching each other.

“Not in a creepy way,” Davies says. “Well, it is kind of creepy. But, they should be, you know, smacking each other on the back, and they should give out a certain number of free coffees every day.”

This sounds a bit bizarre — and Davies reiterates that it is — but businesses and governments can make pretty strong arguments that quantifying, and maybe even engineering, happiness can work. Bhutan, for example, monitors Gross National Happiness, though this concept seems more upstanding than the current trends.

“It’s quite clear that happiness is now a sort of currency in its own right,” Davies explains. Inverse spoke with him about the projected value of this new currency.

Will Davies

How do you define happiness?

It’s useful to remember that the word has a common root with the word ‘happenstance.’ Historically, it’s linked to the idea of something that just happens. It’s not something you deliberately try to engineer. Most efforts to produce more happiness are self-defeating, because you end up focusing on what you’re trying to get out of things — rather than just focusing on the practices and activities themselves.

That seems at odds with the ongoing cultural moment. How do you think most people think of happiness?

Over the last 20 years or so, there’s been a whole set of expertise, business practices, and medical practices that have paid more and more attention to how positive emotion can be triggered. They’ve found various things that often produce positive emotion: being near greenery, going for a run, giving to charity, spending some time with your family. All of these things are good things. I do them myself and I recognize that they make me happy. But what has happened is that we’ve started to see happiness as almost a medical outcome.

In the business world, there are efforts to try and keep employees at a particular level of positivity the whole time, because it’s a way of also keeping them more productive — working harder and working longer. This can often result in some rather cynical management practices and also some cynical marketing practices, which try to artificially engineer a culture of positivity and happiness.

Do you think the actual effect is unhappiness?

I recently rang up my local government in London to request some service. After I finished the phone call, I got a text message from the counsel asking me not if I was happy with the service, but how happy the employee seemed to be serving me.

It can make it harder to talk about negative feelings and unhappiness if they’re not seen as acceptable. In workplaces, I think it also creates a certain sense of irony and of detachment, where you’re kind of performing a level of happiness as a part of your job.

The ancient Greeks had a different concept: eudaimonia. If someone’s very crudely translating the term, they’d call it ‘happiness.’ But to the Greeks, it was more than that: it was about human flourishing, thriving.

And how you live.

Yes. And they wanted us to fulfill our functions as humans, but their definition of human function would not resemble ours today.

There is still a tradition of philosophers, and even economists, who are interested in this. My book is mainly a critical book. I tell the history starting with Jeremy Bentham. There’s eudaimonia but there’s also hedonia, which is about pleasure as opposed to flourishing. Bentham’s often seen as a hedonic philosopher.

Bentham thought happiness was almost like a physical symptom, a bit like blood pressure: something that happens in the body or in the brain, and changes the way you feel in a relatively unremarkable scientific sense. To him, happiness was not a philosophically complicated thing: We have these sensations in our bodies and in our brains, and we pursue the good ones and avoid the bad ones. It’s as simple as that. He didn’t have any sense, like Aristotle did, that this was about learning how to live well.

