Does Anyone Care About a Sequel, 20 Years Too Late?

If it's been a long time since the last movie, does the sequel always fail? What about when it succeeds?

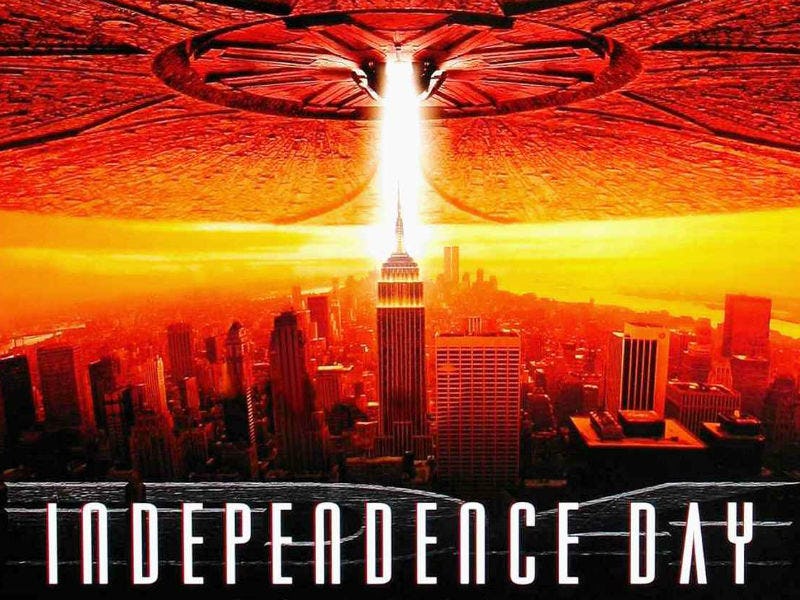

Much like a ginormous alien mothership being forced to tuck-tail and leave our planet, the box office results for Independence Day: Resurgence seem to reflect a tepid feeling from the general moviegoing population. And though its $41.2 million domestic box office (and $143 million worldwide) is nothing to scoff at, this amount was short of the $50 million that this 20-years-later sequel was expected to earn. The original Independence Day made $871.4 million worldwide back in 1996, and though it’s possible the new sequel could make up some ground during its full theatrical run, that seems pretty unlikely. The 20- year gap between the original Independence Day and Resurgence seems an easy factor to blame here, but what is the success rate of sequels with similar gaps after the original? Here’s a snapshot of this odd movie phenomenon.

Remakes are sort of off the table here, only because the very nature of a remake has a new built-in hype (or built-in backlash) embedded into the perception of the installment to begin with. Analyzing how the Brendan Fraser version of The Mummy performed financially and critically in contrast with the Boris Karloff original is sort of meaningless – or, at the very least, a totally different phenomenon. It’s safe to say audiences approach sequels with a different set of expectations than remakes or reboots. (Though there is an imminent exception coming our way really soon.)

If we look at movies with 17 years or more between the original and the sequel, the numbers tell a fairly inconsistent story. The easiest place to start is obviously with the Star Wars films. If we consider The Force Awakens (2015) as the direct sequel to Return of the Jedi (1983), we are looking at a 32-year gap. The Force Awakens made over $2 billion, while Jedi made 572 million (adjusted for inflation.) Here, the argument could be made that a giant gap between sequels was a positive thing, considering Return of the Jedi garnered mostly negative-to-lukewarm reviews (this NYT review from 1983 is particularly scathing) and is the most poorly regarded of the classic films. But, there’s a flaw in this analysis: there were three other Star Wars movies released in-between ROTJ and TFA, and they all did better at the box office than ROTJ. In fact, if you look at the The New York Times review of The Phantom Menace in 1999, it’s surprisingly full of praise, even the phrase “up to snuff” is used, which, as anyone knows, is certainly not something anyone would say now.

I like calling this anomaly “hype-hangover.” We all know Return of the Jedi is a better movie than The Phantom Menace, but in 1983, maybe everyone was sick of Star Wars while in 1999, people were ready to love it. Point is: there was no box-office backlash against The Phantom Menace ($1.2 Billion), and the 16-year gap between it and Return of the Jedi was probably a benefit. It didn’t hurt that a whole new generation of Star Wars geeks had been born in the interim.

In terms of our larger analysis of big time gaps between sequels, Star Wars stuff represents a some kind of relationship between money and years, but no real causation. Star Wars as a whole is seemingly a money-making world unto itself and probably plays by its own set of indiscernible rules.

