Noah Baumbach on the Weird Beauty of Brian DePalma's Vision

The two filmmakers talk to Inverse about turning their friendship with Brian De Palma into a career retrospective documentary.

Filmmaker Brian De Palma was always the most underrated member of the New Hollywood movie brats. As his friends and fellow directors Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, Francis Ford Coppola, and Martin Scorsese were defining popcorn blockbusters like Jaws and Star Wars or serious-minded award winners like The Godfather and Taxi Driver, De Palma embraced a more tawdry side of filmmaking.

Through Hitchcockian thrillers such as Sisters, Dressed to Kill, and Blow Out, De Palma was lauded by king-making critics like Pauline Kael and J. Hoberman. He always managed to do things his own way whether he made a classic or a box office bomb. From low budget experiments like Dionysus in ‘69 or Home Movies to big studio hits like Scarface and Mission: Impossible, De Palma remains an American jack of all trades. And though he’s been in the public eye for four decades, he still remains a bit of a mystery.

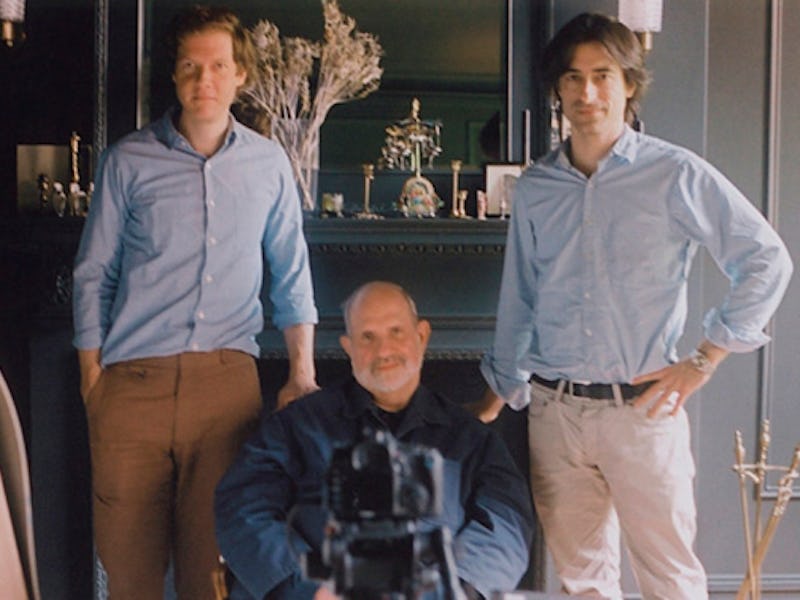

His idiosyncratic career has inspired filmmakers Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow, who have long been both his friends and admirers. A few years ago, they asked the cinematic elder statesman if they could take their dinnertime chats and turn them into a retrospective documentary about his wild life and career. The result is De Palma, Baumbach and Paltrow’s quasi-autobiographical trip through De Palma’s filmography simply and candidly explained by the filmmaker himself, that hits theaters on Friday from production company powerhouse A24.

Inverse sat down with Baumbach and Paltrow to talk about their process, De Palma’s level of enthusiasm about making a documentary about himself, and how the process differed from their regular filmmaking experience.

What was the first Brian De Palma movie you ever saw?

Jake Paltrow: We both saw the same one.

Noah Baumbach: I heard about a lot of them before I saw them, but Body Double was the first one I saw in the theater. I went with friends, but ran into my mother who was seeing it separately. I wasn’t quite old enough to see R-rated movies, but I was doing it anyway.

You both eventually became friends with De Palma. Why did you want to turn your friendship into a career retrospective documentary?

JP: We’d spent so much time with him that we recognized he was willing to talk on camera the way he talks to us in his sort of very honest, unguarded way. It was a great thing to archive, initially selfishly for us, and then when we started realizing this could be movie material.

The film's theatrical poster.

What was your line of questioning like? Did you simply want to go chronologically to see what he could recollect, or did you want to pick out particular moments to make sure he talked about those?

NB: It was a little bit of both. Generally we really were going in order, movie to movie. But the conversations would often end up jumping decades to another movie because it was relevant to what he was talking about at that time. It had a kind of freewheeling, open trajectory.

You guys don’t appear in the movie, and there’s no talking head commentary by others. De Palma basically tells his own story like a filmed autobiography interspersed with clips. Was that always want the format?”

NB: We knew we were very much a part of it regardless because we are talking to him and he’s talking in a way that he talks to us. So we were a way to get him there, and then we took ourselves out afterward. We had had that idea from the beginning. We didn’t want it to feel like an interview. We wanted it to feel like a story.

Was he open to the idea of the documentary when you first approached him and did he enjoy the process?

JP: He was, to a point where I vividly remember how electric he was when we turned the camera on. His ideas were so clear. The things he said were concise but alive.

NB: He took it very seriously. He understood what it could be and what it should be, so it wasn’t like we had to cajole him. He was really up for it from the beginning, and we talked all day. You can hear that his voice gets raspy at certain times because those were late in the day conversations. And then he’d come back the next day and he’d wear the same outfit and we’d go again for about a week.

Why do you think he was so invested in telling his own story?

JP: I think it’s as simple as we’d spent so much time with him and that we asked. I don’t think Brian had any sort of inner desire to do this. My hunch is that he probably wouldn’t have done it with somebody else. When he said yes, we put it together very, very quickly. I think within a week we were probably shooting it because it was like, what if he changes his mind?

It was interesting to see De Palma be openly candid about himself. When he talks about the ups and downs of his career he says “We don’t plan them out.” Why do you think he’s so divisive in general, perhaps unlike any other filmmaker?

NB: He has a strong point of view, one of the strongest in the history of movies, and I think that’s noticeable. Just that quality alone — it attracts critique because it’s not the way it’s normally done.

Is there any movie of his that you’ve come to see in a different light, or discover in a different way through making the film?

NB: When I saw Carlito’s Way in theater I didn’t appreciate it as much as I do now. I think we both feel that way. Brian says in the movie that he watched it after it had already come out and it hadn’t done as well as he’d hoped, and he was like, “I can’t make a better movie than this.” I know exactly what he means. That movie is, I think, brilliant filmmaking. It’s done by somebody who has harnessed everything he knows how to do.

Are there any stories that he told you that come to mind that you had to cut out?

JK: You sort of have to forget that stuff.

NB: We weren’t cutting it the same way as a narrative film. The editing is the directing in a movie like this. The more you work on it and watch it, what should be included becomes clearer and clearer. I could watch two hours of Brian talking about Dressed to Kill, but I think we really had a feel of the rhythm of this particular movie. We weren’t thinking about outtakes and just felt like stuff that wasn’t going to hold could go.

There’s at least two more good stories about how Cliff Robertson was an asshole, though.

Are there any other filmmakers that you could see yourself doing a similar documentary about?

JP: They’d have to become our friends first, probably. I think that’s part of the thing that makes this work is that you’re just transposing the thing you normally do onto film.

NB: But other filmmakers that we’re friends with don’t live down the block. That’s the thing, we all live within a four-block radius. That makes it easier to meet for dinner and to do the documentary.

There are filmmakers who I admire and I’m also, as is Jake, close to, but I think it’s also they have to be equally up for it and want to kind of put in the time.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity. De Palma opens in theaters on June 10.