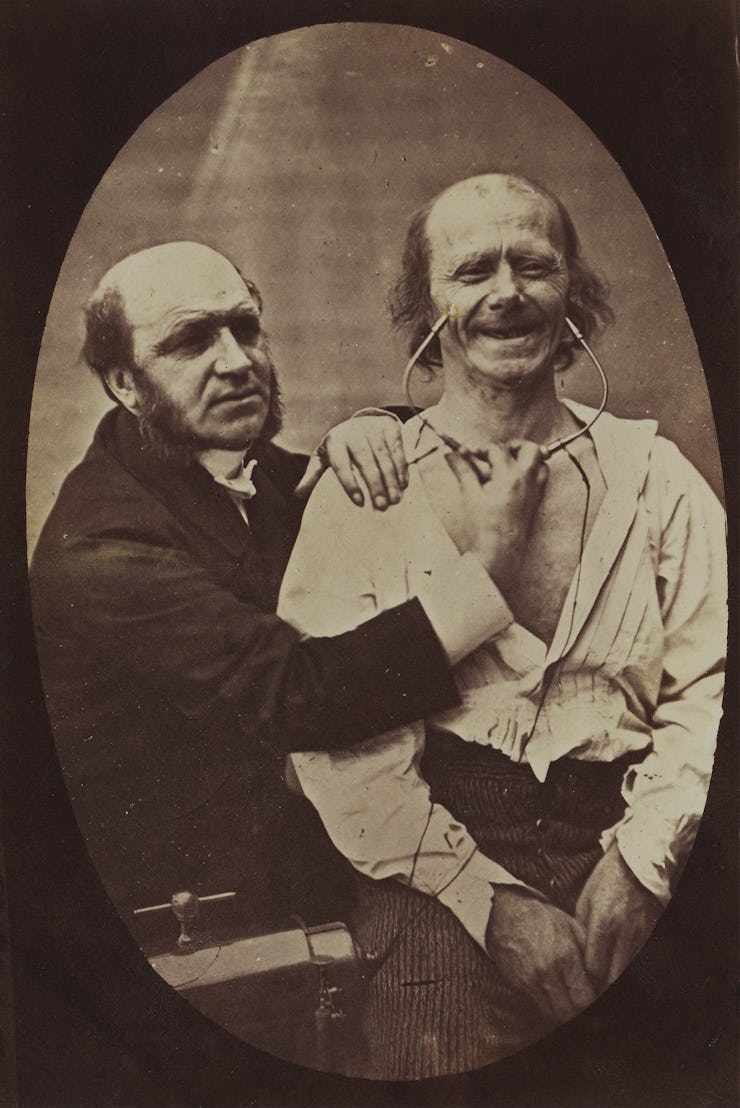

For Bentham, if someone were to stick a wire into your brain that pumped you full of good feelings, then that was an equally good way of delivering a good life as giving to charity or going for a jog. These things are all equivalent if they deliver the same quantity of happiness. That’s where you get Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World dystopia. I wouldn’t go as far as to say that’s what we’re living that out, but I think you can see aspects of Bentham’s ideology around us.

How do our concepts around happiness determine — or limit — our lifestyles?

In Britain, there are some quite manipulative uses of positive psychology in the area of welfare and benefits. Britain has more of a social safety net than the United States, so this sort of stuff potentially penetrates more into people’s lives. But, if you’re currently claiming unemployment benefits in Britain, you are now made to go to various positive thinking programs in an effort to try and make you more employable. You might be someone who actually suffers with serious mental or physical health problems, or have other reasons why you’re not really able to look very hard for work — because you’ve got other things that you’re worrying about. And yet, people are being made to take part in these ritualized positive thinking projects, where they have to stand up and recite certain affirmations: ‘I can achieve anything’ and that sort of stuff. That’s quite manipulative.

A more American example would be the ‘You can be a millionaire, if only you’d believe it’ cult. A lot of people have already criticized the new-age, cult-like aspects with some of this stuff.

I think we do live in a society where we’re encouraged to see positivity as a way of advancing our own prospects in life. If you’re not being upbeat and you’re not believing in yourself, you can’t really expect anything to work out for you. Therefore, you have to treat your happiness as a sort of resource: You need to maintain it, invest in it, sustain it. You have to think about what the social, cultural, and political effects are of living in a society where people are treating their emotions as a form of capital — something they’re investing in so as to get some kind of return.

Would you agree that general unhappiness, or even depression, is pervasive today?

Yes. This is not to be denied. Obviously, it’s difficult to say exactly where you draw the line. At any one time, in Europe and the United States, the number of people who have diagnosed depression isn’t that high. It’s at around seven percent of society — something like that. But people are much more aware, across the board, of moods and mood disorders and depression as things that can afflict them at any time. There’s been a cultural turn towards medicalization.

Students now come to me describing their angst in medicalized terminology. I was in university 20 years ago. I think back to my behavior: I went through depressive periods, but I don’t think I ever really framed it as Depression, with a capital D. I just thought, sort of, life sucks.

You write a bit about how technology can be used to monitor happiness. How effective is this stuff?

The real frontier is social media monitoring. It’s often called sentiment analysis, where you can try and detect someone’s mood via their behavior on a social media platform. Facebook carried out a very controversial experiment, called an emotional contagion experiment, where they deliberately tweaked the news feeds of 700,000 users to see if they could change the way they behaved online. The idea is that if you see a lot of happy stuff in your feed, wouldn’t you also put more happy stuff up? They discovered that they could do this.

That’s sentiment analysis. Teaching computers how to interpret the emotion in a given sentence. But there’s also a wider field called affective computing. There’s a whole affective computing lab at MIT, where a lot of these new technologies and companies and startups that do it have spun out of. This is more things like facial scanning and facial recognition, tracking the movement of people’s eyes, and trying to sense how happy someone is via their body in various ways. It might be a combination of their facial movements, their sweat, their heart rate — all these indicators. If you combine that with sentiment analysis — ‘What kind of information are they putting into Google? What are they writing on Twitter?’ — the people doing this reckon they can get a pretty good sense of how someone’s feeling. One of the most famous companies doing it at the moment is called Affectiva.

If I decide that you’re right – and capitalism is now a misguided happiness machine – what should I do to remain sane?

There are political and privacy battles being fought. The Facebook experiment resulted in a big backlash, so that’s one of the frontiers. I would say, rather than abandon the whole argument about happiness, what’s needed is a different happiness agenda, one that focuses on collective institutions, and one that tries to make the argument that a great deal of human misery could be alleviated politically rather than through different behaviors and different medications and different products. You can’t just fight happiness with misery. That’s not the way to go. It’s sometimes tempting, when you’re obliged to smile all the time, to just frown.

We all need to use social media less; that’s pretty clear to me. I use it a lot, but I don’t think that it’s good for us in terms of happiness, and I think the dawn of smartphones has been very, very problematic. It’s not easy to get away from this web of monitoring, and operating in this increasingly emotionally smart environment.

You can’t just turn the clock back. I don’t want to make the Luddite argument, but I think that ultimately we need to cling onto the authority of human voice, and say that human beings, while they may not know how they feel, still need to express how they feel. What’s empowering about even failed social movements, like Occupy, is that they show people that, sometimes, they can stand up and say what’s in their head. And they can say it out loud, in public. This whole apparatus that I’m describing, and that Bentham was imagining, rests on the idea that you don’t need to ask people how they’re feeling, because you can just detect it. That’s really what I’m against.

Verso Books just released The Happiness Industry in paperback. It’s available here.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.