The Mob Museum in Las Vegas Is a Moment of Silence Amid Lights and Sounds

The monument to organized crime is a colorful and loud eulogy to the era's countless victims.

When you write about superheroes for a living, as I do, you tend to think a lot about power. The best comics have always taught great power needing great responsibility to make the world better, or at least less of a pain in the ass. But reality has never lived up to that ideal. Comic book ubiquity rose and fell alongside America’s storied mob history, wherein people were used and wasted like cattle. The human costs of crime always overshadowed the glory, for me, even as I grew up in New Jersey, where my teachers and town police loved The Sopranos.

But on a recent trip to Las Vegas — itself a living monument to the lasting influence of organized crime — I found myself gravitating to the downtown Mob Museum. If the ghosts of gangsters and gamblers haunted the casinos (and surrounding unmarked desert roads), I felt it right to exorcise them at their mausoleum.

Sheltered from Nevada’s dry winter air, I wandered the halls of the city’s preserved post office that now houses this sleek, modern museum. The exhibits channel enough corny pop imagery to give off an overall dad-jeans vibe, but they have educational integrity, too. To my pleasant surprise, the museum is conscious to address not just the bloodshed that forged America’s urban empires, but also whose blood had been spilled.

It all feels right, until you’re getting ready to leave.

By the nature of mob history, of course, you don’t get to know everybody whose lives ended at a Thompson barrel. Comprehensive records don’t exist that could personalize victims; the Holocaust Museum in D.C., for one, benefits from the fastidious record-keeping of the Third Reich. Mob history is by no means strictly about the people who died, but also the people who lived and fought the era, and that feels like this place’s purpose. This isn’t a memorial, but a warning: This is what happens when people are desperate and do desperate things.

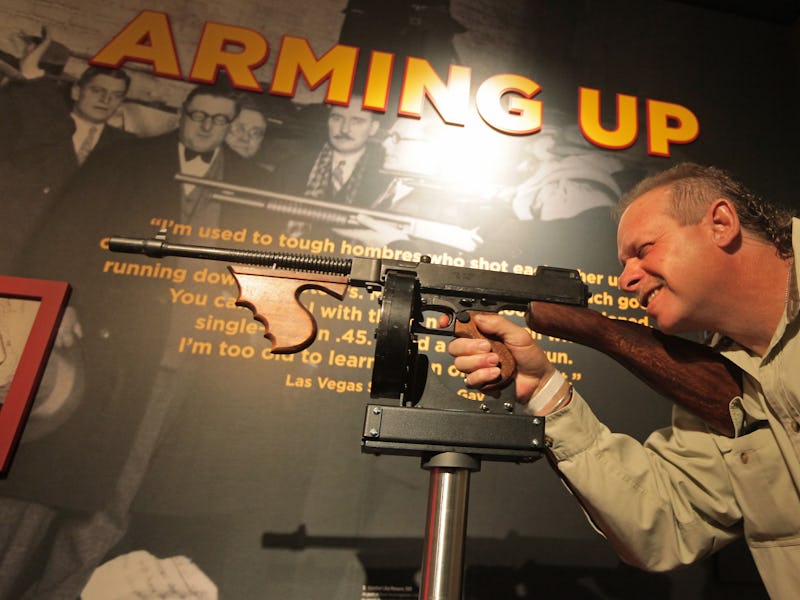

The bodies that kept mob trains chugging have a monolithic presence that overwhelms throughout the exhibit. On floors that take you inside the structure of mob hierarchy and operations, you can’t help but place yourself in the time and place. A few displays show the preferred tools of hit men, exhibited under fluorescent lights and over vibrant red velvet. You easily picture being at the receiving end of that glass candlestick or icepick.

Prostitution’s structure is also on display. These women owed so much to madams and rent every day and every week and every month; it was straight up slavery. Duh, you’re thinking, but this is the stuff that gets glossed over. The Mob Museum presents this in first-person mode.

The museum doesn’t shy from corniness, given its appeal to tourists who proudly have Casino and Goodfellas on DVD. Occasionally, there are timed video presentations that explain bigger events with black-and-white footage, History Channel-style interviews, vibrant jazz, and so many machine-gun sound effects you’ll be grateful for the peace and quiet in the restrooms. But the production budget is put to good use in the more elaborate displays, like the building’s carefully preserved courtroom — where some of the most important hearings actually took place — turned into a 3D cacophony of lights and sounds.

The museum is just as dedicated to cops as much as the robbers. I mentioned comic books before: They actually have their own corner. It’s small, like my happiness, but there. In case you didn’t stay awake through J. Edgar, comic books were among the federal government’s biggest PR platforms, serving up stories of heroic lawmen to inspire kids against the criminal lifestyle. Though admirable, it’s also treading scary propaganda territory.

In the end, the museum’s messages come mixed when you hit the gift shop.

This is where Las Vegas feels very fitting for the Mob Museum. Upon exiting the museum — in one of the final displays, visitors can leave a recorded story with optional identity concealment to tell their stories about how the mob affected them — you’re in the souvenir shop. Load up on costume fedoras, shot glasses, specialty barbecue sauces, kids books, and other knickknacks.

Inside the Mob Museum's gift shop. Note the children's books, which I guess are fun. Taken from my iPhone.

This would be fine, if it weren’t for the last two hours I spent mulling over the ultimate price people paid that informed this history. It’s difficult to compromise between exhibits like the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre wall — with accurate blood splatters — to a gift shop that unironically sells “I ❤ Bad Boys” cozies and mock Godfather t-shirts and, this is true, Breaking Bad action figures.

Honestly, it’s fine. It’s a museum. A non-profit runs it and needs to keep the lights on, which I hope it does. There’s a lot to learn in these two hours, taking in the glamour, as well as the grit of an era long gone but whose ghosts remain. Another one of the museum’s final exhibits outlines organized crime as it is today, and how it continues to exploit people for profit around the world. This is why I thought Marvel’s Daredevil on Netflix was so gratifying: His first fight in the show was stopping human traffickers.

The museum does an excellent job at explaining the human cost of exploitation. I just wish it didn’t come with its own history.