What about Indiana Jones? There was 19 years between The Last Crusade and Kingdom of the Crystal Skull. Here, we’re nearly in Independence Day territory since the gap between these Indy movies is almost two decades. Adjusted for inflation, The Last Crusade made $474.2 million in 1989, while Kingdom of the Crystal Skull made $786.6 million. Seems crazy, but the gap between these two films almost certainly – maybe without a doubt – helped Kingdom of the Crystal Skull’s box office performance. Because there is NO WAY anyone in the right mind thinks it’s just a way better movie than The Last Crusade. I don’t even need to bother telling you this, but the aggregate audience score for The Last Crusade is 92% and The Kingdom of the Crystal Skull is 54%.

But Indiana Jones is an ultra-beloved character, so the gap between his appearance in 1989 and 2008 seems to be a benefit because the character (as played by Harrison Ford) was the main draw. Theres every reason to believe an Indy movie in 1999 would have done well, too. Maybe not Phantom Menace money, but, possibly better than The Last Crusade. With a fictional person like Indiana Jones, absence definitely make the heart – and collective nostalgia – grow fonder, and that seems to translate into dollars. (Actually, this might just be a Harrison Ford, specific thing. Are we ready for an Air Force One Part 2: Nostalgia One a Plane, yet? How about The Mosquito Coast: Reloaded?).

In contrast, the characters of Independence Day are NOT as well-established or beloved as Indiana Jones. There’s no need for an analogy here, because comparing the characters of Independence Day to the characters of Indiana Jones is like comparing the characters of Independence Day to Indiana Jones. If you’ve seen Independence Day: Resurgence then you know what I mean: remember President Whitmore and his daughter? They’re your favorites, right?

But what about characters people objectively DO love? What about Dorothy and her gang from The Wizard of Oz? There was 45 years between the original Wizard of Oz and its sequel, Return to Oz. When adjusted for inflation, the original film, made about $247 million. (Plus, let’s be honest, the amount of times people have seen it on TV seems incalculable.) In contrast, Return to Oz made only $25 million, adjusted for inflation. Like the Indiana Jones critical gap, it’s easy to guess what the critical consensus of Return of Oz is as apposed to The Wizard of Oz. Sure, it might be fashionable to claim Return to Oz is a cult classic in the 2016 climate of rescuing trashy movies from cultural obscurity, but no one is going to pretend like it’s actually better than the original, nor could you really construct an argument that it should have made more money.

This isn’t to say the original Independence Day is directly analogous with The Wizard of Oz and it’s pointless sequels (the less said about Oz the Great and Powerful, the better) but, in terms of a model which matches, this is the closest comparison that works: the original movie is well-liked and does very well at the box office and then, a sequel over 20 years later, does shitty and everyone hates it.

And even if you don’t buy Independence Day and its bizarrely late sequel as being analogous to Oz-stuff, then how about The Blues Brothers and its awful sequel Blues Brothers 2000? The original Blues Brothers is a comedy classic which pulled in $115 million in today’s money, while the exactly twenty-years-later sequel - Blues Brothers 2000 - only made $14 million. Robert Ebert gave the latter two stars and claimed it would have been better if the “story had been left out” in favor of a bunch of good music.

Maybe the true rubric here is some kind of mix of the legit quality of a movie combined with an absence of the franchise for a big chunk of time. When enough time passes, an original film (or most recent sequel, or franchise as whole) can gain a different kind of status than it had when it was “new.”

Perhaps the best — or most recent — example here is Mad Max. If we adjust the global box office totals for all three original Mad Max films for inflation, the original 1979 film made $388 million, its “sequel” The Road Warrior(1982) made $57 million, and Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome(1985) earned $82 million. A full 29 years later we get 2015’s Mad Max: Fury Road which is kind of a sequel to the original storyline, but not a reboot or a remake.

The original films have a mixed critical heritage and basically did okay at the box office, but beyond the first one, were not (like Independence Day) solid money makers. But then, all the sudden in 2015, Fury Road made over $400 million and received almost completely positive reviews. In fact, it’s sitting at 97% on Rotten Tomatoes.

No one really saw this coming, mostly because those original Mad Max films were such a mixed-bag culturally speaking and weren’t awesome moneymakers, either. Meanwhile, Independence Day is something a classic of late-90’s popcorn movies. Now, it looks like its sequel is on the road to being quickly forgotten. Meanwhile, neglected franchises of the past (like Mad Max) suddenly have the ability to dominate not only the box office, but in critical circles, too.

What does all this mean? While not technically a sequel, the impending release of the new Ghostbusters is dealing with a similar time-gap; it’s been 27 years since Ghostbusters II. Like Indiana Jones, Ghostbusters seems to be super-beloved franchise, and its original stars are returning for cameos. Will the brand-loyalty of the fans help Ghostbusters at the box office, regardless of it’s objective “goodness” or “badness?” If it is poorly reviewed, will that matter? Ghosbusters feels like a safe bet, but maybe the safe bets of Hollywood’s past are really its future failures. Meanwhile, the underdog franchises that time forgot might just be tomorrow’s biggest hits.